Judith Skillman’s poetry has been nominated for the Pushcart, Best of the Web, the UK Kit Award, and is included in Best Indie Verse of New England to mention just a few honors of this prominent American poet and translator. Her work has appeared in many anthologies and journals and her work as an artist has attracted wide notice. The state of Washington poet has published sixteen poetry collections of acclaim; visit www.judithskillman.com

We are pleased to present this interview with Judith Skillman by Carol Smallwood.

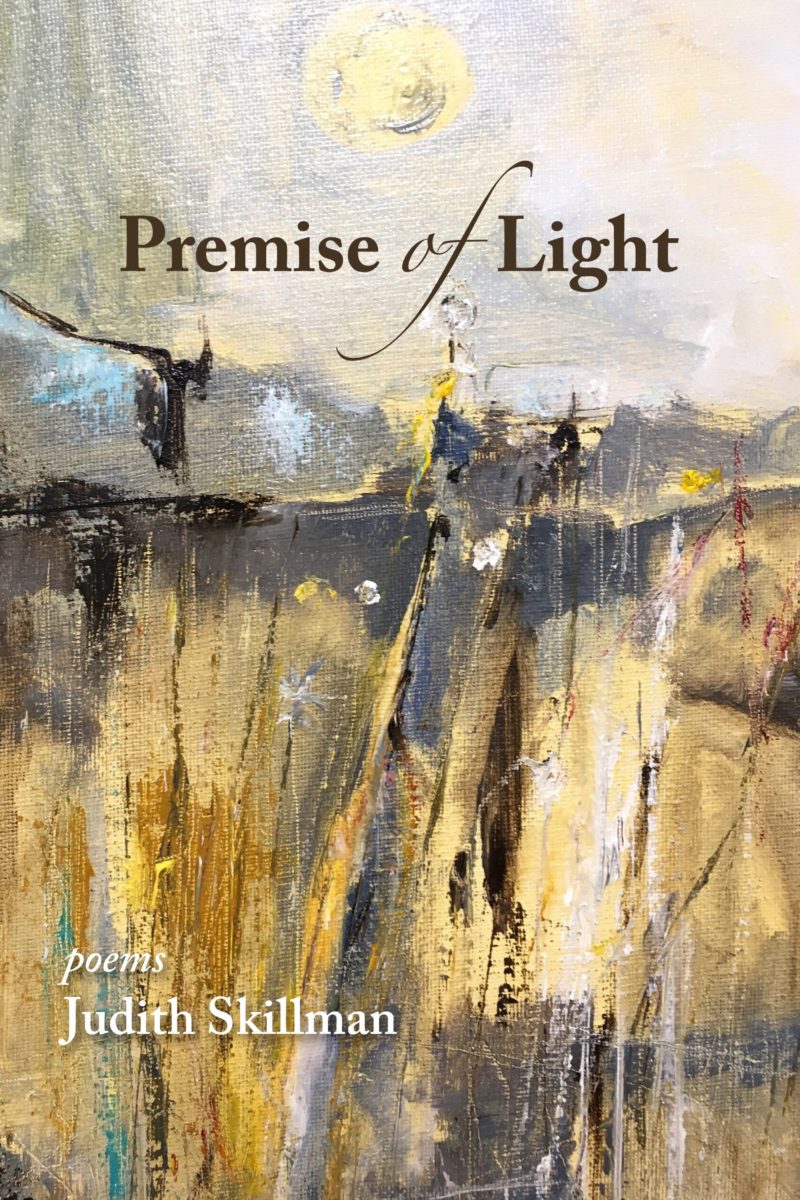

Smallwood: In Premise of Light you dedicate the collection to your mentor in art and your first poem mentions a famous artist. Please expand on your art study and the cover you did for this collection:

Skillman: I began taking art classes in fall 2014 at the Pratt in Seattle, and stumbled into Ruthie V., a wonderful teacher. Because my first major was visual art, the study of painting has been a gift. Ruthie V. is a talented painter and an excellent teacher. She is thoroughly versed in art history. I found I could employ Ekphrasis while learning about Lucien Freud, Édouard Vuillard, Emil Nolde and the myriad other artists who came alive through a mere skim of their lives, subject matters, and techniques.

The cover art comes from a small oil painting I did as an attempt emulate the work of an artist I love—Joan Eardley. This piece was a pass at her “Seeded Grasses and Daisies, September“. In visual art the student is encouraged to copy, unlike poetry, where both teachers and students consider it plagiarism to imitate another writer.

To me this disparity seems flawed, as the act of copying or modeling one’s work after an artist or a writer one admires may be one of the best ways to learn craft. That said, I did not in any way capture the essence of Eardley’s painting. What happened was more like translation, in which a different version appeared, barely recognizable as the original.

Wallace Stevens’ essay The Relations Between Poetry and Painting, printed in pamphlet form after his talk at Museum of Modern Art in 1951, reinforces the similarities between writing a poem and painting a picture. Both require composition and execution. Neither writing nor art ‘happens’ from inspiration alone. Both require forethought, planning, and then abandonment to the creative process—followed of course by revision.

Smallwood: I’ve read your previous collection, Kafka’s Shadow, and remember being truly amazed at your ability to portray a man in another age and language in your poetry. In your new collection you show your familiarity with other important historical figures. Where does this knowledge and ability to incorporate the past come from?

Skillman: Perhaps from my interest in these figures comes from a love of research, reinforced by the masters in English Literature from University of Maryland, and a stint at Catholic University School of Law. I’ve always loved the detective work of going deeper into a subject matter, whether biographical, artistic, or naturalistic, and seeing where that journey takes one. Of course things have changed in that regard. I can date myself as Pleistocene, having loved the card catalogue and the book-lined shelves of real libraries from childhood on.

The contemporary search via Google is different in methodology but yields similar fruit. You can veer off on a tangent, if you keep an open mind, and that seems important—to be willing to be led by strange details that narrow until they become obsessions. Writing is ultimately a form of learning. When we let our minds wander we’re able to find out the mysteries—hitherto unknown aspects of persons, places, and things. As for incorporation, the past carries its secrets in order to be mined.

Smallwood: in your poem “Maryland Tomato” you are very aware of the visual impact of the tomato on the table and take it outside into space with such ease. How long did it take you to write it?

Skillman: Thanks for this question! This piece took the form of a Ghazal, and that seemed to aid composition. The tomato was not actually from Maryland; rather, it was a Cle Elum (Eastern Washington) fruit. As soon as I saw it, memories of my mother’s garden in Maryland flooded back. My father had an observatory in the yard where my mother had her garden, and those two realities come together here, as I re-read the lines. That end word, “star,” can be used as a noun or a verb. The reference to “sun” and “red giant insides” brings in my father’s work—he was a solar physicist. As for the visual impact, the tomato seemed like a still life at the time, and that made me aware of the need for a multi-faceted background.

Smallwood: Hogweed, Cinnabar, and Eucalyptus as well as flowers are topics of your poems that reflect a knowledge of science and surveying of nature. Are you a gardener?

Skillman: What an interesting question. Unfortunately, the answer is no. I have a long-standing back injury and can’t garden. Even before, when I did some cursory work in the yards we’ve lived in, it made me feel frustrated and worn out, rather than pleased. I prefer walking and gardening on an instrument, such as the violin, though the latter has become more difficult to find time for.

But I love learning about the natural world—mountains, seas, plains, deserts. One of the greatest pleasures is looking with my myopic eyes at the details of flowers and plants. And there is always the sky—both day and night, in all seasons. The Northwest is home to a theater of clouds. Most likely this affinity for nature is something inherited. “Surveying” is a good word for taking stock of what is right in front of our own eyes, and seeing it as for the first time.

Smallwood: How did you become a poet? That is, did you write fiction, nonfiction before? What is your formal education background?

Skillman: Formal education includes a Masters in English Literature from the University of Maryland, and some courses in Comparative Literature and Translation from the University of Washington, as well as verse-writing from UW Extension. I have tried my hand at fiction and enjoyed it very much, but find now that applying the seat of my pants to the seat of the chair is difficult, partly due to the back injury. Re: non-fiction, I’ve written one ‘how to’: Broken Lines—The Art & Craft of Poetry (Lummox Press 2013).

Smallwood: Time is an important topic in your poetry. How do you handle this difficult concept to readers?

Skillman: Well, time seems to be the biggest circus of all. As humans I don’t think we can comprehend time, much less use language to discuss it. Physicists, especially quantum physicists—my sister, Dr. Ruth E. Kastner (transactionalinterpretation.org)—for one, have a better handle on the overall picture of space-time. Apparently what we ‘see’ is only the tip of the iceberg.

For the reader and writer of verse, memory is of paramount. We travel though life as through a landscape. What sticks around is important, and the poem demands that we pay attention to recurring memories and dreams. Quite often they are unpleasant, for poets at least. For me, trauma has been an unwanted theme, but one I try nonetheless to embrace. If one can access the context and the sensory details surrounding a moment, there’s a chance to move past it rather than remaining stuck, as it were, in time. The difficulty of conveying these ideas underscores their leading role.

Smallwood: Are you working on another poetry collection? What other activities such as workshops, teaching, do you do?

Skillman: I am planning to resume work on another collection when time allows. For the past decade or so I’ve run manuscript service where I assist in editing poetry collections, chapbook or book-length. See www.judithskillman.com At this point I am not teaching or doing workshops but that could change.

Smallwood: Light is mentioned in the collection as well as in the collection title. What does it mean to you?

Skillman: Light means everything! Perhaps not surprising given the physicists in the family. Those extend beyond my original family—my brother, Dr. Joel H Kastner is an astro-physicist and professor at Rochester University—to uncles, cousins and other relatives, and to my husband’s family as well.

One of my worst memories is from when as a young child in childcare or daycare in the home of someone whose blinds or curtains were drawn during the day. I recall I felt claustrophobic and depressed. I must have been under four years old and the profundity of the experience is/was undeniable.

Light is, of course, the opposite of darkness—that’s the cliché way to think about it. But more than that, the nuances of the natural world come alive through the unique lighting presented by each moment in its season, so to speak. All artists require light to create their work—dancers, cinematographers, visual artists, writers, architects—the list goes on. As I sit here watching Sequim Bay shade blurs to shadow, shadow blends from tans to blues and purples. Earlier, glittering suns shone on the water. Without invoking God, light is the gift we are offered every day.

Smallwood: As a reader the inclusion of the section at the end of your collections, “Notes” is much appreciated as they explain for example, who Bartholomeo Manfred is that appears in one poem. As a poet, I was amazed that none of your poems had appeared in previous collections, just in magazines. I became a reader of your collections with your 2014 collection, Angles of Separation. As one of your fans, I am looking forward to your next collection which never fails to astonish and delight.

Skillman: Yes, the “Notes” page can be overdone, but as I’ve said before, poetry is complicated. So whatever the writer can do to assist the reader is worthwhile. To accomplish that without intruding on a poem, the concept of a Notes page at the end a book works well. And just as we want each piece to function independently, I try to allow every collection to be uniquely its own; to stand apart from the others as much as possible.

Thank you, Carol!

About the interviewer:

Carol Smallwood is a multi-Pushcart nominee; she’s founded, supports humane societies, serves as judge and reader for magazines. One of her recent poetry collections is In the Measuring (Shanti Arts, 2018). She is an occasional contributor to Ragazine.cc.

Recent Comments