Intercourse in Absentia

By Cris Mazza

Contributing Writer

Apparently I have not lived the kind of life a writer needs. I have not, nor has anyone in my immediate family, recovered from an addiction, nor from a catastrophic injury or disease. I’ve never lost everything in a natural disaster, never been arrested. I was not abused (sexually or otherwise) by my parents, nor by any extended relative. The most lucid documentable unambiguous gender discrimination I’ve faced was when the local newspaper took away my paper route when they found out I was female. I have not come-out to and then been rejected by a hostile family. Sexual harassment … well, of course, but I wasn’t outright raped (notwithstanding grey-area incidents with complicated complicity). I have not had a special-needs child. I have not had any child at all. And yet, I wrote a memoir orbiting another thing that never happened to me. A book concerning the absence of it: orgasm.

Perhaps — although I didn’t realize it while writing — the absence of sexuality itself.

In Erica Jong’s sequel to Fear of Flying, sadly titled How to Save Your Own Life, the feisty and candidly sexual protagonist has her first “zipless fuck” with a woman. The oral sex seemingly goes on for hours, until the other woman barely, or maybe, has only a tiny orgasm. A groundbreaking lesbian sex scene in fiction … but: In this scene we are supposed to feel for and with the oral-sex giver for having to ‘endure’ doing it so long. She doesn’t like it, her “nose felt like it had spent its entire life in there.” Yet what of the woman who maybe had a small “shudder,” or else pretended to for the sake of her provider? She was the scene’s loser. She couldn’t even orgasm with oral sex, for Gad’s sake. She “made” Jong’s character do it “forever.” Not designed for compassion, she is only drawn with contempt, and on two fronts: her lack of sexual response, and that appalling putrid place where, regrettably it seems, the other’s attention must be focused.

I read that book at an unfortunate stage in both my sexual development and evolution as a writer. As a teen, Jong’s character longed for breasts and her first period, while I, in pre-adolescence, dreaded the onslaught of body changes. Somehow, though, I became a bold and audacious provocateur, “infamous for … explorations of gender politics and (sometimes deviant) sexuality.”[1] And in that identity, I hid my secret: I was living in the wrong time and belonged in the ’50s or ’60s with legions of women who had been branded frigid.

I’ve lived for decades with the identity of heterosexual female and a pronounced androgynous style. As early as memory goes back, I liked boys, hated my female body, frequently wanted to be a boy, didn’t want to touch a female body and never touched my own. I pretended to be a boy at girl scout camp and felt the power of primitive patriarchal animal attraction to a group of girls. I did not want to start my period or grow breasts. I still liked boys and wanted them to like me. I never used the word woman to describe myself. I liked being mistaken for a lesbian yet still did not want to touch another girl (or myself). I hated dresses and high heels and make-up (although I went through periods of trying). And I was terrified of sex.

I’ve tried two marriages. Sex was always painful in the first, frequently painful in the second, and never much more than friction in either case. Both marriages ended after years of celibacy. I’ve done couples sex-therapy and inter-vagina-electric-stimulation therapy for vaginismus. Basically I had a triad of sexual dysfunction, each maybe inflaming or reacting to the others. Sex was painful, nothing “called” me to need or desire it, and I’d never had an orgasm. I wrote about “a wall of thick clear glass between me and the sensual, lascivious world that is paraded, painted, filmed, flaunted, blared, boasted about, advertised, analyzed, danced to, dramatized, and even purred about softly in every subliminal white noise.” While the estimated percentage of women who has at least some form a sexual dysfunction hovers between 40 and 50%[2], percentages of women with anorgasmia — no orgasm at all, considering all forms of sexual stimulation — ranges, in sources, from 26%[3] to 10%[4] or as low as 5%[5].

If I were born blind or deaf, would I consider the lack of sight or sound as absence, something I lacked? Or do I only label it absence because of societal and cultural expectations? These sexual “norms” are present in almost every facet of daily life, not restricted to the media. The pejorative word frigid signals that culture deems this absence a damning personal flaw.

When Hugh Hefner died last year, the eulogies and obituaries gave him credit for starting the sexual revolution. Apparently the free and easy enjoyment of sex only needed someone (a man) to “start” it, and then it would happen. But what of those for whom it didn’t?

In my pre-sexual harassment-era college years, a mentor (yes, you read right) told me a story about a professor who “grabbed a girl after class and physically told her how he felt. He said he should have the right to follow honest impulses.”

“Wasn’t she scared?” I asked.

“Probably. But she liked it; she might have been hoping for it. If a girl hasn’t experienced those feelings by that age, there’s something wrong. They were married in three months.”

I was, at the time of this private conversation, still a virgin. And I was scared. And I didn’t want it. What was wrong? And where had the wrongness come from? At this time I’d already experienced those assertive hormonal boys, but hadn’t every girl?

It was in those years that I had my first pelvic exam. When the speculum was jammed in and cranked open, I wailed … then continued sobbing. The male doctor at student health services barked, “I’m not hurting you.” Not the first man to be putting something inside me and informing me that it didn’t hurt.

The media ratchet up expectations further, magazine cover blurbs that tell me what I’m supposed to want: Wild Summer Sex … Hot Late Night Sex … How to Get Exactly What You Want in Bed. And what the result of this desire should be: Sweet & Sexy Moves — Orgasm Guaranteed. If these examples are high on the crass, commercial, and sexist spectrum, how about a radio therapy host who tells her callers that orgasm is the best way to relax and de-stress. The examples of sexual expectations on social media are more numerous and the most effective at showing me my deficiency, because they can’t be dictated or influenced by corporate standards… can they? Besides the pouty pursed lips and pronounced-cleavage seductive selfies posted by serious authors, there are examples like a successful / intellectual woman’s update that she had worn out (yet another) vibrator, and photos from an all-woman literary event titled Sex and Power — to which this androgynous “explorer of gender politics” had not been invited — where some acknowledged the ‘power’ of alluring clothing. It’s difficult to deny, but also to articulate, the brand of power that comes from appearing, without apology, as your true sexualized self, if it is indeed true, and not created by a patriarchal culture that determines how one does and does not get attention / validation / voice. The sexualized universe of which I am increasingly not a member seems to be expanding.

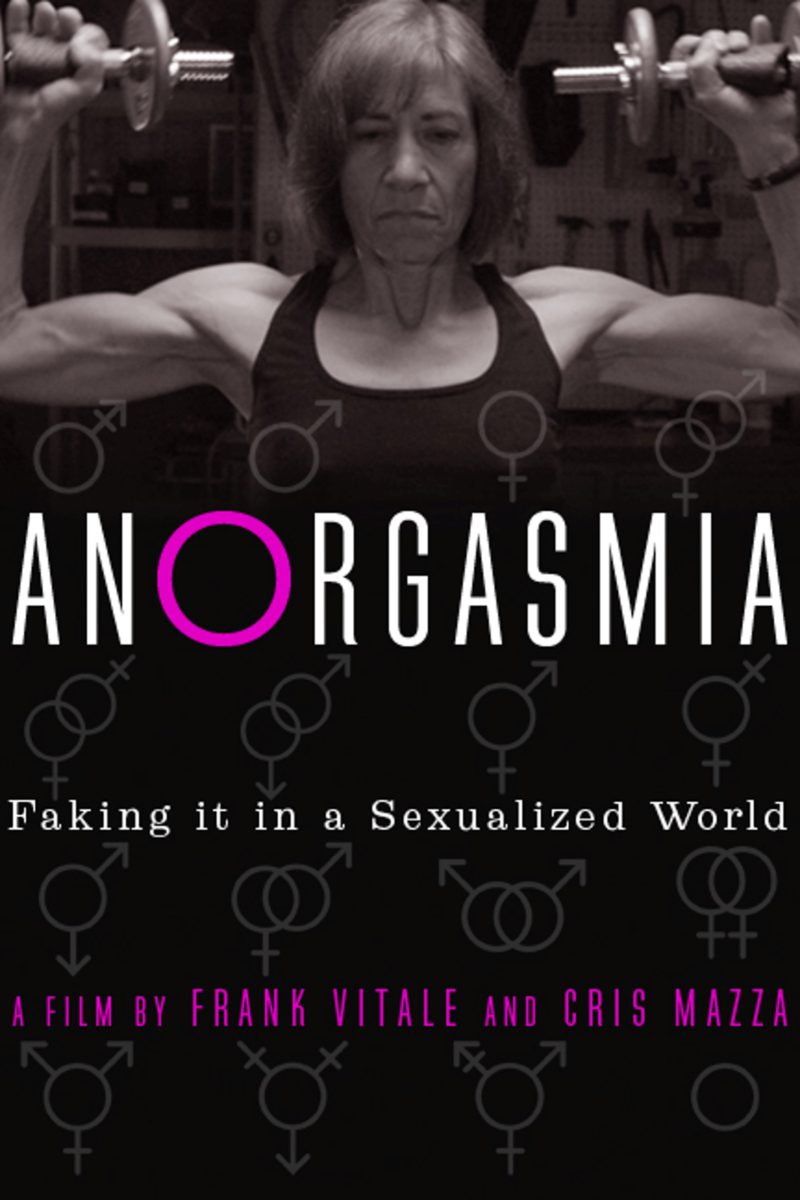

Anorgasmia … The Movie

The set called for silence. I slid in slippers toward a stool at the nucleus of screened lighting, ducked under the boom, and lifted my feet over the cables, careful not to jiggle any of the light or reflector tripods or jounce, even slightly, either of the cameras, which both had operators so close behind they were a fusion of human and instrument. From my place on the stool, the two cinematographers, sound engineer and director were fixed and silent silhouettes. Now I was in the center of the focused attention of lights, lenses, microphones, and four men, three who were decades younger than me, the fourth a decade older. I was dressed in a grey t-shirt and sweatpants. My hair was washed and brushed, thankfully covering the thin spot on my scalp. I wore not a particle of make-up. It wasn’t the independent low-budget project that eliminated costume design or make-up. Make-up was not part of my life, so I wouldn’t start here, on the set of a film I was co-producing, had written, and was starring in. A film that was the semi-fictional sequel to a memoir published the preceding a year. A film about my dysfunctional sex life and body loathing.

The director said Quiet. The head cinematographer said Speed. The director said Action.

I looked out the darkness, into none of their eyes, and said, “I’m a person who didn’t want to be sexualized, who didn’t want to have sex or any of the things that led up to it. … Wanting to be a boy was a way to avoid that … It felt like his penis was studded with razor blades …”

How and why would I write and star in a film about this? And let men have so much control of the medium? The latter issue is one I haven’t yet entirely unpacked. The former: it was a way to playact my way to some clarity about my sexual self, if I even had one.

Something Wrong With Her is the memoir that finally faced my sexual situation head-on. While writing it, I was also reuniting with a man I’d known from age 16 to 30. More disorienting, he’d been one of the determined boys breathlessly wanting something from my body. Now a man, he felt responsible for my life of sexual dysfunction; he wanted to be the solution. For a year of correspondence, before the reunion was complete, I believed he could be. But, despite receiving from him forms of physical enthusiasm I’d previously not experienced, I still felt no “call” of desire, and still no orgasm. Now as much of a life-partner as a man can be, a man for whom my androgyny is as much a part of what he loves as is how I laugh and crumple against him when he does a quip or impersonation, he made the film with me, beside me in scene and out, bearing my frustration and disillusionment … and his own bewilderment over what I was “saying.” This complication is not the same as the one involving the all-male film crew. He, or who he is to me, has to be part of any identity I profess.

Essentially, after I wrote a book that contained more than one story that developed as I wrote, I then helped create a film sequel where I learned what the real subject(s) might be while the cameras sped. Assisted by Google, plus a woman who agreed to appear in the film as an advocate from an asexuals group, I was basically making a film ass-backwards, researching while filming. Gender diaspora, asexuality, hetero-romantic, non-binary — identities that hadn’t been offered or available in my teens and 20s. But film technology was too fast, and I didn’t learn enough before we wrapped. Nor could I even stand to watch the various cuts I was sent during editing. Unable to go back and re-do certain scenes, to let my “character” explore the identity she couldn’t quite grasp, all of it desperately thwarted by her age and muddied by her devotion to a partner, I had to let filmmaking’s usual brand of teamwork help the final product, Anorgasmia, become somewhat less confused than I (still) was.

Four years out from the wrap of filming, a year out from the film’s release, no longer looking for “solutions,” I continue my private evolution. Androgyny is easy enough to claim, but I still can’t say any of those other labels or identities I absorbed during the filming process satisfy the questions society seems to demand I answer. Perhaps sexual dysfunction is expected to be a means to knowing who I’m supposed to be, but the reality is my uncertainty and confusion are more the collateral damage of being anorgasmic in a highly sexualized world.

About the author:

Cris Mazza’s next novel is forthcoming from BlazeVox Books. Her last book was Charlatan: New and Selected Stories chronicling twenty years of short-fiction publications. Mazza has seventeen other titles of fiction and literary nonfiction including her last book, Something Wrong With Her, a real-time memoir; her first novel How to Leave a Country, which won the PEN/Nelson Algren Award for book-length fiction; and the critically acclaimed Is It Sexual Harassment Yet? She is a native of Southern California and is a professor in, and director of, the Program for Writers at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

[1] Gina Frangello http://experimentalfictionpoetry.blogspot.com/2008/08/cris-mazza-interviewed-by-gina.html

[2] WebMD

[3] “Prevalence and related factors for anorgasmia among reproductive aged women in Hesarak, Iran” by

Mitra Tadayon Najafabady, Zahra Salmani, and Parvin Abedi

[4] Via The Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada in “What I Learned From No-Orgasm Sex” by Hayley MacMillen (Refinery 29)

[5] The Case of the Female Orgasm: Bias in the Science of Evolution by Elisabeth A Lloyd

Links in the text:

Cris Mazza (by-line) … http://cris-mazza.com/

vaginismus (p 2) …https://www.healthline.com/health/vaginismus#overview1

Anorgasmia (p 6)… http://anorgasmia-film.com/_1./Home.html

Something Wrong With Her (p 5) … http://jadedibispress.com/product/something-wrong-with-her/

Previous by Cris Mazza in Ragazine:

old.ragazine.cc › 2013/08 › cris-mazza

Interview with Cris Mazza in Ragazine:|

http://old.ragazine.cc/2011/06/chris-mazza-authorinterview/

Recent Comments