***

A New Zimbabwe

A Christmas road trip through a land of contrasts

by James Collector and James Roditi

We picked up Renée, our seasoned 4×4 Toyota Prado in Lusaka, spent a day gathering supplies, and were on the road to Livingstone when we realized that we lacked enough Zambian Kwacha for the toll gates. At each town we passed, long lines stretched outside the banks and ATMs. It was two days before Christmas and people were withdrawing their paychecks. Together we made an odd pair, an American and an Englishman coincidentally both named James, pulling into shops and asking to change our U.S dollars.

No one could help us. We slipped through the first tollgate a few Kwacha short and continued on, concerned that we might have to backtrack, preventing our safe arrival before nightfall.

To our relief, we were informed in the next town that there were no more tollgates ahead. We turned up “Lazy Bones,” a 70s’ rock song by the Zambian band, Witch, and sped down the potholed road to Livingstone, our first destination of a 3,500-km road trip out of Zambia and around Zimbabwe. Sacrificing holidays at home for adventure, our timely journey would take us through many sites of cultural and economic significance for Zimbabwe, which had only several weeks ago overthrown its 37-year dictator, Robert Mugabe, in a graceful coup.

Given the political shift, our holiday was now overshadowed by curiosity: What would Zimbabwe be like without Mugabe? We resolved to ask Zimbabweans what they thought their future held under the new leadership of Emmerson Mnangagwa, aka ‘The Crocodile.

♦

Victoria Falls

In Livingstone, we met a representative for Bundu Adventures who informed us our three-day rafting trip on the Zambezi was all set for tomorrow, Christmas Eve. The next morning, we set off from directly below the 300-feet high Victoria Falls. One of the Seven Natural Wonders of the World, the mile-wide falls known locally as ‘Mosi-Oa-Tunya’—the smoke that thunders.

After the first day of rafting 23 class-four and five whitewater rapids, we pitched camp on a sandy beach in Batoka Gorge. James Collector stood at the turgid river’s edge looking across to the black basalt cliffs of Zimbabwe, bright green with new growth brought on by seasonal rains. He’d never been to Africa, let alone Zimbabwe, a country that had transformed from the 1980s breadbasket of Southern Africa into a basket case—thanks to violent land occupations, the disintegration of the farming system, nationalization of industrial businesses, dramatic hyperinflation, and complete economic collapse. Yet in spite of this Zimbabwe’s beauty and potential was spoken of with reverence, even by our Zambian rafting crew.

Consisting of Captain Potato; chef Banda; supply rafter Stanley; support kayakers, Innocent and Clement; and trainee guides, Little Rasta and Ben Mapalanga (son of pioneer raft guide, Vincent Mapalanga), our seven-man crew represented the multi-generational livelihoods which depend on this section of the Zambezi River. With limited employment opportunities, they had no complaints about working on Christmas Day.

However, their livelihoods face a colossal threat. The proposed Batoka Gorge Hydro Power Project would flood the gorge up to 650 meters below Victoria Falls, submerging jobs along with many of the iconic rapids. Still in its planning phase, the 6-billion-dollar project would create employment during its construction, but for whom? A consortium of international companies would conduct the engineering, legal, environmental, financing, and construction processes in the short-term, after which the project would irrevocably change the natural scenery and way of life in the area. A renewed, economically stable Zimbabwe, increases the chances of this happening.

As porters from the nearby villages helped us carry our supplies out of the gorge, we gazed back down at the mighty Zambezi, where multi-day rafting trips like ours might soon be impossible.

Crossing the border into Zimbabwe a few days later proved hassle-free. After a restful night in the town of Victoria Falls, we were on the way to Hwange National Park the next morning, impressed by the quality of the roads in comparison to Zambia. The largest of Zimbabwe’s parks, Hwange is home to over 100 species of mammals and 400 species of birds. In five hours, we made our way through the dense bush to Sinamatella Camp, perched on an escarpment overlooking lush, green plains stretching to the horizon.

Sighting wildlife during the wet season can be a challenge. With water sources abundant and full foliage on the ubiquitous mopane trees, the animals spread out and remain hidden during the day. Driving around the labyrinth of rutted, dirt roads, we managed to see a few hippos, a lone elephant, and numerous birds. A walking tour with a ranger yielded us little more than a glimpse of a land tortoise.

By the third day, we showed up at the main camp thirsty and discouraged. We were sitting at the bar when Henry, a national park ranger, entered. We struck up a conversation and he suavely agreed to ‘make a plan,’ the Zimbabwean parlance for proactive problem-solving. He returned a short while later with another guide, Doozy. After a round of negotiations, they offered us a night safari—if we were willing to pay in cash. Twenty dollars a seat. In Zimbabwe everything is negotiable, as long as you have cash. That evening we saw herds of buffalo and elephants, more than the American, James Collector, had ever seen in his life. Twenty dollars for a life-long memory. As we drove away, a mother elephant trumpeted in the darkness.

♦

Bespattered with a thick coat of red mud from Hwange, our vehicle drew stares on the wide, Jacaranda-lined streets of Bulawayo. We checked into the Bulawayo Club, an anachronism of the bygone colonial age — white columned façade, a fountain in the courtyard, grandfather clocks in the carpeted stairwell, and a vast, mahogany bar empty but for portraits of white men, uniformly mustached. When we asked the concierge, Lampda, where to find a car wash and block ice for our cooler (many supermarkets were sold out), he eagerly volunteered to help, and had Renée clean within an hour, retaining his pristine clean shirt and slacks.

The deserted Club stands in stark contrast to the bustling city. It was the day before New Year’s Eve and the shops were crammed in anticipation of the party. Hawkers were selling fireworks in the streets. The money changers were out in force. A carnival for children had been set up on the main street. Laughing kids splashed in inflatable pools, bounced on trampolines, raced tricycles, and visited the single white man on the scene: a skinny, beardless Santa Claus seated between a statue of a zebra and lion.

En route to the supermarket, Lampda answered our questions about the new political leadership with cautious optimism.

“It’s good for business at the Bulwayo Club, but I think too early for other changes.”

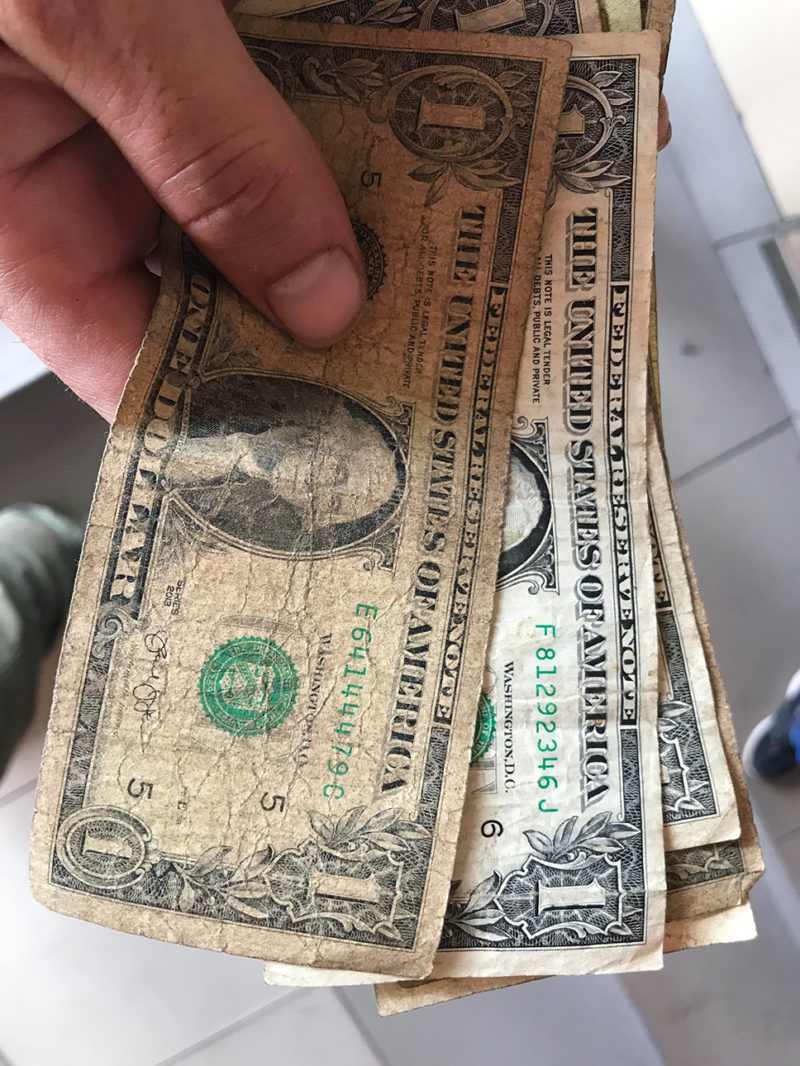

At the market, two men surreptitiously approached us in the checkout line and offered to pay our bill with their debit card in exchange for our cash. Following the hyperinflation of 2008, which rendered the Zimbabwean dollar valueless, the nation now operates almost entirely on U.S. dollars despite no official authorization to do so. As a result, cash is scarce. Dirty, worn dollar bills circulate alongside the clean Zimbabwean ‘bond notes,’ purportedly of equal value. We politely declined their offer, tipped Lampada for helping us find the ice, and drove half an hour south to Matobo National Park for sunset, sundowners chilling in our ice box.

At the market, two men surreptitiously approached us in the checkout line and offered to pay our bill with their debit card in exchange for our cash. Following the hyperinflation of 2008, which rendered the Zimbabwean dollar valueless, the nation now operates almost entirely on U.S. dollars despite no official authorization to do so. As a result, cash is scarce. Dirty, worn dollar bills circulate alongside the clean Zimbabwean ‘bond notes,’ purportedly of equal value. We politely declined their offer, tipped Lampada for helping us find the ice, and drove half an hour south to Matobo National Park for sunset, sundowners chilling in our ice box.

♦

Cecil Rhodes thought the majestic granite kopjes of the Matobo Hills a suitable place for a man of his stature to be buried. Astonishing views atop a rounded promontory known as ‘World’s View’ set a dramatic backdrop for the 3×1-meter brass plaque which reads: ‘Here lie the remains of Cecil Rhodes’—all that is left of the man in the country which once bore his name, Rhodesia.

James and James at Great Zimbabwe, a UNESCO cultural heritage site

Long before it bore Cecil Rhodes’ name, Zimbabwe was home to one of Southern Africa’s most prosperous ancient civilizations. Trade routes from as far as Asia crossed at an epicenter known today as Great Zimbabwe, a UNESCO cultural heritage site from which the country now takes its name: Zimbabwe – House of Stone in Shona. The massive stone ruins rival any of the world’s premier archaeological sites. Founded by ancestors of the Bantu and Shona people, the 800-hectare city thrived at its economic zenith between the 12th and 15th Centuries when it served as a trade link for cattle, beads, cloth, gold, and ivory.

Arriving on the last day of 2017, we found the monument clean and accessible as our young tour guide, Gift, led us through the rounded architecture and mysterious aura of The Great Enclosure. In that ancient place, Gift answered our questions with surprising frankness. He admitted he is active on Facebook, listed where he gets his news (Al Jazeera, Reuters, Twitter), and described the sudden shift in freedom of expression for Zimbabweans. Just months before, no one would speak their minds in public for fear of retribution by Mugabe’s secret police.

“The Crocodile gave us our democracy back,” Gift said. “And for that we must be grateful.”

At the end of the tour, Gift led us into a small museum where Mnangagwa’s portrait already adorns the reception hall. In the back room, eight soapstone eagle statues—believed to symbolize each of the ancient kings of Great Zimbabwe—stand on display beneath dim lights. The most prominent perches on a pedestal above a carving of a crocodile. One statue is a copy; the original remains at Rhodes’ estate in Cape Town. Legend has it that when the final eagle is returned to Zimbabwe, the country will once again return to peace and prosperity. Perhaps all they need is a crocodile.

It was New Year’s Eve. We left Great Zimbabwe and continued on to the Bvumba, a highland region studded with massive granite formations. With local musicians Leonard Dembo and Oliver Mutukudzi on heavy rotation in the stereo, we zipped along, windows down, enjoying the cooler air as the flat landscape began to contract, crack, and rise into mountains.

♦

We turn off the tarmac onto dirt roads through small villages. Passing families and other groups of people, we flash the ‘thumbs-up.’ Men and women of all ages return the gesture with enthusiasm—the spirit of the New Year seeming particularly poignant as the change in calendar year truly carries meaning this time.

By dusk, we arrive at the luxurious Leopard Rock Hotel. After cleaning up, we make it in time for the last serving of dinner. Older Zimbabwean families quietly eat their four-course meals, their children eyeing the dance floor. One table of young black Zimbabweans are already up dancing and laughing. “We are making this party alive!” one calls out.

We leave the pop music and walk past pictures of celebrity guests to the bar. There, we find a motley assortment of white Zimbabweans gravitating together around drink and memories. Once a prosperous jewel in Zimbabwe’s crown, complete with 18-hole golf course, a casino, flood-lit tennis courts, and stunning views into Mozambique, Leopard Rock is now a shadow of its former self. The violent land occupations of the 2000s, where war veterans were encouraged by then President Mugabe to seize the farms of thousands of white citizens, raised red flags for foreign investors and tourists alike.

As the clock struck midnight, we found ourselves deep in conversation with some white Zimbabweans returning from exile in Australia. They held themselves with a mixture of strength and disenfranchised frustration. Prone to lapses in speech—perhaps restraining themselves from speaking candidly—they nevertheless made excellent drinking companions. By two in the morning, we were playing snooker in the dilapidated casino. The red balls kept falling through a hole in the corner pocket and rolling across the burgundy and lizard-green carpet.

Bleary-eyed the next morning, we stopped for fuel and asked the station attendant his New Year’s Day opinion of the new leadership.

He replied with a shrug, “Same ma-kombi, different driver.”

♦

On a back road to the Eastern Highlands, our next destination, we paused to take photos of the green mountains ahead, laced with mist and waterfalls. An old woman carrying a large bundle approached us and, without any English, asked for a ride. She was going to the Honde Valley; so were we. She climbed in, clapping her hands in thanks. If not for us, she would have crowded into one of the many ma-kombis, mini-buses, that link the country together.

We dropped our passenger off in Hauna and continued on to Nyanga National Park where we planned to trek part of the Turaco Trail before linking up with a new route, the Hydro Trail, which no tourist had ever walked before. Our itinerary would lead us through pristine forests, down into the Pungwe Gorge, past three small hydroelectric projects, and conclude among the homesteads and small holdings surrounding the undulating green hills of the Eastern Highland’s Tea Estates.

An experienced Zimbabwean outdoorsman, Bernie Cragg, pioneered the Turaco Trail and, before embarking on the first leg, we met him at the headquarters of his company, Far and Wide. He and his wife provided us with a survey map, a cook stove, and some basic rations for the first two nights on the trail. Having spent decades guiding in the park, he suggests that we summit Mount Inyangani, Zimbabwe’s highest peak. We demure. Our professions in sustainable development compelled us to visit the Pungwe Hydro projects commissioned by Zimbabwean engineering firm, Nyangani Renewable Energy (NRE), who James Roditi worked for in 2014. It is NRE’s intention to link their newly established Hydro Trail to the Turaco Trail, thus creating a new route, which would exhibit their project on the national park’s periphery. Cragg is wary. NRE and Far & Wide have disagreed before, but eventually compromised.

Shortly after leaving Far and Wide on foot, our packs heavy with supplies, we turn left at a transmission line which links the hydro station to the national grid. It was the last we saw of civilization before entering the national park.

The views from the trail are spectacular. Beneath the high grass plateau surrounding Mount Inyangani, delicate waterfalls cascade over the escarpment into the Pungwe River, which flows out to the wide and fertile Honde Valley, and onto hazy plains stretching east into Mozambique.

That night in the Pungwe gorge, we were alone, camped in a densely wooded site next to a small set of waterfalls. The water was pristine, one could see the shimmering rocks through the surface, and drink it with your bare hands. Cool and sweet.

That night in the Pungwe gorge, we were alone, camped in a densely wooded site next to a small set of waterfalls. The water was pristine, one could see the shimmering rocks through the surface, and drink it with your bare hands. Cool and sweet.

Hiking along the river the next day, we talked about the importance of development for the region. James Collector’s experience as an ecological consultant had left him concerned about the modernizing impact of development, whereas James Roditi’s work in renewable energy had shown him that careful implementation of smaller projects could augment the local quality of life.

Collector: I can see why Far and Wide would be nervous about development here. It’s as beautiful as any place I’ve ever been.

Roditi: Yes, but the hydro development has been done on a small scale. The river remains the same upstream and downstream from the project. What’s more, you have a Zimbabwean designed, engineered, and constructed project that’s given employment and infrastructure to locals here.

Two days passed in the gorge before we saw signs of people: a cattle fence and fields of corn and bananas. The sun was setting as we walked along a dirt road with a view over the narrow canal where part of the river flows into the hydro project’s intake.

Roditi: This is a run-of-the-river project. Above the canal is a weir wall – not a dam wall – there’s no big flooded area above it. We won’t see it from here but it diverts the river into the canal along the valley’s contour before dropping it down that steep bank into the turbines. Then the water returns to the river, which resumes its natural course. The project doesn’t change the river; it just borrows its flow.

Collector: And so all of these farmers are here because of the hydro?

Roditi: Yes, the roads allow them to take their produce down to Hauna on ma-kombis. Avocados, bananas, yams, corn, mangoes, and tea. This area is very fertile.

Across the road two young boys, who had run out to see us hike past, waved nervously at us.

Collector: I wonder if I’m the first American they’ve ever seen, or if they even know what America is yet…

Small hydro station on the Chiteme river

Small hydro station on the Chiteme river

The third day, a local guide named Simba led us through high-mountain villages to a second small hydro station on the Chiteme river in the next valley over. As the first tourists to attempt the itinerary, we improvised a camp site near the river. In a classic scenario of ‘making a plan,’ Simba helped us obtain a few pieces of rusted rebar, which we cantilevered between two rocks over a small fire to make a rustic braai. Grilled chicken had never tasted so good. We needed it, as the fourth and final day’s walk took eight hours to traverse the vast tea estate and pick up our trusty ride, Renée.

While our rustic braai — a bar-b-que in Southern Africa — did the trick on the trail, two days later we grilled in style as guests of a white family in Zimbabwe’s capital, Harare. Our hosts (who requested to remain anonymous for safety reasons) represented two generations: a young couple in their 30s who had known no other President than Mugabe; and their elderly parents, who lived through the War of Liberation from 1964 to 1972. Plied with beer and scotch, the conversation took an inexorable turn into politics. With the kind of frankness that only a backyard braai can offer, we discussed The Crocodile and President Trump. Our host’s father supported Trump, since his remark that, if elected, he would depose Mugabe. For a family that had suffered under said dictator’s oppressive regime, the support seemed understandable. Nor was there any question of our hosts’ commitment to the country that they have called home since birth; each has persevered in businesses which generate employment and opportunity in Harare.

However, not all of our hosts agreed on Zimbabwe’s future. The most optimistic of them, the young father-to-be, believed that the previous degree of oppression could simply not resume and that any change would be an improvement. His father, the most cynical, expressed a view that Mugabe’s years of propaganda had produced a ‘lost generation’ without the work ethic or capacity to engage in democracy; a dictator was still necessary for governance. Yet, he claimed many of ‘salt of the earth’ citizens dislike the Crocodile.

The matriarch described a profoundly altered dynamic between white and black Zimbabweans in government.

“Previously we [blacks and white] could not publicly work together because supping with the whites was seen as treason. That barrier’s been lifted.”

Regardless of their differences, all our hosts agreed that they would vote for The Crocodile in the upcoming elections, now due to be held in May or June of this year.

The next morning, as we fueled up for our drive to Mana Pools, our final stop before returning to Zambia, we asked the gas station attendant his views of the new political leadership. The young man, who had a college degree replied;

“Working this job with my education, I was a joke, but now I can be optimistic.”

On the final long, dirt road leading into Mana Pools, we picked up a stranded employee of the park whose vehicle had broken down. It was our first chance to speak candidly to quasi-government official, who asked to be kept anonymous.

“Yes, it’s the same ma-kombi,” he agreed as we careened through puddles. “But not one driver, many drivers. And we hope that they have learnt from the previous one.”

We ended the trip as it started, on the waters of the Zambezi. After two days of watching elephants feed and hippos wallow on its banks, we left Mana Pools and crossed the river back into Zambia, touched with a note of melancholy. In twenty days we had visited seven national parks, met dozens of warm people, and had not been bothered once by police. Despite warnings of as many as 30 checkpoints on a single highway, we had driven 3,000 km without a single roadblock. A good start to change.

Within an hour of crossing over into Zambia, we were stopped for speeding while overtaking a struggling truck. Finally, our lack of Kwacha came back to haunt us. We paid the fine with the last of our cash, a $100 dollar bill. We were given no receipt and the policeman filed the money in his top pocket.

We found Zimbabwe to be a land of contrasts: highlands and plains, cities and bush, ancient sites and websites, wild rivers and hydro projects, blacks and whites, optimists and pessimists, opportunities and obstacles—despite them all, Zimbabweans will make a plan.

All images use with permission ©James Collector and James Roditi

CONTACTS

Bundu Adventures – +260 (0)213 324406 /

Bulawayo Club – +263 9 881964/5 /

Gift Tavapa, (tour guide at Great Zimbabwe) +263774116640 /

Leopard Rock Hotel – +263-772-100-790 /

About the authors:

James Roditi works in renewable energy development in Southern Africa. James Collector works as an ecological consultant in Northern California.

James Roditi works in renewable energy development in Southern Africa. James Collector works as an ecological consultant in Northern California.

Photos by James Roditi & James Collector.

A follow-up story will appear after the elections in Zimbabwe scheduled for the end of July. Stay tuned.

Recent Comments