Photo by nImAdestiny

***

“Architecture from a Psychotic Viewpoint”:

A True Story of Psychedelic Serendipity and Hospital Design

by Kristen Hallows

This essay contains historically accurate words and phrases that may be considered insensitive or offensive today.

Like a swift descent into cold water, Kyoshi Izumi’s first sensation was that of muscle tightness. Despite an acute astigmatism, titles of books 15 feet away were legible without glasses. A partial deafness in his left ear, a closed door, and a distance of 30 feet did nothing to diminish the sound of his Chihuahuas’ toenails clicking against the floor.

Izumi heard and smelled colors; he saw sound. When he walked forward, time moved forward; when he stopped, time stopped; when he walked backward, time receded, but all of this happened while he was aware of the actual passage of time.

He was the Offenbach selection to which he was listening: “I was one note and all the notes, floating in a sea of sound.”

A friend appeared to eat a piece of chicken instantly yet endlessly. A stranger walking toward him on the sidewalk seemed to take forever to pass, his footsteps like a broken record. Contemplating the moonless prairie sky full of stars, Izumi felt that he was inside Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night.

This was Izumi’s first encounter with LSD in 1957.

His next would occur within the confines of mental hospitals, though he was not a patient. He was an architect invited by the Saskatchewan government in 1954 to assist in the modernization of its existing institutions and also to design a new facility as part of the Saskatchewan Plan, an initiative calling for the construction of smaller regional psychiatric centers.

The Provincial Mental Hospital at Weyburn, built in 1921, was cited as one of the worst mental hospitals in Canada in 1945. Izumi’s first visit took place in 1948 when his interest in designing facilities for the developmentally disabled led him to Weyburn:

A room full of mentally defective children, about 60 of them, in cribs butted together with narrow aisles between, who had all kinds of physical deformities, thin heads, large heads, short legs, long bodies, each in a crib, appeared as a visual embodiment of how different people can be. And yet it was apparent that their helplessness had certain similarities.

I suddenly realized that if they could be so different physically, how different mentally they must be—how they perceive things differently. I had a physical reaction to this experience—the food didn’t taste as good afterwards. The really bad ones were in the hospital basement, mixed up with the mentally ill. The physical aspects of the hospital wards were really depressing. Frankly I couldn’t understand how it could have been left like that even with the war. It was one hell of a mess.

Because of this experience my whole attitude toward the art of architecture changed. I no longer designed for architects. I am now trying to design for human beings.

Izumi returned to Weyburn to study the needs of schizophrenics, in particular, who were found to be cut off from the world thanks to their dramatically different perception of it. He was introduced to Dr. Humphry Osmond, Weyburn superintendent and champion of LSD’s potential to open a window of understanding between medical professionals and the mentally ill.

“One of the most encouraging things which has happened to me in recent years was the discovery that I could talk to normal people who had had the experience of taking mescaline or lysergic acid [LSD], and they would accept the things I told them about my adventures in mind without asking stupid questions or withdrawing into a safe, smug world of disbelief,” a patient shared.

LSD, mescaline, and others were called psychotomimetics for their psychosis-mimicking abilities. Osmond was a productive neologist, and he is credited with coining the term psychedelic (mind manifesting) to replace psychotomimetic and other ungainly terms, such as hallucinogenic and fantastica.

Others competed for the chance to enter our lexicon: psychephoric (mind moving); psychehormic (mind rousing); psycheplastic (mind molding); psychelytic (mind releasing); psychezymic (mind fermenting); and psychehexic (mind bursting forth). Psychedelic rose to the top because it was “clear, euphonious and uncontaminated by other associations.”

It also rhymed fortuitously.

Writing to Osmond in 1956, author Aldous Huxley attempted to flesh out a suitable term:

About a name for these drugs—what a problem! … Could you call [them] psychophans? Or phaneropsychic drugs? Or what about phanerothymes?

Phanerothyme—substantive. Phanerothymic—adjective.

To make this trivial world sublime,

Take half a gramme of phanerothyme.

Osmond’s reply?

To fathom Hell or soar angelic,

Just take a pinch of psychedelic.

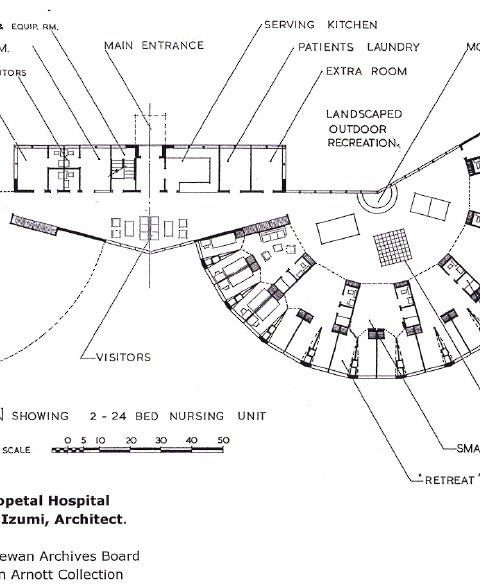

Osmond believed that buildings could either support human relationships (sociopetality) or discourage them (sociofugality). Drawing significantly from Osmond’s philosophies, the product of Izumi’s pre-LSD investigation was the sociopetal concept. Arthur Allen, employed by Izumi as a junior architect, recalled that the semicircular design, nicknamed the “Osumi” or “Izmond” plan, was intended to allow patients “the opportunity to make social decisions and move as they choose between private spaces, small parlours, and larger open spaces, selecting various levels of companionship in the process.

The sociopetal plan was dismissed as “too far out” by the administration, and neither the building code nor the hospital construction standards of the day would allow it.

“The circle is the most rigid of all geometric forms; as a shape, it forces itself upon us and tends to force the eye to one central point, eliminating the element of choice which Dr. Osmond so strongly advocates,” wrote architect Moreland Griffith Smith in response. A circle implies motion, Smith continued. It is endless.

Meanwhile, Dr. Alfred Paul Bay, superintendent of the Topeka State Hospital, stated, “I think there is room for an awful lot of imagination in the special area of mental hospital architecture.”

Izumi surveyed the literature and spoke with nurses and maintenance staff. He toured the wards, dined with patients, and even stayed overnight. Unfathomable today, he “sat in on interviews with patients and frequently participated.” Still, the mindscape of a mentally ill person remained elusive, so an LSD experience was arranged.

While we don’t know in extensive detail exactly what Izumi perceived as he walked the hallways and interacted with patients while under the influence of LSD, we can peek into the world of staff psychologist E. Robert Sinnett, who sat in the Topeka VA Hospital’s Hawley Auditorium in the fall of 1956 after taking 200 mg of mescaline as part of a doctoral student’s experiment. Thirty minutes in, he felt no effects. Then his left hand began to tingle.

Next came an almost uncontrollable urge to laugh at nothing in particular. Grimaces and stares indicated that his cachinnation was odd; when the need surfaced again, he ducked into a room in which a group was assembled.

“Quick, someone hand me a New Yorker—I feel a laugh coming on!”

A patient’s crude paint-by-number, previously unremarkable, now possessed more allure than an internationally acclaimed painting, the mesmerizing colors offering an Alice in Wonderland-style gateway to another world.

Sinnett glanced at his watch only to find that time held no meaning.

“The big hand is on 9, the little hand is on 4,” he said to himself several times before giving up.

While observing other test subjects taking a psychomotor performance test, he entertained a series of reveries. He imagined himself knocking the test off the table and watching with delight as the pages fluttered to the floor.

“Go fuck yourself!” he yelled at the experimenter in another daydream, laughing hysterically at the creativity of the epithet.

As he walked down the hallway, the wooden floor felt like canvas: elastic; yielding; bouncy. With each step, another portion seemed to rise. A cot was available in the room he entered, but he chose to lie down on the floor instead, his head against the baseboard at nearly a 90 degree angle; he wasn’t uncomfortable, and the cot wasn’t worth the effort. During a later attempt to rest, a hallucination—an oscilloscope-like grid atop a glowing yellow background—formed beneath his eyelids, ready to accept a mathematical function.

Upon walking outside, Sinnett knew the flagpole was about 50 yards away, but he felt that he could reach its top if he would just keep trying, and repeated unsuccessful attempts did nothing to dissuade him.

A 20 mph car ride down Huntoon Street was like a high speed trip through a tunnel.

Reports of tunnel vision weren’t uncommon, but actual measurements revealed no quantifiable change from the drug-free state, an experimenter shared.

Sinnett recalled dryly, “My illusion was not dispelled by this information.”

About four hours later, the session was terminated with Thorazine, an antipsychotic drug.

When you are thirsty, you have two traditionally-recognized options: one would be to relieve your thirst by obtaining a drink of water; the other would be to allow the condition to remain by doing nothing. While under the influence of mescaline during the experiment in which Sinnett participated, Dr. Philip Smith discovered a third possibility: not to decide at all.

“Nondecision” shouldn’t be confused with indecision; rather, it was the rejection of decision making, and it was quite satisfying.

The act of deciding drained Smith’s energy in his intoxicated state, and anything that removed the requirement was most appreciated. On a restroom trip, the door bearing the word MEN was a welcome guidepost, as was the sign imploring its readers to PLEASE FLUSH.

Returning to the testing room, Smith nondecided once again. He lay down in a patch of sunlight on the restroom floor.

“Bless your little heart,” he said.

He felt an exuberance of compassion and gratitude toward that area of sunlit floor, and he loved it for existing. Smith knew this was a silly thing to do, but it was massively fulfilling. He also knew he couldn’t explain it, but he didn’t—he couldn’t—care.

“Write drunk, edit sober,” is a piece of advice commonly attributed (perhaps mistakenly so) to Ernest Hemingway. “Write a bit tipsy, edit with coffee,” is the refined aphorism offered by The Expert Editor.

Different craft, different intoxicant—but writers, like architects, design something for others to inhabit, albeit metaphorically.

That charming merger of liquor, muddled foliage, and simple syrup isn’t just delicious. Writing sober, editing tipsy; writing tipsy, editing sober: this is my process for nonfiction writing in no particular order. Researching tipsy could be disastrous if it spills over into drunken territory, but once a solid grasp of a topic has been achieved, this classic psychelytic (to borrow one of Osmond’s coinages) doesn’t just boost the likelihood that words and concepts will appear, converge, diverge, and reappear in ways they otherwise wouldn’t.

This is also the closest I can get to the viewpoint of a reader.

I could put the draft away for a few days; I could take a walk; I could even take a vacation to gain a new perspective. Likewise, Izumi’s research could have continued, but, as he described, LSD unquestionably provided the quickest route to comprehension.

The bourbon clings to the side of the glass with uncharacteristic viscosity; its color and scent resemble a fine piece of oak furniture imbued with history. The initial sip, reminiscent of pure vanilla extract, is immediately followed by a demanding heat that saturates my very being by way of my throat and sinuses, like an imposing guest with no immediate plans to depart.

After a few more of these infiltrations, my first sensation is one of overall warmth and relaxation; then I pick up my latest draft.

Words are absorbed with the same intellectual voracity as those found in the newest issue of a favorite publication. I read not like someone who cares about the outcome, but like one who truly reads for pleasure. My mind is a clean, if palimpsestic, slate.

Liberation born of inebriation seems to be the origin of my new perspective; or, is it a new perspective that creates the feeling of freedom? I can’t be sure, but I make note of new ideas before they retreat to the unknowable place from which they emerged.

Izumi’s LSD experiences allowed him to understand how a patient could see himself flow or ooze out of a “leaky” room; how he could be “immobilized” by the omnipresent color beige; and how other features contributing to the building’s uniformity, such as terrazzo floors and suspended ceilings, could compound an already distorted concept of space and time.

“One of the phenomena that became clear to me after LSD was that I could see people walking, and could almost see their environment walking with them.”

Journalist Fannie Kahan wrote, “The average architect thinks in terms of space and volume, outside of oneself. Mr. Izumi was thinking of people, and oneself, in space and volume.”

It was important to be able to enter a space unobtrusively and easily, to be able to do this without the feeling of being on stage or of being observed, and to feel that you were not intruding on somebody else’s psychic space. This latter feeling was particularly acute when passing another person or groups of people in a “hard” corridor. I felt that the corridor should be “soft,” “absorbent,” and even “resilient,” so it could bulge out where necessary to allow another person to pass.

Under LSD, I experienced complete interdependence between mind and matter in terms of the perceived environment. Apparently, this projection and injection of your “psyche” into the elements around you is also typical of many of the mentally ill.

Opened in October 1963, the Yorkton Psychiatric Centre was the first regional facility constructed under the Saskatchewan Plan. The five rectangular cottages were named Prairie, Park, Pine, West, and York.

Most walls were a soft gray or green, and noise was noticeably absent throughout the cottages and in the underground passages connecting them to the administration building.

Bedroom ceilings were clearly defined to avoid the appearance of indefinite extension into the next room; beds touched the wall to provide a sense of security, and they were lower than the standard hospital bed to allow patients to place their feet solidly on the floor.

Hair stylists came to Yorkton once a week and charged their normal rates to ensure that patients felt like “members of the community in hospital for a time.”

Dr. G. A. Ives, Yorkton superintendent in 1964, said, “We lock doors here to keep people out, not to keep people in.”

Armrests were extended so that hands could be seen when placed on them; chairs had higher backs for increased support and a sense of enclosure; and the color and feel of upholstery was selected for comfort. The nurses’ station was designed and placed to avoid the look and feel of a police station or a control center. Overcrowding and overconcentration were avoided through attention to psychic boundaries instead of the number of square feet per person.

“It was much easier to be kinder in the Yorkton Center,” a staff member remarked.

If timing is indeed everything, Izumi’s story is an outstanding example.

In the same decade in which Yorkton opened, Saskatchewan became the first Canadian province to implement deinstitutionalization, a sweeping movement that eventually emptied mental hospitals in favor of treatment in the community. Yorkton provided mostly outpatient care, so few patients called it home.

There would be no follow-up study of Yorkton, and Izumi had no subsequent LSD sessions in the environments he designed.

The 1960s also saw the criminalization of LSD in various countries including Canada.

You may have heard that LSD was discovered by accident, but the substance itself was created quite intentionally.

Dr. Albert Hofmann, the Swiss research chemist who created the compound, explained that in 1938, the 25th in a series of lysergic acid derivatives, lysergic acid diethylamide (abbreviated LSD-25), was synthesized (artificially produced). An analeptic—a circulatory and respiratory stimulant—was the goal. When LSD-25 failed to wow the pharmacologists and physicians due to its being less effective than the leading analeptic at the time, testing was discontinued.

Five years later, Hofmann felt that LSD-25 may have more potential than previously understood, so he synthesized just a few centigrams for further testing in the spring of 1943.

Near the end of the process, he became extremely restless and slightly dizzy. At home, the daylight was unbearably bright, so he spent considerable time with his eyes closed “in a dreamlike state” during which kaleidoscopic colors, pictures, and shapes paraded continuously. Apparently, a trace amount had been absorbed through his skin.

Hofmann proceeded to use himself as a test subject. Higher doses produced more intense effects: the room spun, furniture was in continuous motion, and his neighbor had been replaced by an “insidious witch with a colored mask.”

I was taken to another world, another place, another time. My body seemed to be without sensation, lifeless, strange. Was I dying? Was this the transition?

Another reflection took shape, an idea full of bitter irony: if I was now forced to leave this world prematurely, it was because of this lysergic acid diethylamide that I myself had brought forth into the world.

There is a pilcrow-shaped road in the exurban Midwest that I call the “time capsule.” No bucolic title is displayed at the entrance to proclaim its official status as a housing development, but the homes share a uniting feature: none outwardly reflect the fact that we are currently living in the 21st century. As if to support this ethos, one driveway serves as a resting place for a Volkswagen Beetle with an historic license plate.

I enjoy walking through this neighborhood because I feel as if I’ve been transported. As someone born after the declaration of President Nixon’s War on Drugs, Izumi’s story inspires the same sentiment; but time capsules, like many drugs, produce fleeting effects quickly tempered by reality.

A search for the phrase “drug abuse” in Newspapers.com doesn’t produce a considerable number of hits until 1966. “Illegal drug use” doesn’t begin to appear with regular frequency until 1968. The zeitgeist of the 1950s and early 1960s is irreproducible; accordingly, it’s an entertaining yet futile exercise to try to imagine a world in which altered mental states are kindled by professionals in clinical settings for the purpose of experiencing someone else’s otherwise incomprehensible worldview.

LSD and mescaline were once viewed as “psychiatric tools,” not drugs of abuse; it must have been the absence of renown that may have given Izumi pause, if he experienced any at all. Izumi’s history with and attitude toward drugs aren’t well understood, but he did specify that he took LSD “for research purposes and not to search [his] soul as so many others had done.” His was more of a mission than an experiment: Izumi relinquished control of his mind to a foreign substance in order to view his surroundings through the eyes of someone understood to be insane.

“A major problem confronting the architect and artist is to overcome the apparent conflict between the free expression of the artist and the consideration of the needs and preferences of others,” Izumi wrote.

Weyburn inspired Izumi to balance this tension, and he chose LSD as his facilitator.

Over half a century later, The Perfect Storm author Sebastian Junger illuminated a similar conflict: “I’m very aware that I’m writing for readers, and I do everything I can to engage them, to make my writing accessible and compelling. At the same time, I try to be completely disinterested in what I think people will like. I’m writing for myself.”

Good writing can happen sober, but I believe the advantages to imbibition extend beyond the unmooring of views from their protective wrapping or the intensification of emotion that propels a cornucopia of possibilities to the page: an altered mental state can be an expressway to another outlook on your own work or someone else’s.

For this reason, whether we selectively rendezvous with a potent hallucinogen or continue in a comfortable, habitual relationship with coffee or cocktails, we may have more in common with Izumi than first thought.

About the author:

Kristen M. Hallows is a law librarian whose work has appeared in Law Library Journal; AALL Spectrum; Reflections: Narratives of Professional Helping; The Serials Librarian; and elsewhere. A longstanding interest in psychiatry and times gone by led her to discover the following headline published in 1965: “LSD Aids Architect in Mental Hospital Design.” Naturally, she had to know more. The result of her investigation is attached; a footnoted version is available upon request.

Kristen M. Hallows is a law librarian whose work has appeared in Law Library Journal; AALL Spectrum; Reflections: Narratives of Professional Helping; The Serials Librarian; and elsewhere. A longstanding interest in psychiatry and times gone by led her to discover the following headline published in 1965: “LSD Aids Architect in Mental Hospital Design.” Naturally, she had to know more. The result of her investigation is attached; a footnoted version is available upon request.

Top Photo by nImAdestiny

Recent Comments