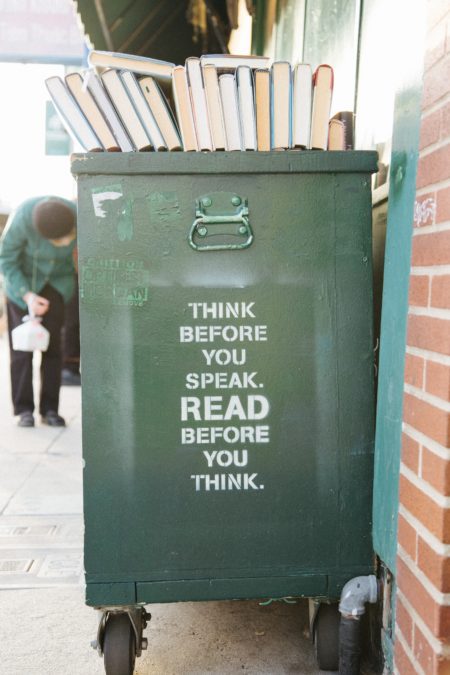

Photo by Element5 Digital on Unsplash

Critical Literacy, Economic Growth, and the Standards Movement:

Are We Speaking the Same Language?

by Nancy Barno Reynolds

Education Editor

The introduction of ESSA (2016) laws mandated by then-President of the United State, Barack Obama, required states and public school districts to create – and adhere to – a set of common understandings regarding goals and objectives of grade-level curriculum, p-12. Technically, these new standards allowed for the personalization and replacement of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS), a mandate introduced in 2010 which set the parameters of a literate individual in 45 states as “having mastery of English” (CCSS, 2010) – similar to the early literacy goal at the turn of the century. However, these goals also focused on an incremental understanding of subject areas deemed crucial to college and career readiness through mastery of procedure and concepts (CCSS, Introduction, 2010) – quite different from the basic literacy skill requirements of the early 1900s. The Common Core State Standards provided specific parameters for teaching and assessing literacy proficiency across content areas besides English Language Arts (ELA) and Social Studies. These parameters defined expectations for a new understanding of literacy: the critical use of literacy.

According to the CCSS, a critical use of literacy required the ability to interpret text using skills which promoted the logical untangling of facts, decoding of text, and dissection of plot based on knowledge of literary devices (CCSS ELA, 2010) — a mastery of language skills, in other words, without, necessarily, a global context for socio-political understanding or for the power of language use. Despite this, a variety of contemporary definitions of literacy still exist, some outside state parameters of literacy for the 21st century. Many – even from educational institutions and businesses – may tend toward a broader and more fluid understanding of literacy beyond the expectation of state standards, introducing a conceptualization of the term that is both discursive and situated (Davies & Harre, 1990). Consider this statement on literacy in the workplace from the president and vice president of research at Imperial Consulting Corporation, a company that “advises businesses and communities on skilled job and talent management,” including “consult(ing) on career-technical education, adult literacy, job preparation programs, and career academies”:

We define literacy as the degree of interaction with written text that enables a person to be a fluent, functioning, contributing member of the society in which that person lives and works. This definition assumes that no single fixed standard for literacy exists. We believe that literacy standards are constantly being shaped by the social, economic, and technical demands of a particular time and place. (Literacy in America, Gordon & Gordon, 2003)

In a recent conversation with one of the authors of this statement, Dr. Edward E. Gordon spoke about literacy and the workforce, including the role of industry in literacy training: “There needs to be regional efforts to rebuild the educational to employment path.” However, he was quick to point out that he is talking about the ability to develop high level reading and writing skills in students, k-12 – including cursive – for comprehension, fluency, the development of the brain, and for the expansion of creativity. “We’ve got to get more kids reading, instead of scanning social media.” He says that there seems to be a disconnect between intelligence and literacy that should not exist, according to NAEP scores that measure literacy across the country: 66% of children have average intelligence and 13% have above average to genius level intelligence, yet only “about a third” of students test successfully for reading at the 12th grade level upon graduation from High School. This is damaging to the workforce and to the functioning of a healthy society.

However, he says, that may be changing: “The new generation – generation x? – is reading more than millennials. Is that because of Harry Potter? If so, great!” Gordon’s goal is to teach all children to “learn how to learn”, citing the particular gaps in achievement and literacy for marginalized communities: “We’re just not enabling enough people (to become highly literate) – whether they’re Black, Hispanic, disabled, or immigrants — to make it in the job market.” He says that the low standards of 19th century basic literacy – literacy for transaction or for a minimally skilled work force – are not the goal. “The 19th Century was a time for job training – now called ‘boot camp’(!) – without literacy! We need to teach students to be good readers before teaching them how to code,” adding: “Do they have an attention span, imagination, vocabulary to read and understand a book? If companies aren’t training people in literacy, we can’t grow our economy. We need a higher level of literacy” in part, says Gordon, so students, workers, and voters can “separate propaganda from the truth” and think outside the box in the workforce. Gordon asserts that knowledge of history is also crucial to understanding: “That’s why all those crazy people voted for Trump. They never learned how to learn.” He is, in part, referring to critical literacy.

Critical literacy, for some, may be defined as an amalgam of literacy expectations which combine basic literacy skills with recognition of the power of language and of the individual (reader, writer, speaker, and listener). Ken Teitelbaum, in his essay “Critical Civic Literacy in Schools: Adolescents Seeking to Understand and Improve The(ir) World”, succinctly states a definition of critical literacy as “…having the ability to read, write, speak and listen in meaningful ways” (2010, p. 12); meaningful to the individual interfacing with myriad modalities of literacy. Michelle Knobel (2007, p. vii) describes critical literacy as “…concerned with critiquing relationships among language use, social practice and power.” Ira Shor, describing critical literacy through the work of Anderson & Irvine says “…critical literacy is understood as ‘learning how to read and write as part of the process of becoming conscious of one’s experience as historically constructed within specific power relations’” (1999, p. 82).

The common threads of a critical literacy understanding (which set it apart from basic literacy and content area literacy, for instance) include an understanding that language is situated in context, and therefore may have multiple interpretations, and that the individual is an important part of those interpretations. Louise Rosenblatt, the mother of “Transactional Reading Theory”, may explain the importance of this discursive relationship between a reader and text, this “transaction” between personal experience and written word, as being essential to meaning-making. Literacy, in other words, should be considered to be subjectively located within the individual (1986).

Though literacy has become the bedrock for understanding across curriculum, including in history/social studies, science, and “technical subjects” (CCSS0), its framework shares few characteristics with critical literacy, focusing instead on a critical use of literacy. A “critical use” of literacy, in CCSS terms, requires the use of reasoning, probability, and analysis to interpret texts, but no similar mandates reflect the power of language, the role of the individual and/or context of language use, nor an understanding that language may not be neutral. Conversely, critical literacy, formerly referred to as “translation literacy” (Meyers, 1996, pp. 134, 152), defines language use contextually, discursively, and as having the power to transform (Knobel, 2007; Lewson, Flint, & Van Sluys, 2002; Mulcahy, 2011;Basabe, 2008; Morrell, 2008; Shor, 1997; Lankshear & McLaren, 1993; Luke, 1995, and many others). This distinction between a critical use of literacy and critical literacy may create contention around issues of equity, access, and excellence, as well as for projections of success in the workforce. Though not mandated or tested by many ESSA standards for English Language Arts (ELA), critical literacy may be essential to growth, and ultimately, transformation — of individuals, businesses, and ultimately, communities.

*Parts of this essay may appear in previously published works by the author.

About the author:

Dr. Nancy Barno Reynolds is on the Graduate Literacy Education Faculty, SUNY Oneonta and former Director of Inclusive Adolescence Education at Cazenovia College in Central New York. Her work on the use of critical literacies for transformative and democratic teaching has been presented at both international and national conferences. You can read more about her in About Us.

Dr. Nancy Barno Reynolds is on the Graduate Literacy Education Faculty, SUNY Oneonta and former Director of Inclusive Adolescence Education at Cazenovia College in Central New York. Her work on the use of critical literacies for transformative and democratic teaching has been presented at both international and national conferences. You can read more about her in About Us.

Recent Comments