TV Dinners

by Alfredo Franco

Thomas Black’s father left the family the summer before the Martin Luther King riots, when Thomas was five and they still lived in a real house in Virginia. He remembered the days leading up to his father’s departure. Thomas did not yet know what the word “divorce” meant. His father had purchased an enormous cardboard box in which to pack his belongings. Thomas dragged the box out to the backyard and turned it over, transforming it into a hideout. He invited three other neighborhood boys to join him inside. In the darkness, which was thick with the smell of cardboard and boyhood sweat, he whispered that his parents were getting a divorce. He had expected to impress the boys, but the meaning of the word was just as mysterious to them. There was a percussive boom as his father sent the box flying off over their heads with a kick. The sudden light blinded them. “Come inside, Tom,” his father commanded, blue eyes flickering with anger. His friends fled.

Now Tomás lived with his mother and grandmother in a modest rental complex in Adelphi, Maryland. His 75-year-old great-grandmother had also lived with them for a time: his mother had brought her up from Miami so that she would not die alone. His great-grandmother could no longer control her bowel movements, and the small two-bedroom apartment smelled of excrement. Tomás had seen the brown streaks on the bedsheets. He’d given up his room and slept on the living room couch. He would often wake to hear the heartbeat of the night, a closing door, a distant car, or his great-grandmother wailing in Spanish—ay, ay, ay, ay—and his mother trying to muffle her cries, for the neighbors downstairs were unforgiving. Lying there, he would imagine that he, too, had a cancerous lung until he was certain that his right lung was actually swelling and throbbing, as if a large splinter were lodged in it. Ay, ay, ay, ay, he wanted to cry out. On the day that his great-grandmother died, his mother and grandmother made him wait in the kitchen while the mortuary crew collected the body. But he peered through the holes of the pegboard partition that separated the kitchen from the living room. He saw two men with white peaked caps, white jackets, white surgical masks, and white rubber gloves, wheeling the shrunken bulk of his great-grandmother out of the narrow apartment on a stretcher.

“Lift up a little, Jack,” he heard one murmur through the mask. “More to the right…okay…straight…”

Almost a year had passed since his great-grandmother’s death, but Thomas could still smell feces. At least he had his own room back, though it was strange to think that someone had died in it. His mother and grandmother shared the other, larger room. Afternoons, the school bus would leave him on the corner of Hermes Way, a block from the apartment. He was in fifth grade and doing well, even enjoying sports for the first time in his life, thanks to the coach, Mr. McNair, a black ex-Marine sergeant fresh from Vietnam. Mr. McNair was hard on bullies, but encouraging to quiet boys like Thomas, to whom he taught boxing and football. After an initial fear of pain, Thomas became accustomed to the blow of the glove, and the sting and invigorating smell of the grainy calfskin football. Mr. McNair sent the boys on grueling runs around the school; Thomas would complete the laps faithfully, unlike many who sneaked breaks behind the parked school buses. “Okay, don’t run,” Mr. McNair warned the slackers. “But someday you’ll be runnin’ from a man and you’ll think of me”.

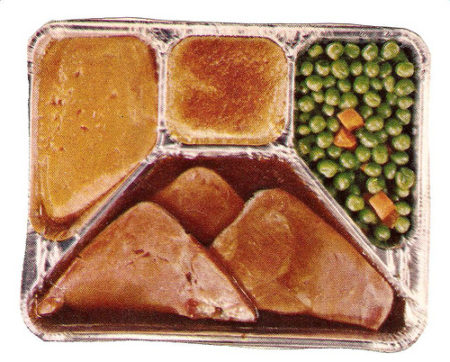

Thomas was usually ravenous when he got off the bus. He and Tíndara, his grandmother, would eat early in the cramped kitchen as soon as he got home. His mother was rarely home for dinner anymore. She worked as an accountant for the House of Kleen laundry chain and usually dined at the S&W Cafeteria with Mr. Funnell, a portly widower she had met at a church social. Tíndara stopped preparing the succulent, soporific Cuban meals of chicken and rice, black beans, and ropa vieja. Now she would simply heat up two Swanson TV dinners, most often turkey but sometimes, for a change, Salisbury steak. Thomas and Tíndara were invited to join Mr. Funnell and his mother for supper at the S&W one night. His grandmother, who had no English, kept looking nervously to her grandson to translate whatever Mr. Funnell said. His mother was embarrassed by this—how many times had she told Tíndara to take English classes at the local night school? Mr. Funnell was mesmerized by Tomás’s mother, who was not only much younger but dark, exotic, and fiery. When “Spanish Eyes” began to play over the cafeteria Muzak system, Mr. Funnell leaned over his meat loaf and mashed potatoes and said: “They’re playing our song, my chiquita cubana!”

One day in May, hungry though he was, Thomas did not go straight home but lingered in the burgeoning warmth with Chuck Fields and a couple of other boys from St. Tarcisius. An oscillating sprinkler watered the grass. Around them children of various ages, quickened by the spring, cavorted and shouted and swung from a jungle gym. When one of his textbooks slipped out of the green rubber book strap, Thomas bent over to pick it up. A sharp kick to his buttocks sent him sprawling, facedown, onto the sidewalk. Several children gathered round immediately, jeering, laughing. Thomas looked behind him. A boy of his age, whom he had never seen in the complex before, stood over him, making humping movements. Thomas rolled over and sprang to his feet. Chuck and the other boys withdrew into the crowd, frightened but relishing the spectacle.

The boy squaring off against him was slightly shorter, with rough-cut blond hair that went down over his ears and gave him a wild look. His blue eyes were cunning and focused, his thick upper lip curled in contempt. He wore a jean jacket and tennis shoes, making him more nimble than Tomás, who was still wearing his school tie, a V-neck sweater emblazoned with a heart and crucifix, and heavy brown shoes with thick soles and heels like built-up shoes.

“Whadda ya gonna do about it?” the boy in the jean jacket asked.

Thanks to Mr. McNair, Thomas was no longer weak; he had boxed boys larger than this several times at school. Yet his mouth was dry with inexplicable fear. The boy’s raw aggression paralyzed him. He wanted to speak but could not. The only word Tomás could think of was abuela. He cried it out within him, hoping that somehow Tíndara would hear and come to his rescue. He noticed an adult woman looking out upon the scene from one of the second-story windows. Tomás prayed she would lean out and diffuse the fight. She drew the curtain closed.

There was an expectant hush among the children, who had gathered into a tight ring. His friends were curious to see how Thomas would react. They were relieved that it was not their turn to be tested.

“Use what you know,” Chuck shouted. He’d seen Thomas box skillfully in gym class. Chuck’s mother had told her son that cancer was contagious, forbidding him to visit Tomás while the great-grandmother had lived there.

As the blond boy stood before him, overly confident and therefore excessively open, Thomas could see several targets that would be easy to strike, just as Mr. McNair had taught him. A fast right to the sternum would finish the bout quickly. But Tomás could not make his body move. In an instant, he was on his back upon a patch of sodden grass, his arms pinned to either side, a pair of knees weighing down his chest. Tomás gazed up uncomprehendingly and sorrowfully at the boy, who was snarling, exposing his yellow teeth. Tomás could smell the gamy odor coming from between the blond boy’s legs. His attacker counted to ten, then stood, arms raised in victory.

The crowd of children, even Thomas’s friends, cheered the winner. Thomas rose shakily. He was crying against his will, as if something had been broken, though he felt no physical pain. An older girl, face red and contorted, shouted: “He can’t take it like a man!” The crowd dispersed, and neither Chuck nor his other friends came over to console him. Thomas gathered his books and walked home in a haze, blind to the dazzling day.

Tomás let himself into the apartment as silently as possible. He dropped his books in the living room on the ragged red sofa that had once been his bed and sat, stunned, at the kitchen table, without calling his grandmother or switching on the light. The windowless kitchen was the darkest room in the apartment, but today the bright spring light from the large living room window shone through the holes in the pegboards like hundreds of tiny glowing eyes. The birds twittering outside sounded like the taunting children who had witnessed his defeat.

He could hardly believe what had happened. In seconds, his world, his image of himself, had changed forever. An unbearable feeling of humiliation throbbed in his chest, but also a tardy fury, an impotent anger with nowhere to go except back into himself. Why hadn’t he thrown a single punch? He dreaded going to school tomorrow. Would Chuck and the other boys spread word of his cowardice? What would Mr. McNair say? Thomas wanted to die.

As a younger child, when his father still lived with them, Thomas remembered being capable of exhilarating aggression. Once, on the school bus to kindergarten, sitting as he always did next to a little girl named Kathleen, an older boy in the seat in front of them turned around and struck them across their faces repeatedly with a copy of Life rolled into a hard tube. The boy had a port-wine birth mark on his cheek and a brown mole in the white of his left eye. The safety patrols did not see the attack, or chose not to. Thomas and Kathleen arrived at school with bruised faces, but told no one of the attack. That evening he went and threw his arms around his father’s waist in a show of love while surreptitiously slipping his hand into his father’s pocket until he felt the rough stag handle of the folding knife. His father, distracted by his son’s spontaneous affection, did not notice the theft. The next morning, when the older boy turned to them with his rolled up magazine again, Thomas extracted the larger of the two blades of the knife with his thumb and aimed for the mole in the boy’s eye. A safety patrol jumped on him, and the bus driver, a rural, bony old man, slammed the brakes. Thomas was disarmed, and the knife handed over to his grandmother that afternoon.

“Your son brought this to school today,” the bus driver said, “but I ain’t gonna tell the sisters this time.”

“Niño!” his grandmother exclaimed. She had not understood the driver’s words, but the knife in her palm said everything. The older boy never troubled them again, and Thomas felt the wild joy of victory in combat. Kathleen let him hold her hand and even probe her buttery smooth skin just under the hem of her plaid skirt.

“Tomás, niño, is that you?” Tíndara called now from the bedroom, where she liked to sit and read. She kept a small library on her side of the room; it consisted of the few Spanish books she’d been able to find in used bookshops and thrift stores, using pocket money that her daughter deigned to give her now and then. She dreamed of rebuilding the ample library she’d had in Cuba. The names on the spines of the books—Rubén Darío, Miguel de Unamuno, Ortega y Gasset, José Enrique Rodó—were of poets and thinkers, about whom she liked to tell stories to her grandson. “Whenever Darío visited his homeland of Nicaragua,” she’d say, “children would cast rose petals before his feet.” With her eyes closed, she would recite Darío’s poem about the swan: The song of the swan is heard above the storms…

Once, inspired, Tomás stole a blank Royal Vernon Line marbled notebook from the school supply room and wrote POEMAS in block capitals on the cover with his Sheaffer school pen. I should have written POEMS, thought Thomas, and tried wiping out the A, managing only to smear the blue ink. Then he realized that he had no poems in any language to put into the notebook. He only knew that he wanted children to cast rose petals before his feet.

Tíndara was a short, heavyset woman of fifty but looked sixty. Her once jet-black hair had gone gray. She wore a cheap short-sleeved, flower-patterned blouse with red plastic buttons, and double-knit trousers from Kmart. The button over her stomach bulged and strained. Her eyes were dark and bulbous, always looking nervously about, like a rabbit’s or a frightened child’s. In America, she was permanently afraid, locking the doors and windows against crime and English. Though an educated woman, she had convinced herself that English was a barbarous, inferior language, unworthy of her to learn. And in every “Anglo-Saxon” man she saw a serial killer or a molester of children, un depravado. She had warned her daughter not to marry an American, and look how badly that marriage had ended. She felt sorry for her grandson, his Latin soul marred by the blood of a cold, brutal people. Thomas’s mother would laugh at such thoughts, saying they were ridiculous and ignorant, but they made Tomás feel doomed.

“Tomás?”

His grandmother stood at the entrance of the kitchen. He could not raise his face, heavy with shame.

“Si, abuela,” he murmured.

“I didn’t hear you arrive. Que te pasa?”

“Nothing…”

“Something’s wrong, niño. What happened?”

Finally, he looked up, forcing himself to smile.

“Nothing, abuela…I’m just hungry.”

She noticed broken grass blades stuck to the back of his sweater.

“Did you fall while playing?” she asked, brushing them off.

Thomas remained silent and bowed his head again.

She asked if he was ready for his te-ve deena.

“Sí,” Tomás responded, though he wasn’t hungry anymore. But it would keep his grandmother distracted.

rkee o salisberry?” she asked, rolling the Rs.

“I don’t care.”

Tíndara went to the refrigerator and took two Swanson frozen turkey meals from the icebox. She first had to preheat the oven to 425 degrees. The old white oven, mottled with rust and chipped enamel, began to emit odors of methane and grease, which smelled to Thomas like his own humiliated body.

“Did you have a good day en el colegio?”

“Sí.” But Thomas could feel his lower lip trembling and his face reddening again. If only she would stop speaking and leave me alone, he thought. Full of fury and pain, he wanted to hit, destroy, kill. He could not get the blond boy’s snarling mouth out of his mind, or the taunting children.

The pea-green phone on the kitchen wall rang suddenly. Thomas jumped in his chair. Tíndara looked at him with her wide-eyed, anxious expression.

“Answer,” she urged. She was always afraid of not understanding if spoken to in English. Thomas didn’t want to speak to anyone, but he rose and lifted the receiver.

“You have a call from Havana, Cuba,” the female operator said. “Please hold the line.”

“De Cuba, abuela!”

“Ay, Dios Santo,” Tíndara said. A call from Cuba was so rare, so complicated, and so expensive, it could only be bad news.

There was an interval of static, as if the call were from a distant planet.

“Please keep holding,” the operator said.

Through the static Thomas heard innumerable clicks, then the voice of a Cuban operator struggling to speak English with the American operator; the American operator not comprehending, asking the Cuban to repeat; then a long stretch of murky silence.

The oven reached its target temperature and buzzed. Tíndara opened the oven door and slid in the two aluminum trays.

“Oigo?” he heard at last. “Quien habla?”

It was his aunt Gloria, whom he had never met. Her voice was barely audible through the static. She and her husband, his grandmother’s son, had chosen to remain in Cuba. Tíndara often spoke of her son as a hero who had fought fearlessly against Batista. “Even when they beat him,” she’d say proudly, “he would not betray his compañeros but curse las madres of his jailers, so they would hit harder, knock him out, and have no choice but to let him rest.”

“Thomas…To-to-más,” the boy stuttered. His grandmother had warned him that the government listened in on calls and to be sure never to ask the wrong question, which could get the family arrested. Now he seemed to have forgotten all his Spanish words. His aunt sensed his paralysis through the static.

“Niño,” she said impatiently. Never having seen even a photograph of him, she thought he was still a small child.

“Put your abuela on,” she said in Spanish, as loudly as she could through the static. “Put Tíndara on.”

He handed the phone over to Tíndara, who grasped it anxiously.

“Oigo?” his grandmother said. “Gloria? Qué pasa?”

The TV dinners had started to cook, the turkey slabs awakening from their cryogenic sleep. Fumes of corn syrup, yeast, monosodium glutamate, rendered chicken fat, onions, and giblet gravy filled the kitchen with a sad, brown smell.

Thomas watched his grandmother’s lips start to quiver and her head tremble.

“No…it cannot be…cómo…?”

Tindara lowered the receiver and pressed it against her heart. She bit her lip, closed her eyes, and began to sob. Thomas wrestled the phone from her and put it to his ear. Only murky silence… He hung up and turned to his grandmother, helping her sit down, slowly, at the table.

“What happened, abuela?”

His grandmother’s face was disfigured, the right side of her mouth pulling spasmodically.

“My son…” Tíndara began, her voice thin and high.

“Abuela! Que pasó? Tell me!”

“My son…fusilado…”

And then it came: an animal-like wail, her face falling into her cupped hands like a stone, her back hunched over, her whole body shaking. Thomas ran out of the kitchen into the living room. A firing squad. He had only seen that in old war movies. But it had happened now, to his uncle. He wanted to call for help, but there was no one. He tried to open the window—it was stuck tight. He must call his mother. But she hated to be phoned at the House of Kleen and had scolded Tindara once for bothering her there. Tomás did not even know the number. He ran back into the kitchen as the cries became louder. The neighbors would complain. They were unforgiving, mean; the husband wore a stupid plaid golf cap and railed against foreigners. Thomas could think of nothing other than to drape himself over his grandmother’s bent, convulsing shoulders and absorb her pain, like the soldier in Vietnam that Mr. McNair had told him about, the one who’d thrown himself on a grenade and taken the blast to save his comrades. He held fast to her agitated body.

Then through his own tears he saw the white stove. It occurred to him that his very first memory of life was of seeing his grandmother standing in front of a white stove, in the house in Virginia, heating up a sterilizer—a round aluminum pot, scorched underside, black rubber knob and steam whistle protruding from the lid. Inside the pot there were round berths, like the chambers in a revolver, to hold his baby bottles in the boiling mix of water and Milton sterilizing fluid. He remembered bright orange flames lashing the pot, the whistle blowing shrilly, like a terrible plea for help, the plume of steam shooting heavenward…

Tíndara’s sobbing gradually became softer, her body calmer.

“You must eat, abuela.”

Thomas stood up straight and wiped his eyes on the sleeve of his sweater. His arms hurt from holding Tíndara. He took out forks and knives from a drawer and laid them on the table. He put on an oven mitt, then bent over and opened the oven door, ignoring the smell. He pulled out one of the aluminum trays, setting it down in front of his grandmother, who stared blankly at the myriad shining holes of the pegboard. Outside, a group of children chanted, “Ring around the rosy…” Tomás unfastened the foil cover from the four corners of the tray and lifted it. A hot fetid fog billowed up from the processed turkey, consuming their faces.

About the Author

Recent Comments