Internet Archive Book Images

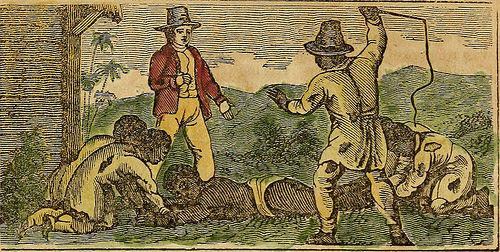

Image from “The American anti-slavery almanac, for … : calculated for Boston, New York, and Pittsburgh ..” (1836)

Before We Have an Honest Discussion About Race

We’re socialized — or perhaps it’s our inherent nature — to suppress the evil that surrounds us. This is why an individual can post “having a great day at the beach” on Facebook while, on the same day, Boko Haram in Nigeria is kidnapping hundreds of young girls from their school. To feel happy and emotionally fulfilled in a world where children suffer in poverty seems almost sociopathic… unless you block out the bad stuff from your mind. It’s a coping mechanism.

And it’s easy to expunge slavery from our collective memory. Because we feel no relation to its time and place, no emotional connection to its inhumanity. Surely, slavery must have been bad — but life was hard for everyone back then and, more importantly, we’re different now. We’ve changed.

That there are people alive today who survived the Holocaust is an obvious reminder of Nazi German atrocities. Even without those personal stories, however, the Holocaust still resonates through photographs and film. Images of American slavery, meanwhile, are limited to childlike etchings. Slave photography does indeed exist, but as portraits and posed shots. In contrast, 19th century scenes of forced labor and brutality in the Deep South are illustrated in a surreal way, visually more reminiscent of ancient cave drawings than of the graphic, familiar scenes of Nazi concentration camps.

Since most people today are familiar with the Holocaust through black-and-white imagery, it’s no surprise that modern media representations of the genocide are in black-and-white. In other words, Schindler’s List would have lost much of its emotional power had it been released in color. Society recognizes the Holocaust in black-and-white as a human evil to which they can relate.

American slavery, on the other hand, is unrecognizable in any modern context. Yes, films like 12 Years a Slave reveal harsh moments of violence and a lack of compassion. But those evils happened so long ago. The characters’ way of dress and their manner of speech is so very long ago. The movie looks different from the world we understand now. One tends to watch the scenes as “people doing bad things to each other,” rather than “This really happened.” In 2015, it’s easier to comprehend mass slaughter than a slave auction.

Hence, to have a serious conversation about slavery is to make it relatable — first, by reevaluating the timeline.

As a matter of fact, the institution of slavery did not exist so long ago. American slavery is not ancient Rome. In relative time, American slavery is closer to the rise of Netflix than it is to say, the time of Christopher Columbus.

The country’s current oldest living woman was alive at the same time as abolitionist Harriet Tubman.

Clint Eastwood was alive at the same time as Orville Wright, who was alive at the same time as Andrew Johnson, Abraham Lincoln’s Vice President who, once in office, immediately took executive measures to oppress black people.

Madonna was alive at the same time as Ernest Hemingway, who would’ve been alive at the same time as Lincoln, had Lincoln lived a full life.

George Washington died almost 70 years before slavery was abolished. Legendary comedian Groucho Marx was born only 25 years after the end of American slavery. Actress Gwyneth Paltrow was already 5-years-old when Groucho died.

There are Holocaust survivors alive today. And there are many people who were alive during the Holocaust who were alive during the time of slavery.

So what happened between the 13th Amendment, the 1865 Constitutional law abolishing slavery, and the 2015 politically conservative view that racism is no longer a legitimate factor? Did people change? Did society change? How? When did this happen? In 1866, right after slavery was banned? In the early 1900s, when President Woodrow Wilson, who resided in South Carolina during the Reconstruction period, reversed the previous administrations’ racial integration policies? When did people change? When did racist beliefs come to an end? During the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and the 1960s, when police departments and other government agencies led violent assaults on black protesters?

Slavery happened. Not long ago. Slavery didn’t end with united agreement. Rather, it ended through bloody battle, which is to say that many Americans still strongly believed in the right for a person of one race to hold ownership over a person of a lesser race. When did these people, who were willing to fight and die for the rights of white men to keep underage black girls as full-time, unpaid prostitutes caged in a nearby hut, change their belief system? Did these people teach their children racial tolerance? Did their children teach their children to love one another? When did the people of South Carolina see the error of their ways? 1970?

The same Americans today who don’t believe that human beings could have evolved over millions of years believe that human beings evolved over the past 50 years.

Racism cannot end until we have an honest discussion about slavery. Regardless of political opinion, all racial strife that exists today, all racial stratification, all racial social segregation is dependent on the slavery that came before it, that existed in America. Slavery happened. Not that long ago.

Human cognition has not changed over the past 150 years. Our biological ability to think, the way the brain works, is the same now as it was in 1865. The 150 years that separate legal slavery from a pathetic, angry loser murdering nine black people in a church barely register a blip on the human timeline.

White plantation owners hated their slaves. You don’t shackle those that you love. You don’t whip those that you like. To forcibly separate families is not a feeling of “indifference”; it’s hate. So what happened in society that the hate disappeared? Integration? Laws seeking to end discrimination? But the slave owners were opposed to integration. They supported discrimination. Slave owners’ children were taught to oppose integration, to support discrimination. So when did the human condition change? When did those who were once racist change their way of thinking? How did this happen? The racists all just died off? And are these questions not part of an honest discussion about slavery?

Long-time South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond, famous for conducting the longest solitary filibuster in Congressional history (over 24 hours!) in an effort to stop civil rights legislation in 1957, practically died in office in 2003, at the age of 100. A politician who wore racism on his sleeve, who dedicated his public service in pursuit of oppressing black citizens, Thurmond’s only hurdle to winning yet another term in the Senate was death… which is to say that in 2003, the majority of South Caroline voters still supported an outspoken racist. So when did the racist feelings stop? In 2005? In 2010? Why? What happened to finally free all these South Carolinians from the emotional handcuffs of hatred? Strom Thurmond was alive at the same time as Suri Cruise. Had Abraham Lincoln lived to the same age as Strom Thurmond, then Lincoln and Thurmond would’ve been alive at the same time.

Lincoln, of course, only lived to the age of 56, shot to death by a lone white supremacist and Confederate sympathizer, just as — in 2015 — nine innocent black people were shot to death by a lone white supremacist and Confederate sympathizer.

But people are different now than they were in 1865, we’re told. We used to have hate in our heart. But not anymore. Something changed. Racism ended. That’s the narrative.

One day slavery was legal in America. The next day, it wasn’t… well, sort of. Slavery went away. But the racist attitudes that allowed slavery to flourish for so long, that allowed segregation of schools and hotels and drinking fountains, that rationalize economic inequality and outrageously biased legislation and law enforcement… that didn’t just go away the next day. So when did it go away? Fifty years ago? Ten years ago? Yesterday? Or will it go away simply by removing a Confederate flag from public display?

We need to begin with an honest discussion about slavery. We need to talk about how human beings — biologically, emotionally, and intellectually no different than the human beings that we are today — allowed this ocean of horrors to happen. And we need to talk about how, in 2015, human beings have the same mental capability to hate and to enslave, and that national strides of equality never made it into the collective conscience. Rather, these gains were won through a continuous war between the tolerant versus those unwilling to relinquish their power.

But we haven’t begun this discussion. Instead, we rationalize the “long ago” institution of slavery as “complex,” and we replace the word slavery with terms likehistorical pride and states’ rights, and we bring up the “decent” slave owners who treated their property with kindness. Or we justify our history by arguing about Africa’s role in the slave trade. Or we don’t talk about it at all.

Slavery happened because of a burning racism whose flames extended well beyond even the Southern states. And then it ended. And nobody talked about it. Now it’s time.

Follow Galanty Miller on Twitter: www.twitter.com/galantymiller

Recent Comments