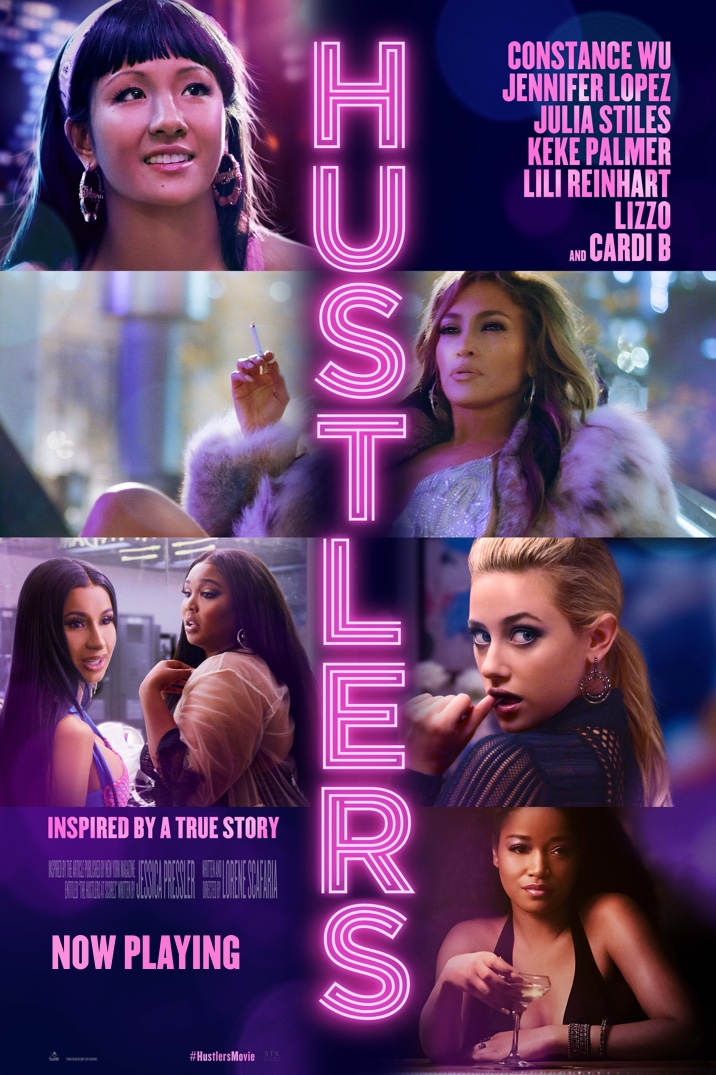

Photo credit: STXENTERTAINMENT.COM

Scene from Hustlers

In Hustlers, Women Tell the Story

by Margot Parmenter

Film Reviewer

With Hustlers, writer-director Lorene Scafaria manages to make a story about a gang of strippers who drug and defraud men into a metaphor for what it means to come of age as a woman. Like a proverbial stripper with a heart of gold, the resultant, Scorsese-inspired crime drama contains a deeper message about female consciousness and friendship — one that is all the more moving for its unexpected mode of delivery.

The film’s first act is a piquant period piece set in New York City circa 2007, in the era of unabashed excess before 2008’s stock market crash. Destiny, a babe-in-the-woods from Queens (Constance Wu), arrives on the high-end strip-club scene determined to support her elderly grandmother but naïve about the industry’s power dynamics. Thankfully, a mentor soon materializes in the form of veteran dancer Ramona (a magnetically commanding Jennifer Lopez), whose first on-screen appearance is a mind-blowing number that ends with her dripping in singles, waltzing off the stage to a standing ovation. She takes Destiny under her wing—or, as in an early scene between them, into the literal bosom of her fur coat—and the two become inseparable.

The film’s first act is a piquant period piece set in New York City circa 2007, in the era of unabashed excess before 2008’s stock market crash. Destiny, a babe-in-the-woods from Queens (Constance Wu), arrives on the high-end strip-club scene determined to support her elderly grandmother but naïve about the industry’s power dynamics. Thankfully, a mentor soon materializes in the form of veteran dancer Ramona (a magnetically commanding Jennifer Lopez), whose first on-screen appearance is a mind-blowing number that ends with her dripping in singles, waltzing off the stage to a standing ovation. She takes Destiny under her wing—or, as in an early scene between them, into the literal bosom of her fur coat—and the two become inseparable.

At first, things are good: Destiny makes “more money than a brain surgeon,” bails her grandmother out of debt, and even has enough left over to splurge on an over-sized handbag (wardrobe designer Mitchell Travers’s re-creation of the period’s fashion, from the huge purses to the Juicy Couture tracksuits to the bejeweled Bebe t-shirts, is exquisite). Ramona draws up samples for “Swimona,” a ridiculously impractical, denim-based swimwear line she plans to launch. Awash in optimism and profligacy, the first third of the film is characterized by the kind of innocence that also inflects a young woman’s naiveté. Watching it, I was reminded of the college girl I used to be, so irrationally certain that sexism was dead and my horizons were unlimited.

But, as we know it must, the bubble bursts. Destiny leaves the club to become a mother, and when she returns a few years later, nothing is the same: there’s less money to go around, and an influx of imported talent has undercut prices and standards. After a particularly demeaning encounter with a patron, she reconnects with Ramona, who’s found a way to exploit the new market conditions: she “fishes” for rich men, hooking them in bars and delivering them to the clubs, where she gets a cut of what they spend. It’s a ploy initially delicious in its inversion of patriarchal power dynamics. But the promise is short-lived, and the women quickly find that their operation won’t scale. So, they decide to do what many a woman scrambling for purchase in a man’s world has done, albeit by more extreme measures — they hijack the system.

This scheme is the film’s second, and, from a crime-caper perspective, its most vivid act: along with former dancers Mercedes (Keke Palmer) and Annabelle (Lili Reinhart), Destiny and Ramona begin drugging their marks, spiking the men’s drinks with “just a sprinkle” of ketamine and MDMA. What follows flips the script on the all-too-familiar trope of the roofied female, to illuminating effect. In one scene, Mercedes sits in a private room at the club, debating what kind of chicken wings to order while a man sits incapacitated beside her, looking not so much endangered as neutralized. Although the film doesn’t diminish the women’s crimes, it’s hard to ignore the reality that their actions seem less sinister than the reverse scenario, in which sex substitutes for money.

Since any attempt a woman makes to co-opt a male power structure can only last so long, eventually the wheels come off, and the Amazonian fever dream that the gang enjoys at its height comes to an end. But the movie extends beyond the anticipated police bust, proceeding into a final act that foregrounds Ramona and Destiny’s friendship. There’s room to read this last act as a commentary on the second: as a proffered alternative for how to be a woman in a man’s world. In the end, the film leaves behind the hustle to focus on telling the women’s story, and I couldn’t help but think that this is what it means to arrive at mature female personhood — for women to cease trying to adapt the male narrative to fit our stories and instead to start telling them ourselves.

About the reviewer:

Margot Permenter is completing an MFA at the Savannah College of Art and Design. She works primarily in nonfiction.

Margot Permenter is completing an MFA at the Savannah College of Art and Design. She works primarily in nonfiction.

Recent Comments