Library of Congress Control Number: 2017930503

ISBN: 978-1-63045-038-0

Anticipated Publication Date: April 24,, 2017

Cover Illustration by Mikayla Lewis

About the reviewer:

Emily Vogel is the poetry editor of Ragazine.CC. You can read more about her in “About Us.”

Womb

by Eric D. Goodman

A Novel

Merge Publishing, 2017

$18.00, 375 pages

ISBN: 978-0-9904432-9-2

Where Material Becomes Immaterial

Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

Eric Goodman’s thought-provoking new novel, Womb, is more a novel of ideas than characters. The characters, indeed, often seem purposely to represent types, almost like the characters in Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, though the story is more realistic and less allegorical. There’s the unborn fetus, who narrates the story but does not have a name (until the very end), Mom, Dad, Brother. Mom and Dad do have distinct lives and personal issues, to which we can relate, but to the unborn embryo narrator (and thus to us, the readers) they represent the archetypal parents; they have personalities, yes, but it is their relationship to the narrator that matters.

The premise of the novel is that the unnamed consciousness, at first neither female nor male though gradually identifying as male, is connected to the Oversoul, cosmic consciousness, the oneness of being, and already partakes of absolute wisdom. Without getting into tricky metaphysical arguments about karma or metempsychosis, the narrator simply states the case, and the reader accepts it. A clever and seasoned storyteller, Goodman is careful not to plead a case, to make an argument, and by and large we simply accept the premise – though how the narrator has access to book knowledge continues to perplex this reviewer!

But the premise is also backed up with references to Plato and other thinkers, so that while we “know” this is a work of fiction, we accept the plausibility.

The child’s conception is the ultimate source of the complications of the plot – an unplanned pregnancy, first of all, and while the option of abortion comes up over and over again, this is not a pro-life versus pro-choice polemic. In fact, there’s implicit humor in the narrator’s reactions to his mother’s (and father’s) indecisiveness about ending the pregnancy, as in a drama where somebody who is concealed overhears his fate being discussed. It’s as if he uses body English to persuade her otherwise – indeed, the narrator sees his mission as influencing his parents, to improve their lives.

When she consults her doctor, Penny asks about a morning-after pill, but the doctor tells her it’s too late for that. “The pregnancy is too far along. It’s an abortion or birth. Something you need to consider seriously.” And when Penny says she’ll “think it over,” the baby urges, But don’t overthink it, Mom. Feel your decision. Feel me. You can hear the urgency! In another context this might be comic.

Next, it turns out that the biological father is not Penny’s husband (though the narrator continues to think of Jack as his Dad, even after the revelation). This storyline involves us in Penny’s dreary career as a sales rep for a drug company. Sartre’s famous dictum, Hell is other people, comes to mind as we watch her interact with the boss and the other workers. (“She feels trapped in her deadend job,” the narrator inside her observes.) Pure demoralizing hell. The mystery of the biological father is part of this.

Later, even further complications occur, but I don’t want to give away too many of the surprises. Suffice it to say that the unexpected challenges are just like real life, a mixture of tragedy and optimism. Through it all, the character the narrator refers to as Dad, Jack, a career counselor by profession, demonstrates over and over again how to respond to life’s curveballs with dignity and aplomb.

Like Goodman’s earlier novel, Trains, Womb is a Baltimore story, though, given the point-of-view of the unborn narrator, this is not quite as crucial. Still, scenes from Federal Hill, Towson and elsewhere give a flavor to events. Penny’s and Jack’s struggles could happen in no other place to feel at once so homey and so anonymous. Penny’s mother died in childbirth, and her father was never there when it counted. Jack, indeed, is her bedrock, his heroism of the quiet kind.

The narrator meanwhile desperately wants to hold on to his connection with the cosmic overview, knowing that life is fleeting and the best one can do is try to enjoy it. This is something he knows. But by novel’s end, when the baby is born, he begins to lose the purity of his understanding as life’s compromises become real, and he begins to get lost in the particularity of the decisions we have to make, in time, decisions which in turn provoke more decisions, and life just goes on.

So, as a novel of ideas, what exactly is the overarching idea here? The answer lies in the epigraphs Goodman has chosen. From Billy Collins: “All babies are born with a knowledge of poetry, because the lub-dub of the mother’s heart is in iambic pentameter. Life slowly starts to choke the poetry out of us.” From Henry David Thoreau: “I have always been regretting that I was not as wise as the day I was born.” Or, as we learn from the Tao te ching, the farther you go, the less you know.

Womb is an entertaining, provocative read that stays with the reader after he puts the book down.

About the reviewer:

Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore, where he lives, and edits The Potomac, an online literary journal – http://thepotomacjournal.com . His latest book is a collection of poems called Mata Hari: Eye of the Day (Apprentice House, Loyola University), and another poetry collection, American Zeitgeist, is forthcoming from Apprentice House later this year.

Far from Nothing

by Zoltán Böszörményi

The Extraordinary Ordinary

Reviewed by Roberta Crawford Morency

. . . And yet, every time I turn my attention to things I can clearly comprehend—at least in my opinion—they convince me of their verity with such force that I find myself saying: let him, who is capable of it, deceive me, but he will never negate my existence so long as I think I exist; and neither can he erase my past existence, if my existence has once been established as a fact . . .

~René Descartes

Romanian born, the author emigrated to Canada where he received a degree in philosophy at Toronto’s York University. Now a resident of Monaco, Boszorenyi writes his story in first person displaying his life as sales manager in an auto dealership.

Married, with a young son, he feels no guilt about his first extramarital affair.

“I tell myself that in Wanda’s hands I was a helpless victim of seduction.” He later faces the realization that he is being unfair to both women.

The author’s prose is filled with poetry: “A voice of despair opens a wound in my soul.”

Ultimately, Boszorenyi shows the reader an ordinary life working with other car salesmen in the dealership. What keeps you turning pages are his humorous thoughts about relationships with co-workers and subtle philosophical comments, not to overlook his admirable writing style.

This is a book you’ll enjoy.

About the reviewer:

Roberta Crawford Morency‘s career was in radio, television and newspapers. Doctors had mistreated her anemia by prescribing iron, which almost led to her death. She recovered health by donating a full unit of blood at the blood bank weekly for three years. In 1980, she founded Iron Overload Diseases Association, Inc., after researching the condition. She discovered that millions of American’s lives are shortened by iron oxidizing in storage sites, causing any and every deadly, expensive disease. Her other two books, praised as life-saving information, are “The Iron Elephant,” nonfiction, and a novel, “tick, tick, tick,” which is also written as a screenplay. Her latest is the sci-fi novel, “2095.”

what if i got down on my knees?

by Tony Rauch

No Pretending

Reviewed by Marilyn J. Baszczynski

Imagine sitting at the local bar, minding your own business, when a strange man comes in, sits down next to you, and starts talking. His voice is easy to listen to, not too loud, sometimes melodic. You take notice, entranced, hang on his every word as he weaves his stories—some weirdly personal, others just wildly weird or comical—but you want to believe every one. This is how the reader experiences Tony Rauch’s latest collection of short stories, “what if i got down on my knees?” The subtitle, “romantic misadventures and entanglements,” merely hints at the roller coaster ride through bizarro worlds ahead.

The book comprises twenty-one stories/sketches grouped into four sections or parts: “please don’t go,” “even just for a little while,” “gusts in the alley” and “shiny things.” Within each section, stories are loosely connected, somewhat relatable through deeper underlying themes.

The stories in “please don’t go” revolve around loss, unrealized potential and loneliness with a fresh and quirky approach. Among them, two unemployed men run herds of dogs through town, teens go into a basement to get depressed, a ball player misses out on life and a blind date with a fetish-porn photographer turns catastrophic. The language is engaging, with nuanced leitmotivs of unending or impossible journeys, emotional stagnation and detailed imaginings of how things might have been and weren’t.

My favorite section, “even just for a little while,” takes the reader deeper into angst-ridden territory. From the absurdity of a tiny baby pulled out of a lump in a man’s side, the reader shifts to a young boy finding out about his father’s secret family. Then the enticing possibilities presented by “the new neighbors” are explored by a protagonist/writer who allows Rauch a complicit nod to his readers; when asked about what he writes, the protagonist suggests, “mostly three page mood pieces,” then later admits, “A lot of austere, expressionistic stuff. But none a that self-pitying crap that’s so popular. […] I don’t really consider them stories or anything, they’re more like I’m pretending…Pretends.” Then finally he considers, “Ah, to just be honest, I guess. To report what I see, what I feel.” Yes…

Here lies an intriguing aspect of these stories or “pretends”—so much of what Rauch writes strikes a compelling emotional chord. The reader inevitably empathizes with the protagonist’s desire to emerge from the garbage of past mistakes, to grow newer and better and to overcome the fear of change. Rauch aptly explores the loneliness of an outsider watching life whiz past the bus window while stuck sitting in the back.

The stories in “gusts in the wind” examine some interesting takes on nostalgia and regret while those in the last section, “shiny things,” seem to imply a call to action. The childhood victim-turned-concrete magnate exacts a concrete-filled revenge on his former bullies. The young man mourning the loss of a friend invites a girl at some party to attend the funeral with him; she reminds him, “Maybe it’s a good thing to break away from your past, in order to find your future.” Rauch, however, doesn’t seem to like tidy groupings or endings; he remains hopeful about future possibilities with his final stories, “how i hope to die” and “shiny things.” He leaves his reader intrigued.

With its unorthodox style ranging from anecdotal to stream-of-consciousness, simple to complex structures, from the lyrical to the hysterical and often unconventional language, “what if i got down on my knees” is one of the most unique, surprising and creative collections of short stories I have come across. A refreshing must-read.

Tony Rauch has four short story collections published. In the past he has been interviewed by the Prague Post, the Oxford University student paper in England, Rain Taxi, and has been reviewed by the University of Cambridge paper, MIT paper, Georgetown University paper, Iowa State paper, and the Savanna College of Art and Design paper, among many other publications.

Info and samples on “what if I got down on my knees?” can be found at https://trauch.wordpress.com/books/whatifigotdown/

The Girls in the Chartreuse Jackets

The Girls in the Chartreuse Jackets

by Maria Mazziotti Gillan

Cat in the Sun Books

Binghamton, NY

ISBN: 978-0-9911523-22

$18.00

The Last Word Is “Grateful”

by Eniko Vaghy

A former teacher once told me that it is not the first word of a poetry collection that matters but the last. In The Girls in the Chartreuse Jackets, poet Maria Mazziotti Gillan concludes with the word “grateful,” thus unveiling the hidden message of this wonderful collection. Maria Mazziotti Gillan does not use gratitude as a “catch-all” word for a series of emotions, but unwraps gratitude and places every aspect of it before her reader, giving it a newfound significance and distinct voice. The type of gratitude presented in The Girls in the Chartreuse Jackets is not a static sensation – it is neither overly exuberant nor strictly somber (though both extremes arise). I would say it is akin to falling on your back and getting the wind knocked out of your lungs. You lie paralyzed – simultaneously afraid and in awe as oxygen slowly fills your chest and leaves you thankful for the air, but oddly nostalgic for that uncomfortable suspension of body and breath.

Gillan gives her readers this kind of punch and release with her poems of gratitude. In “How the Dead Return,” Gillan is concerned with two losses, the passing of her mother and the tragic decline of her husband’s health. Gillan begins despondent, administering a tender nudge to the reader’s gut:

Ma, sometimes I feel that you are with me / each day, though you’ve been dead eighteen years already, my life / slipping away from me like water / in my hands. Why is it that you are the one I think of always / when I am afraid or tired… (Gillan).

In the next stanza, Gillan seems to revive a little, explaining that her mother’s voice encourages her to persevere even when the desire to “…crawl / into [her] bed to hide” (Gillan) is acute. But this strength is immediately obliterated when Gillan sees her husband, Dennis, “…sliding down / in his electric wheelchair, his head bent / like the broken stalk of a tiger lily / or a gladiola, eyes terrified and pleading” (Gillan). This is the breathless moment of the poem. The audience is given this image of a man who is as precious as a flower to his wife, but has been trampled over and destroyed by disease. When Gillan states, “…I am tired of so many people who need me, / no one for me to turn to for comfort…” (Gillan) the poem becomes increasingly claustrophobic and the reader starts to wonder if any reprieve will be reached.

The tension in the poem is cut with one word, or should I say person – “Ma.” Gillan writes:

…Ma…you come to me / as though you were still alive. Sometimes, / I can smell you, vanilla and flour and sugar, / you with your bread dough rising in its bowl, / you bringing me dishes of pasta or cups of espresso… (Gillan).

By including these sensory details such as the scent of Gillan’s mother’s cooking and the types of comfort food she brings, Gillan releases her readers from their state of limbo. With these five lines, the reader is able to resume, to live once more. The true resolution is achieved when Gillan ends her poem by saying: “I swear I can close my eyes and conjure you up, / and for a moment, it’s your arms I feel around me, / your hands in my hair” (Gillan).

And we are back. This final passage is the epitome of the summit of gratitude; the glorious inhale. Its flavor lingers on the reader’s palate; it stings like a fresh scab. Gillan reveals that gratitude is not achieved through primarily good experiences or acknowledged in the midst of moments of pleasure. No, gratitude arises in lieu of something. The fact that Gillan can relish the cooking and tenderness of her mother is because she is not physically present and will never be again. This does not dilute Gillan’s emotions, though. To her, eternity is possible for those who wish to remember and it is through the memories of another person that one can receive comfort, and thus, gratitude.

About the reviewer:

Eniko Vaghy is a senior at SUNY Binghamton majoring in English Literature with concentrations in Creative Writing and Global Culture. When she is not writing poetry or reviews, you can find her exploring the beauty of her hometown with all the zeal of a first-time tourist.

Eniko Vaghy is a senior at SUNY Binghamton majoring in English Literature with concentrations in Creative Writing and Global Culture. When she is not writing poetry or reviews, you can find her exploring the beauty of her hometown with all the zeal of a first-time tourist.

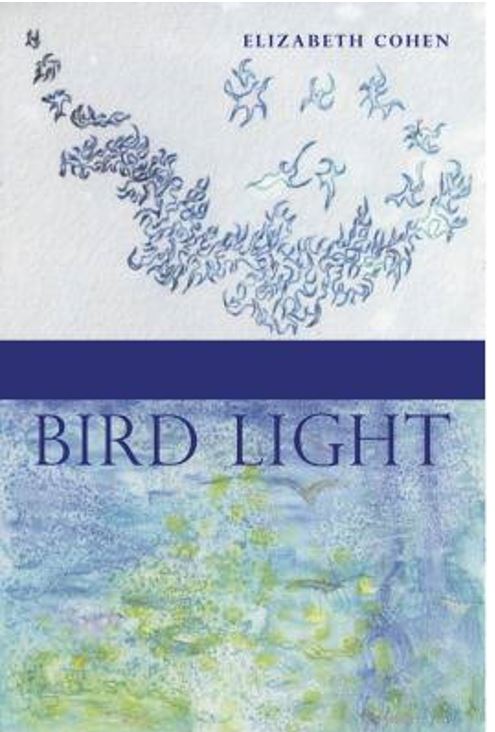

follow language to its roots

and find birds

perched on their nouns

like the stuffed birds

at the Museum of Natural History

wearing their root clothes

and elaborate root hats

full of the ancient taste

words have when pressed

to the tongue

I believe much thought and preparation has been spent on every element of this book. The gorgeous illustrations, by artist and writer, Aliki Barnstone, fit perfectly with the introduction of new sections. And Cohen’s section titles are a work of beauty in themselves.

From Habitat to Murmuration, from Field Marks to Migration, ending with Identifiable Markings, Cohen’s naming, her phenomenology, guides the reader through variations and stages of life. Interspersed with a sincere hope or desire for belief, leavened with an understanding of nature’s laws, and always observing, while writing new narratives, BIRD LIGHT becomes a guide to life. Birds, long with us, long observers of the human race, watch back from Cohen’s smart pages. They guide us as we guide them.

I strongly recommend this poetry collection, for I believe it has the potential to become one of those that find a place on one’s bookshelf —between the “Sibley’s Guide to Birds” and one’s binoculars—where BIRD LIGHT will serve as a touchstone for recalibration.

About the reviewer:

Lucy M. Logsdon resides in Southern Illinois where she raises chickens, ducks and other occasional creatures with her husband and two rebel step-grrrls. Her many works have appeared or are forthcoming in a variety of places, including: Nimrod, Heron Tree, Poet Lore, Crack the Spine, Literary Orphans, Pure Slush, Publisher’s Weekly, Seventeen, Talking Writing and Drafthorse. She received her MFA from Columbia University).

Show Time at the Ministry of Lost Causes

by Cheryl Dumesnil

The Seed of Tragedy is Just a Beginning

Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

In his famous “Ode on Melancholy,” John Keats enjoins the reader to “glut thy sorrow on a morning rose” when sadness is about to overwhelm you. The morning rose’s fragile bloom dies so quickly, and happiness is so fleeting, but this is where it’s found, in the odd bits of nature and life that pass us by. Further on Keats expands this thought:

Cheryl Dumesnil’s poetry makes me think of this. Not only does her work abound in images and scenes from nature, images as emblematic as they are realistic, but it has this sense of negative capability wherein the seed of tragedy is always at the heart of the things we value and cherish, or, as Dumesnil puts it in “Breaking the Broken Things,” when considering the implicit ache at the core of tenderness:

Indeed, the first of five sections into which the collection is divided is called “Good Morning Heartache,” with a poem by the same name, after the Billie Holiday song. The poet is just waking up.

And later in the poem:

Or again, as she writes in “The Acrobats of Pittsburgh,” having left her family to travel across the country:

Why does anyone ever leave anyone they love?

Time is so fleeting, why ever separate yourself from those that make you happiest? The narrator is on the phone talking to her children three thousand miles away. It’s a rather lengthy, complex poem which also includes allusions to an accident that has hospitalized her father, likewise back home in California, and a flock of Pittsburgh pigeons, constantly disrupted but oh so resilient, graceful. The poem begins:

And it ends some seventy-odd lines later:

The aching beauty in the evanescent is so succinctly captured in “Notes to Myself on the Morning after His Birth,” when, noting various aspects of the newborn, she writes “you will / never get that back. Nor will it ever // leave you.” Ah, that asshole life, that unconscionable purveyor of loss, is up to its old tricks again.

And that’s at the core of these poems, really, the quotidian disasters – divorce, illness, common as mud – and yet the resilience, the impulse to regroup, move forward, persist, endure. What’s so lovely about Dumesnil’s poetry is not just the inventiveness with language, the vivid images, but a kind of “attitude” that suffuses the work, partaking in a kind of wisdom, captured so concisely in her epigraph from Lao Tzu: “Do you have the patience to wait till your mud settles and the water is clear?” Dumesnil is patient indeed and sees right to the bottom of the pond.

Some of Dumesnil’s poems indeed have a subtle, good-natured humor in their wry observation of the fleeting details of life, the moments that slip past before we can hold onto them long. Some examples are the charming “Tampons: A Memoir,” “Love Song for the Drag Queen at Little Orphan Andy’s” (though this one does involve heartbreak), “Ode to Pink Floyd,” “On Air Guitar, Lip Gloss, and Flat Irons,” and the touching poem about her son titled, “Melodrama of the Suburban Kindergartener,” chronicling that moment when the brave little tyke, like a fledgling leaving the nest, walks across the “flat acre of asphalt, to his classroom,” all by himself, “molasses pace and sobbing.” Dumensil continues: “This is where // survival begins: that boy finally crossing / his threshold, this mom letting him go.”

As John Keats might advise, “No, no, go not to Lethe …” but glut thy sorrow on a small boy crossing the asphalt into the rest of his life.

About the reviewer:

Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore, where he lives, and edits The Potomac, an online literary journal – http://thepotomacjournal.com . His photographs, poetry and fiction have appeared in many literary journals. His latest book is a collection of poems called Mata Hari: Eye of the Day (Apprentice House, Loyola University), and another poetry collection, American Zeitgeist, is forthcoming from Apprentice House.

The Darling of Kandahar

By Felicia Mihali

The Darling of the Kandahar

Review Dr Mirella Vadean

A great novel to be read, to be held, but mostly to be recreated at a very personal scale

(Tomas, Guard Duty)

First published in English in 2012, the novel The Darling of Kandahar was launched in French on October 27 in Montreal, in the author’s own translation.

The story tells a romance that starts “by chance”. The picture of a beautiful young woman on the cover of a Canadian magazine catches the eye of a soldier fighting in Afghanistan.

From the beginning we are moving to and fro between words and images, trying to deal with the simulacra of our lives. What is fiction and what is reality in all this? Has the war become affective capital nowadays? How can we possibly understand ourselves anymore while living all together in a specific community or in a very eclectic one?

Felicia Mihali wrote a story based on a real event not in order to provide us any answer but to raise some fundamental questions especially about our individual identity as opposed to our public one.

The novel’s main theme is the quest for one’s identity beyond any ethnic, cultural, territorial or personal boarders. This quest is wisely placed in a contrasting, polarizing space caught between a Middle-East war on one side, and a peaceful society on the other. The two characters evolve between these two poles trying to understand themselves and their values at the deepest level. All along this voyage we need to abandon what we knew about ourselves, we need to leave behind the old, socially manufactured identity in order to embrace other people’s self:

“When you are a soldier, this question doesn’t exist anymore. Being a soldier is an identity in itself, and the war is his identity, a transnational identity” (p. 86)

It’s only chance that brought together Irina and Yannis, two young people who seem to have nothing in common. As a soldier in a very distant and senseless war, Yannis is confronted on a daily basis with the fragility of life. One day, “from his check point” he sees the picture of a beautiful young woman as a graduate, on the cover of a review ranking the Canadian universities. Afterwards, through a series of e-mails, Yannis comes in contact with that striking girl who leads a very casual existence under the anonymity of the urban routine.

As the novel moves forward, the force of this contrast between the two characters leads the reader to new reflections. What are the things that keep our hope alive, that makes us keep struggling for more in life? This is what the characters never ask aloud but this secretly guides readers to constantly question themselves. This very contrast between Irina and Yannis shows us what people want and what they don’t, who they are and who they intend to be. Without contrast in our lives, we would be condemned to a utopian existence. Without a different perspective to challenge us, we would be left without impetus to stretch our own thinking.

Yannis is the first one to experience this feeling of being subjected to the metamorphosis caused by the war he was waging in a foreign land. As for Irina, she discovers this new contrasting dimension that life grants her once her electronic “rendez-vous” with Yannis starts up. Consequently, readers too begin to measure the distance between the reality and its very representation.

Felicia Mihali knows how to play with her readers, how to entice them deep down into the maze of her world. For this novel, she conceives a very ingenious, two-side framework including Irina, the one who speaks throughout the entire novel, and the reader to whom Irina tells the story. In no time, the reader becomes a sort of Irina’s Other, the collective character to whom her testimony and her confidences are addressed. Irina needs this trusting and quiet confident as much as she needs Yannis’ letters. Amazed and puzzled, we follow her along, step by step.

From the narrator’s point of view, Irina serves also an additional purpose: she’s not only revealing the story of her life; she is telling us a story that belongs to History and that is a part of it. The Darling of Kandahar reflects the modern world in the light of the lost grandeur of great wars such the one led by Alexander the Great; it tells us of the founding of Montreal by Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve and Jeanne Mance. Finally, it displays the lost mythical paradise of Afghanistan, from what was before a Thousand and One Nights, now turned into the haunted place of a Thousand and One Nightmares.

Despite all those historical events that continue to reverberate in our modern world, what remains foremost in our mind is a beautiful love story. Too hesitant, Irina misses the opportunity to acknowledge her love to Yannis, dying too soon on his mission. When it is too late already, Irina realizes how fragile life is and what people should stand for.

“When you are alone, you think a lot about death, and this is dangerous. Fear transforms us into odious people, badly behaved. I think we should live in sweet ignorance of death. The good part, though, is that faced with danger, people ask themselves more often if they are happy” (p. 101)

With this new novel, Felicia Mihali confirms that we are born to be, yes it’s true, but mainly we come into this world with the intention to be, to create our own life, in spite of all prejudices and stereotypes. At that point, we can fully discover ourselves even though sometimes we need to trade the ordinary against the extra-ordinary.

The university rankings, the war in Afghanistan, Yannis’s death in a dusty desert on the other side of the planet, none of this should be the call required to awaken one from inertia. We don’t need competitions, wars, deaths to be able to discover who we really are. However, life should get us ready to deal with all kind of events while remaining true to ourselves.

What Irina accomplished in the end, was to find her own self, somebody capable of love and devotion. As for the readers, they too should be careful not to miss their chances before it is too late. The Darling of Kandahar offers such a wonderful opportunity.

A great novel to be read, to be held, but mostly to be recreated at a very personal scale …

About the reviewer:

Dr. Mirella Vadean has an interdisciplinary Ph. D. in Theory of the imaginary (literature, philosophy and music). She was professor of French and Francophone Literature at Concordia University in Montreal for 10 years. She is the author of several articles and collective works, in peer reviews. She specializes now in administration and continues her research on the topic of the altruistic gift, both from social and philanthropic perspectives.

Recent Comments