The Entropy Room

by Arthur Shattuck O’Keefe

It occurred to Yugo, as he sat in his kitchen drinking coffee, that it had been almost three years to the day since he’d been pushed off the train platform. With a skill born of habit and necessity, he banished the thought from his mind as if it had never existed. He focused instead on his plans for the day: he had to catch the train to Yokohama, but before that he had time to write. He glanced at the stereo in the living room and decided to put on a record.

From the hundreds of albums on the shelves he selected The Essential George Gershwin. He was then surprised when instead of Prelude No. 2 for Piano he heard his own voice from the speakers saying “Forget that. You need to write with no distractions.” This had only happened twice before, presumably because it was truly necessary. Annoyed, he turned off the stereo.

He needed paper, so he got up and went to the entropy room. It was his name for the place where he kept miscellanea. He was reluctant to enter, yet drawn to it, for within he had recently perceived something out of place which he could not quite pin down. It rattled him. Really, though, considering that the room and its contents were illusory (a fact he couldn’t afford to ponder too deeply), he was not so much frightened as puzzled.

It was the smallest room in the house, not counting the bathroom. A single window faced north. There was a large pack of yellow legal pads sitting on the floor; also a spare mattress, two large half-dead potted plants, boxes of books, and boxes randomly filled with travel memorabilia, pens that had run out of ink, receipts, ticket stubs, dead batteries, etcetera. Many items were not in boxes but rather piled haphazardly on the floor. An unreformed crypto-slob, Yugo kept a tidy home save for this one island of chaos.

He pulled a legal pad out of the pack and noticed that the room was neater and more organized than before, with less dust. It was still in disarray, but the boxes were neatly lined up against the wall, with contents separated by type. Fewer things were scattered on the floor. This was it: it had been too gradual to notice until now. Nothing had ever acted like this before. He decided to ignore it for the time being.

Reflexively he thought: Somehow, this means I’ll be seeing that bastard with the umbrella today. He immediately put the thought out of his head and went back to the kitchen. He needed to write things down so he could keep everything together and make it more real. It was just before 8:00 in the morning and he didn’t have to work till the afternoon. Just as he began to write, his phone buzzed with a text message.

It was Mika. His friend, sort of, who taught English part-time at several universities like he did. They occasionally drank together and once he had gone to bed with her. Neither of them had tried to follow up on it and somehow it didn’t seem to affect their quasi-friendship. They were drinking buddies and it was a one-off. She was smart and pretty and easygoing and he wondered why he didn’t try to be her boyfriend. Maybe because it might distract him from the writing, which was crucial if he wanted to stay where he was.

“Can you come out today?” she asked in the text.

He wrote a reply. “I can’t today, sorry. Work.”

“Late afternoon classes, right? I mean can you come out for lunch?”

“I also have to go to the ward office this morning for some tax paperwork,” he lied. “So I don’t have time, sorry.”

She didn’t reply.

“It doesn’t matter,” he said aloud, looking at the phone. “You’re not even real.”

What the hell are you saying? He immediately thought. Shut up. She’s real. It’s real.

He switched the phone to silent, then put it face-down on the table. He looked at the legal pad he’d been writing on. He had barely started when Mika had mailed him. It was –. He looked out the window, then back at the paper and finished his sentence. It was cool and cloudy. He kept at it for two hours, then got ready for work.

He showered, shaved, dressed, and walked to the train station. He waited on the platform for the next express train.

None of this, he understood, was real. His morning coffee, the train station, his rented row house, everything he experienced day to day, every person he encountered, was nonexistent. Yet he needed it all to be real. (And as long as he was experiencing it, was it not, for all practical purposes, real? But it was better, a deep instinct told him, not to dwell upon it. Just carry the conviction within you, as you have for the past three years: This is reality.)

From the beginning, Yugo had instinctively understood that staying in this world required accepting its reality unreservedly, to internalize the conviction that it simply was (even if it really wasn’t). It was both easy and hard. The easy part was his immediate perception. The limited express train, which didn’t stop at his station, sped by. It was as real to him as any train he had ever seen, dream state or not. He would have felt just as much hesitance to jump in front of it as in reality. Food tasted just as good. So did beer, and Dreamworld hangovers were as nasty as in the real world. Mika, the only woman he had ever been intimate with in his Dreamworld, was as soft, warm, and alive with passion as any woman with whom he had shared such pleasure in reality. Writing things down in a journal made it all stay together. That was it. He just needed to make time to write every day. And then there was the hard part: while this morning’s discovery in the entropy room had been unsettling, he considered his only real problem to be the man with the umbrella. Recently he had been appearing more often.

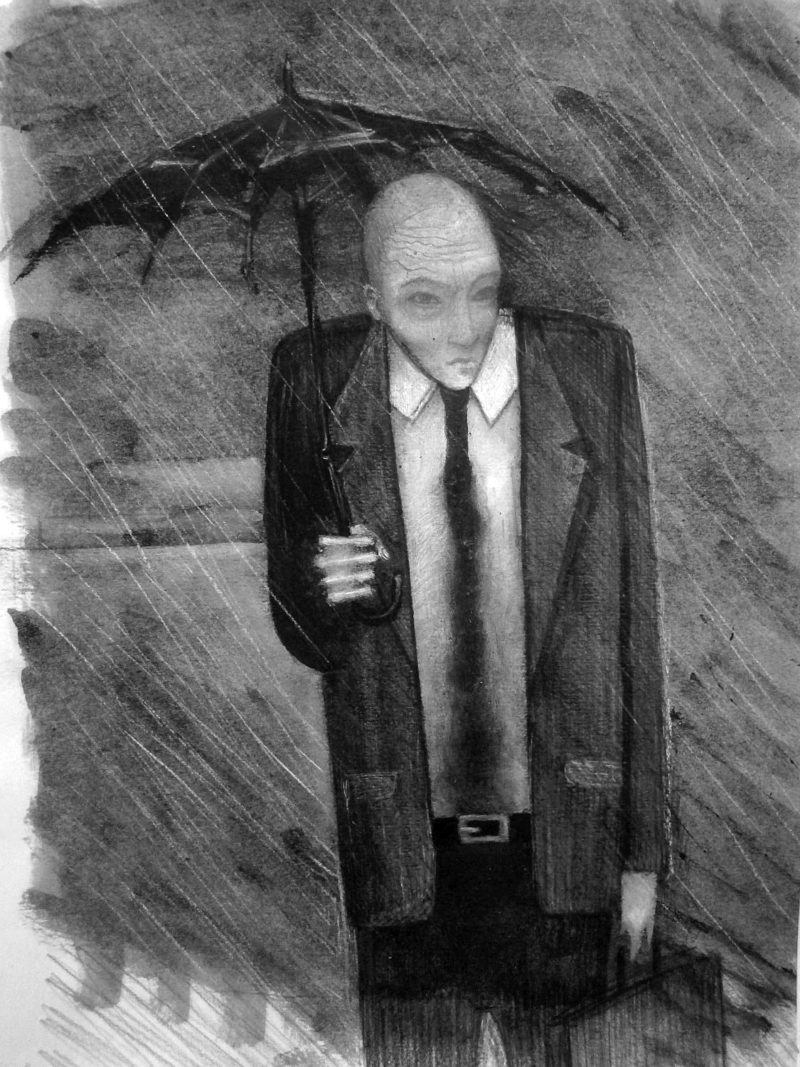

There he was again, standing near the platform escalator, his umbrella open. It was an outdoor platform and a cloudy but rainless day. His umbrella was large and black and each time Yugo saw it, it was slightly worse for wear. He could see a few small holes along the ribs this time. The man was slender and bald, wearing a dark suit and tie. He was pale-skinned, almost translucent; a white man? Sort of… and yet of no recognizable race. He stared at Yugo. No one seemed to pay him any mind.

Others were aware of his presence; that much was clear. People stepped around him. But somehow the open umbrella, with neither rain nor sun from which to protect its owner, got no stares nor even glances of curiosity. This did not exactly surprise Yugo; he was living in a world of his own construction, and “awareness” among its other occupants was a provisional term. He had always assumed that the man was an intruder from the real world, come to call him back. Beyond that, he didn’t want to speculate.

Come back, came the thought in his mind, which he felt impress him from without, from the umbrella man, who stared.

No, came the reply from within Yugo’s mind. The man continued to stare at him. Every time before this the umbrella man had stared for a moment longer, then turned around and walked away. This time he just stood there. And the station, the platform, the other commuters, everything began to fade out slightly just for a moment before returning to sharp, realistic relief. Except Umbrella Man. He didn’t fade. This was new.

A quiet sense of panic welled up within Yugo. Even as he stood locked in this silent and stationary combat, he considered (without wanting to) how all of this had begun.

***

While there is no Utopia, three years earlier Yugo had been more or less happy with his life. Single, childless, and happy to be so, he’d cobbled together three part-time teaching jobs which provided him with an ample income and plenty of free time. Then the accident happened.

It wasn’t exactly an accident – he was pushed. At least that’s what it felt like: something deliberate. But he couldn’t be sure, because he never saw who pushed him. He’d been standing on the platform at his connecting station, near the edge. The limited express train was coming through. He felt the sudden, strong impact in the small of his back. Then the fall from the platform. The oncoming train. The all-consuming terror. Then – blackness, and jumbled images, sensations. He could never remember actually hitting the ground, or being hit by the train. Which was good, he later thought.

Pain. Semi-consciousness. White uniforms. Bed. The daily pad calendar on the wall: Tuesday, May 6th. He couldn’t move. He could feel the parts of himself that were missing. With all his concentration, with every fiber of his being, he sent his thoughts to no one and nothing, to someone and something, to everyone and everything (to God…?): Don’t let it be real. Please. Or if this is truly real, let me live in a dream in which it isn’t so, where none of this has happened.

And so it came to pass. How, he didn’t know, and thought it best not to consider. But the man with the umbrella came soon after, always on the platform, always silently calling him back. And always Yugo had refused. The three university jobs, the daily commute, the people around him, his house and everything in it: they were all imaginary replicas of his real life, the one he had lived before the accident. Yugo could have had it all perfect, forgetting that it wasn’t real; it could have become the real world for him. Of that he was certain. But Umbrella Man, that son of a bitch, kept reminding him, just by his presence, that none of it was real. He made it harder to keep it all hanging together, and made the writing necessary.

***

The umbrella man continued to gaze at Yugo for a moment, then turned around and ascended the escalator. The express train to Yokohama arrived and Yugo got on.

It was well past the rush hour, and there were plenty of empty seats. He sat down and pulled the legal pad out of his bag to look at his latest entry. As always, he had written about the day before.

May 10 (Wed.) – Entry made on May 11. It was cool and cloudy, got quite chilly in the evening. Got up and wrote the entry for the previous day (May 9) as usual. Classes from 2nd period, so tail end of the rush hour. Classes went OK, but the social welfare majors in 3rd period still lack motivation. The French lit majors –

The train had stopped. The conductor’s voice came through the speaker system. “The train ahead of us has stopped due to a human accident. We apologize sincerely for the trouble caused.” Human accident. Jinshin jiko. The distinctively Japanese euphemism for “Somebody jumped in front of the train.” Or, less commonly, fell off the platform. Or possibly was pushed.

Yugo suddenly felt a vague, slight pain throughout his body. Things began to fade out again. He looked down at his journal.

The French lit majors are OK, though. They seem more interested and it wasn’t hard to get them talking.

Everything snapped back into sharp relief. The pain was gone.

The conductor spoke again. “So, feeling a bit of distress, are we? You don’t seriously think you can maintain this place forever, do you?” The other passengers all looked at each other and Yugo, nodding in agreement.

Nonplussed, Yugo stood up and shouted “Shut up! You’re supposed to do what I say!”

“And if we don’t? What can you do about it? ” asked an elderly woman sitting across from him.

He got up and went to the rear carriage, up to the window of the conductor’s compartment. He stared furiously at the diligent-looking young man who ignored him and spoke again into his microphone. “The train is about to move again. There was a human accident involving the train ahead of us. We deeply apologize for the trouble caused to our passengers at this busy time.”

It had never occurred to Yugo until that moment that he had never included the umbrella man in his journal entries.

***

That night he once again entered the entropy room. The boxes were now labeled: history books, fiction, travel items, tax documents, and so on. The inkless pens and dead batteries were gone. An empty bookcase lined the wall. The plants were lusher and greener. He stepped out and closed the door.

He lay on his bed, thinking. His hold on things was getting weaker: the entropy room less and less entropic, Dreamworld denizens implicitly declaring their non-existence. And the umbrella man was at the center of it, somehow.

He could not escape the conclusion: he was losing control. Yet it all felt so real. The bed he was lying on, the smell and softness of the sheets and the mattress, the texture of the wall as he ran his hand over it, the breeze wafting through the open window. So very real. How had he been able to do this? Don’t ask, he reflexively thought. But he couldn’t help it.

Sometimes he could forget, completely forget, that it was all an illusion. Most of the time he just kept the fact in a little compartment of his mind. Rarely it confronted him, unignorable, like a nasty migraine. Those rare moments were now becoming less rare.

Yugo realized that thinking about all this was a tacit acknowledgement that he was living inside a mental construct, which he knew he needed to avoid. Yet he couldn’t ignore the situation either. What to do?

He couldn’t go back. Not ever. Not to that. But if it became impossible to resist…

He looked at the journal on his nightstand. Inspiration struck. Why, he thought, didn’t I think of this before? But will it work? He confirmed today’s date on his phone. May 11. He grabbed the journal, went to the kitchen table, sat down, and began to write.

May 12 (Fri.) – Entry made on May 13. A shocking incident at the station.

I had afternoon classes, but had decided to get out early and stop by the bookstore. It all started out as an ordinary day, with mundane details. I found a pizza flyer in my mailbox; there were five macaws on the telephone line across the street; a delivery truck was parked in front of the Yamashita’s. A man outside the station was handing out some kind of political pamphlets (which I declined).

It was a few minutes before 9:00. Strangely for a weekday morning, there were only two other people on the platform, a high school boy and a middle-aged businessman.

Then another man walked over to where the other two were standing. He was thin and pale and bald-headed, dressed in a black suit. It was cloudy but not raining, yet he was holding an open umbrella which was rather worn out, with a few holes along the ribs. Anyway, the outbound limited express was approaching and – still holding the umbrella – he stepped off the platform right in front of the train.

The driver stopped, of course, but it was too late. It was awful beyond words. The train was obviously delayed, so I walked back home. I was later able to get to work on time because the station staff had…cleared the tracks.

He went to sleep, feeling hopeful.

At 8:50 the next morning, Yugo stood on the station platform. The pizza flyer, the macaws, the delivery truck, and the pamphleteer had all come to pass. The schoolboy and the businessman stood at the east end of the platform.

Elation and anxiety fought a relentless battle in his heart. At five minutes before nine, the man with the umbrella passed in front of him and walked, also, to the east end of the platform.

He stopped, turned, and looked at Yugo. For the first time ever, he smiled; the very faintest trace of a smile. But neither mocking nor malicious, no. Yugo felt a sudden sense of kinship and empathy in this smile which both attracted and repelled him, and he knew in that moment that the man with the umbrella would not die today.

The announcement came. “The Ebina-bound limited express will soon pass through. For your safety, please remain behind the yellow line.”

The tenuous pain then returned; everything began to fade out. Except the umbrella man. Yugo fought to keep everything in focus, but in vain. All became a silent white nothingness, except for himself and the man. They stood looking at each other.

Then it all came back, painless and clear. Yugo was once again on the platform, facing the pale man with the damaged and opened umbrella beneath a cloudy, rainless sky.

The businessman walked to the edge of the platform. He looked at Yugo and asked, “Seriously?” When the train had nearly reached it, he stepped off.

***

Yugo sat looking at the clock on the kitchen table. 9:05 AM. The newspaper lay in front of him. He looked down at the headline briefly, then gazed out the window. It was a sunny Sunday morning.

He had given up creating events for each following day and went back to writing about the day before, letting things take their course. For a month he had tried to use his journal to kill the umbrella man. Suicide by train, random stabbings, fatal heart attacks, any form of sudden death he could think of; the details of each day would be just as he wrote them, except the victim would be somebody else. And what he’d been doing seemed to have a ripple effect.

He looked back down at the newspaper headline.

Violent Crime, Suicide Surge Nationwide: Experts Weigh In. (Near the bottom: Related Story on Page 3: Yugo under Increasing Pressure to Maintain False Reality Framework; Man with Umbrella Unavailable for Comment.)

A former Ground Self-Defense Force member had somehow obtained a high-powered rifle with a telescopic sight and killed seventeen people from the roof of an office building before he was taken down by a special assault team. A nursing home caregiver had been arrested after poisoning forty-seven of her clients; forty-two had died and the other five were in critical condition. Random stabbings, bomb threats, and drunken street brawls had become common. Violent motorcycle gangs, after a decades-long decrease in numbers, had recently seen a surge in new membership correlating with an upward trend in school attrition. The nation’s commuter rail system had become dysfunctional due to dozens of daily suicide-by-train attempts (many successful), and the occasional commuter who was pushed. Nationwide gated platform walls had been proposed, but the cost was deemed prohibitive.

Yugo knew that he had caused all this. But none of the victims were actual people, just dream constructs, so he didn’t exactly feel guilty. Yet he also needed to consider all of this to be “reality” in order to make it stay, simultaneously trying to forget that he had made the self-prophetic journal entries. It was a strenuous kind of mental gymnastics, and the fadeouts had been increasing in both frequency and intensity. He occasionally began to wonder – but only briefly, because it risked another fadeout – whether suicide in the Dreamworld would cause his death in reality. He was tired.

His phone buzzed. It was a text from Mika.

There are no counterparts here of anyone you love. Except me.

He stared at the wall. A minute passed. The phone buzzed again.

You avoid me even as you keep me here. Why? Because I would distract you from writing?

He switched the phone off, pulled out its battery, and put it face-down on the far side of the table. Walking to the stereo, he pulled a forty-five from the shelf: “A Whiter Shade of Pale” by Procol Harum.

The amplified scratch of the needle gave way to the melody, haunting and deep, weaving its way into his consciousness, eliciting memories he needed to remember and wanted to forget. He had just turned 13. He’d heard the song, loved it, and translated the lyrics with a dictionary. It was then that he decided to major in English, his first step toward establishing a life he had truly enjoyed until –

The phone buzzed again. He turned it over.

Go look in the room.

He had not been inside since his first attempt at creating the future with journal entries. He had fought the urge daily. Needing to go in, he entered against his will.

The bookcase was filled with books, the boxes gone. The plants, luxuriously green, sat on an adjacent table. A small chest of drawers and a filing cabinet sat by the window.

Yugo picked up one of the plants and threw it on the floor with all his strength. The pot smashed into countless pieces, scattered and mingled with dark brown soil upon the floor. He did the same with the other plant. Soon the bookcase, the books, the contents of the cabinet and chest, everything was on the floor in disarray.

The song was over. Yugo shut down the stereo. He went to bed and dreamed.

***

He stood on a mountain road. It was a bright and snowless winter day, the surrounding peaks visible to the horizon. There were houses and cars, but no people. One house had a large sign that read Museum of Automata. Its front door opened.

Out walked an automaton. It was a humanoid patchwork of metal and wooden strips, bolted together. It walked toward Yugo in a slow, jerking gait. Reaching him, it stopped.

“Want to come inside?” The voice was tinny and grating. Yugo shook his head.

“Suit yourself. Would have been interesting for you, though.” Yugo said nothing.

“Have you noticed? You’ve never had a dream inside your dream. Until now. First and last time.” One of its bolts popped out and fell to the ground.

“Why is the room becoming organized?”

“Because everything else isn’t. The true entropy room has no boundaries.”

“What does that mean?”

“Has it ever occurred to you why you haven’t just moved somewhere far away from a train station? That’s where he always shows up.” Out popped two more bolts and a metal strip.

“Who is he?”

“You know who. That’s why moving away wouldn’t change anything. Just delay it.”

“Delay what?”

The automaton burst apart and fell to the ground in a heap of metal and wood.

Yugo woke up.

The blue light of his phone blinked in the darkness. It was a message from Mika.

Dreamworld equals entropy room. That small room in your house is just the last piece of everything you can impose order on. But it’s just about peaked, and you can’t sustain it. Sorry. xoxoxo♥

He went to the entropy room. Everything was restored. There was now a desk and a chair against the west wall, and an antique map of the world. The leaves of the plants had turned slightly brown along the edges, and a thin layer of dust coated everything. From outside he heard the faraway sound of angry voices, and then a gunshot.

***

A dark, cloudy Monday morning on the station platform. There is the pale, bald-headed man with his open umbrella, holding it up to the rainless sky. It consists only of its handle and ribs now, except for a few ragged strips of black cloth, like the skeleton of a beast consumed by scavengers. The outbound express approaches. Rain begins to fall.

Yugo runs toward the umbrella man. Reaching him just as the train comes alongside the platform, he pushes with all his might. For the second time, the man smiles his faint, gentle smile. Yugo’s wrist is grasped. It is not merely an iron grip: hand and wrist become one. They fall together in front of the train. There is no sense of impact as all fades to black.

***

Pain. Semi-consciousness. Bed. He couldn’t move. Dreading and needing to be awake, he struggled against his will to wakefulness. He could feel the parts of himself that were missing. He saw the daily pad calendar on the wall: Wednesday, May 7th. Two men were standing in the room, near the door. He knew them both.

Yugo stood in the hospital room. He saw the umbrella man, who stood facing him, and whose umbrella was gone. He saw himself in the bed, saw the parts of himself that were missing, even as he felt himself in the bed swimming in a sea of pain and drug-induced lethargy, looking at his whole standing self and the umbrella man.

The umbrella man looked at Yugo on the bed, looked at Yugo standing across from him, even as he perceived himself from both of them. “It’s time,” he said gently, “that we finished our conversation.”

“Who are you?” asked the standing Yugo.

“You know,” he answered. “You’ve always known.”

For a small eternity, Yugo stood and said nothing; then finally he released the last remaining vestige of the fruitless burden he could no longer carry. “Yes. But I need to hear you say it.”

“I am you. I mean –”, he paused, walked over to the bed, and spoke to Yugo lying there. “I am the part of you that is ready to die.” He glanced at Yugo standing by the door. “He is the part of you that isn’t. Wasn’t. It’s time.”

Yugo could not speak. In his mind he asked. And then? And then what happens?

The man with no umbrella placed his hand upon Yugo’s head and said, “I don’t know.”

Yugo closed his eyes. When he opened them again he was alone.

THE END

About the author:

Arthur O’Keefe was born in the Bronx, New York in 1966. Growing up in various locales on the Eastern Seaboard, he settled with his family  in the Adirondack Region of Upstate New York in 1977. Joining the US Navy in 1984, he was assigned the following year to serve aboard ships home-ported in Yokosuka, Japan. He has lived in Japan since then, returning to civilian life in 1989. After a brief stint as a liquor store warehouse worker, he taught English for the language school chain Nova from 1991 to 2012. Having earned a BA in East Asian and Japanese Area Studies from Regents College (now known as Excelsior College), he began teaching at universities in 2011 after earning his MA in Humanities from the Humanities External Degree program of California State University. He is currently a Lecturer of English with the Department of International Studies, Showa Women’s University, Tokyo. His writing has appeared in the Midwest Quarterly, the Japan Times and Tokyo’s Metropolis magazine. He lives in Yamato City, Kanagawa Prefecture.

in the Adirondack Region of Upstate New York in 1977. Joining the US Navy in 1984, he was assigned the following year to serve aboard ships home-ported in Yokosuka, Japan. He has lived in Japan since then, returning to civilian life in 1989. After a brief stint as a liquor store warehouse worker, he taught English for the language school chain Nova from 1991 to 2012. Having earned a BA in East Asian and Japanese Area Studies from Regents College (now known as Excelsior College), he began teaching at universities in 2011 after earning his MA in Humanities from the Humanities External Degree program of California State University. He is currently a Lecturer of English with the Department of International Studies, Showa Women’s University, Tokyo. His writing has appeared in the Midwest Quarterly, the Japan Times and Tokyo’s Metropolis magazine. He lives in Yamato City, Kanagawa Prefecture.

Recent Comments