January Jazz: What’s Hot

When You’re Coming in From the Cold

by Greg Stewart

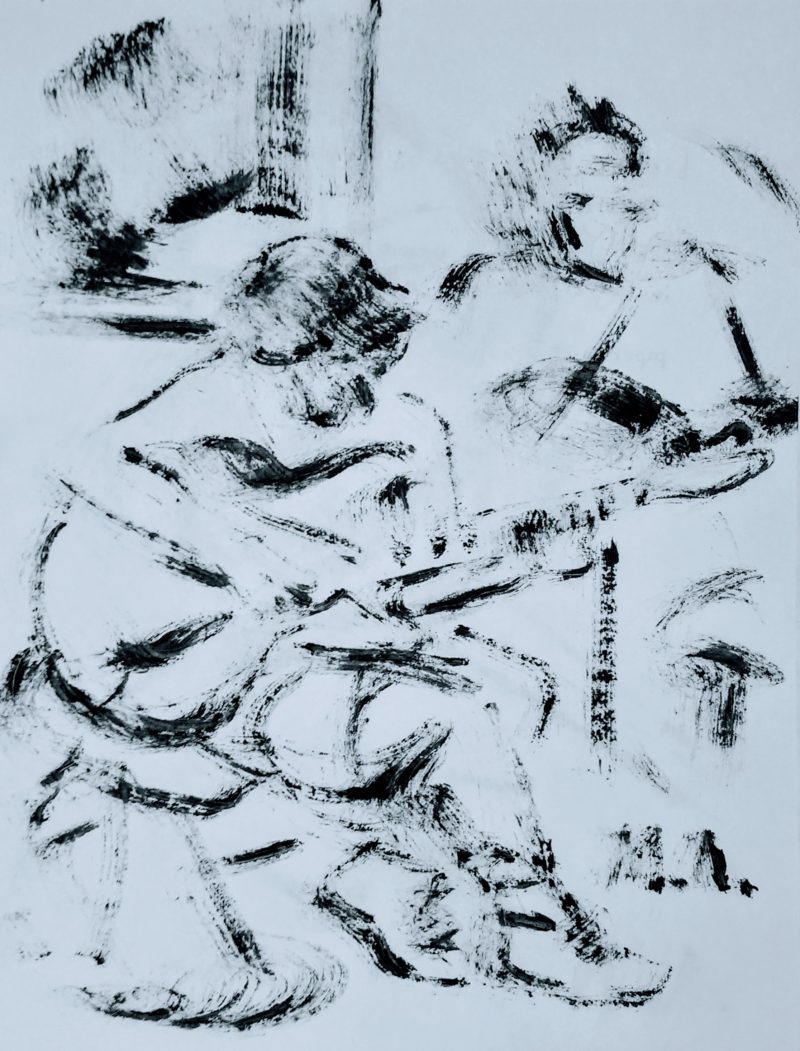

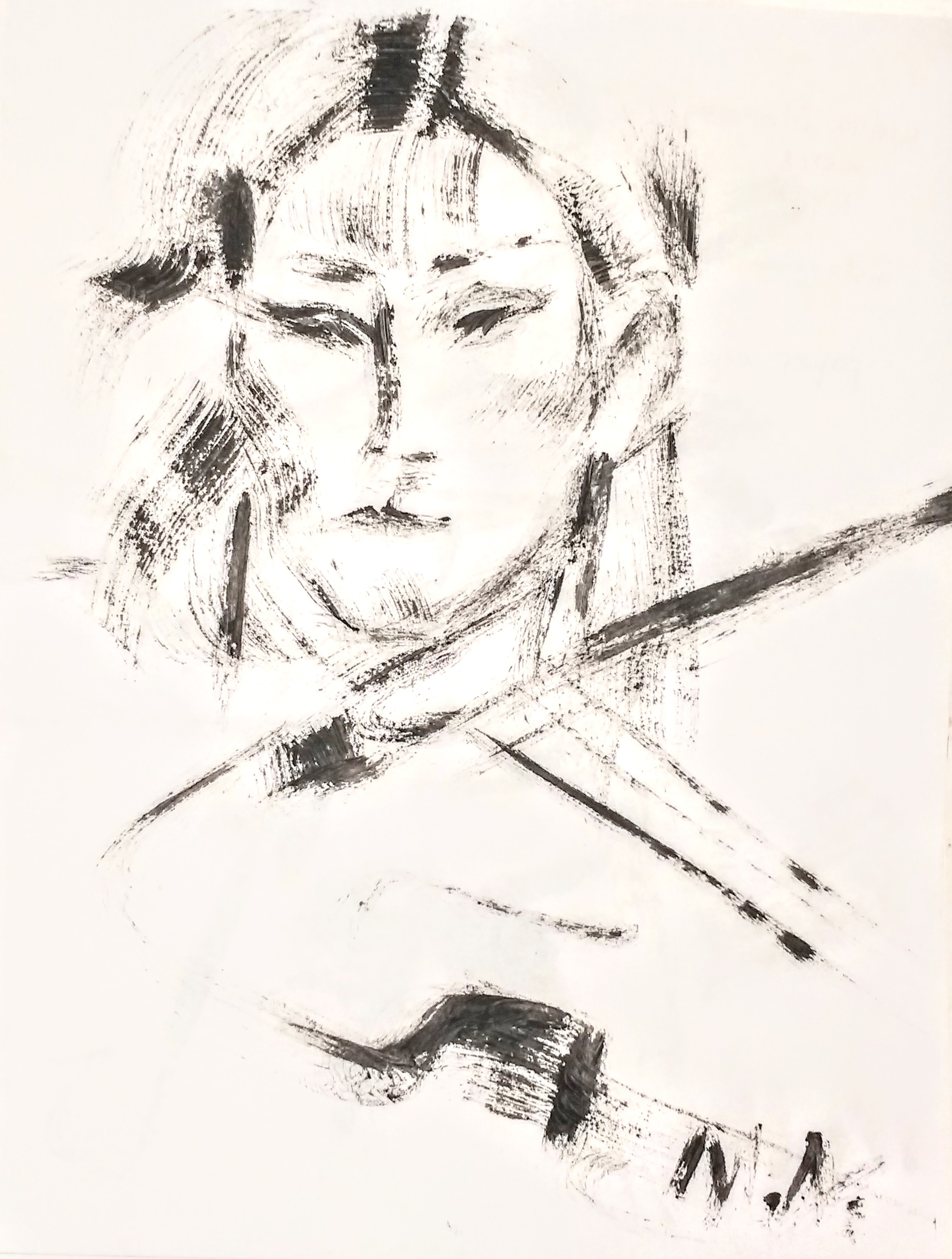

Illustrations by Lidia Moroz

Jazz. This large, amorphous, flexible, strange, constructed, improvisational, musical animal breathes life into New York City with a constantly changing scene and a rotating cast of characters. I’ve always been interested in it from the time my brother played Charlie Parker to me when I was just 5 years old. From that first moment, I’ve been exploring as many versions of the genre as possible. Here’s what I heard playing over the past few weeks.

New York has a vibrant and diverse scene for jazz music. Whether it’s a famous stage in the West Village or an art gallery in the Lower East Side, there are always notes boppin’ through these blue streets.

Through a friend, I heard of a free jazz concert going on in a venue known as The Clemente. The concert series is titled Justice is Compassion. I saw two ensembles there. The first group consisted of Daro Behroozi, Alexis Marcelo, Daniel Carter, Dan Kurfirst, and Leonid Galaganov. The second ensemble was Sana Nagano, Ken Filiano, Peter Apfelbaum, Max Jaffe, and Keisuke Matsuno.

The first session starts as patrons slowly begin to fill the space, an open floor with some folding chairs. From the back of the room emerges a line of sounds followed by the musicians creating them. The music of shakers, hand drums, and gongs fill the room while a trumpet lets out a somber tone. The musicians take their place at the front of the room where two drum sets, a piano, a few pieces of tarnished brass and silver, are ready to be played and heard.

Daniel Carter blows through a muted trumpet. The keys tickle sensory perceptions while fingers softly tap on hand drums and a mallet bangs a gong. A portrait resembling the trumpeter hangs on the wall behind the percussionists. Flanking the image are two abstract charcoal paintings.

The drummer plays a tiny cymbal with a violin bow. A silver sax rumbles along with what feels like traditional hi-hats amidst wonderful cacophonous sounds.

The open front of the piano shows hammers hitting strings as the Alexis Marcelo slides his fingers generating wild rhythms. The vocal moaning of saxophones entices a crowd of hushed and hunched New Yorkers to occupy the edge of their seats. A sudden break. The piano bangs out melodies familiar and experimental. The drummers link eyes and hammer wildly on anything they can reach with their sticks.

The performance ends much like it began. The percussionists slowly walk around with hand drums and gongs. The prolific Daniel Carter blows one long somber note on an alto sax. Eventually the crowd takes a breath in unison as the musicians let their bodies rest. Then applause.

The second performance was slightly less experimental in its stage presence. The musicians took the stage and tuned their instruments. Sana Nagano holds a violin plugged into a peddle board. Ken Filiano stands in the back with an upright bass and eyebrows like the grandfather from The Munsters. Peter Apfelbaum sports a fedora and a saxophone. Keisuke Matsuno siths with an electric guitar resting on his lap. And last but not least, Max Jaffe sits behind a traditional drum set.

This performance had some elements of jazz standards, but was evidently infused with improvisations. There was an elegant orchestration of sounds clearly conducted by the violinist, who had composed all the pieces played. Nagano used the peddleboard to make her violin speak Japanese at one point. Matsuno applied some interesting distortion effects throughout. It was by far one of the most incredible manipulations of sound I have ever seen.

Max Jaffe made the wildest facial expressions during his performance, a crucial element to the show. Matsuno jammed so hard that he broke a string. Apfelbaum took a shot at a cowbell solo, and was remarkably good! Filiano counted wildly throughout each song. This was one of the most interesting performances I have ever attended in my life.

I found amongst the crowd a person who was illustrating the scene with nothing but mascara and paper. These are the images that run throughout the piece. Her name is Lidia Moroz and she can be found on Instagram here. She was invited to the concert by one of the musicians who was performing. She does sketches of everything that impresses her with any available media. The musicians impressed her a lot. She was inspired by watching them play and listening to their improvisation. Sketching is her way to feel the music, to understand and express the emotions it evokes. She wrote to me after the show, “It is interesting to make an art action during another art action, it is a double energy and it feels a bit risky as well. It’s the most plural interaction with other kinds of art.” All the artworks have been gifted to the musicians.

Luckily, I was able to meet Daniel Kurfirst after the show. He was one of the drummers for the first ensemble. We shared correspondence where he kindly answered all of my questions:

Greg Stewart: Can you tell me a bit about the modern state of jazz in New York? In your opinion, where do you think the best jazz happens?

Dan Kurfirst: The “Jazz” umbrella encompasses so many different things now that may appear only loosely related to each other. For the layperson, an evening at Blue Note compared to an evening at Vision Festival, it might seem like these musics hardly, hardly have anything in common with each other. In my opinion there is a definite connection which goes back to the SPIRIT or ESSENCE of what was happening in New Orleans in the early 20th century, and of course all the way back to West Africa where many of the musical concepts came with the people who were brought here as captives. It’s a certain creative attitude. The music of William Parker, Wynton Marsalis and Jelly Roll Morton etc. All have this in common, even if the outward form of the music might be very different.

It’s very important to note that many musicians don’t particularly like the term Jazz if not outright rejecting it. The word has a lot of negative connotations for a lot of people. I’m not sure if I have a better label, but Improvised Music, Black Music, Black American Music might do the job better than Jazz.

As to your question, I think NYC is still the jazz capital of the world – there is something about the energy of this place that draws top creative talent from all over the world – people give their lives for this music and most of them want to be here, so what can happen here creatively is really pretty remarkable. My personal opinion, I think Arts for Art is doing a phenomenal job at preserving, innovating and presenting the music. But objectively, there are many fantastic institutions like Smalls, Lincoln Center, Jazz Gallery…they all tend to specialize in a different niche within the music.

GS: How do you feel about the classic jazz venues of New York such as Blue Note, Smalls, and Birdland?

DK: That is not really my scene so I can’t comment first hand – I have seen wonderful performances at Blue note and Birdland many times in my life, and I have friends who love the smalls scene and value immensely what the jam session and community has done for them. So from my vantage point it seems like they are all doing a fine job, but I’m not involved so much to make a really sophisticated judgement

GS: Can you speak a bit about the process of improvisation and its role in jazz?

DK: Improvisation is at the heart of this music and where it gets most of its character, I would say. There are many different approaches to improvising and that is a large part of what distinguishes the different styles of music that I outlined a little bit in response to your first question. For instance, in be-bop, a soloist generally improvises over pre-determined chord changes within the form (a set number of bars), and there are various theories about how best to work within that. Many musicians find tremendous creative freedom in staying within the discipline of a form like this. At the furthest end of the spectrum would be “just play” – certain styles of “free jazz” have no preconceived rules or limitations on what any musician can do. In between that, there are situations that don’t have chord changes or traditional forms, but where an improvisation might be bound by other concepts – modality, rhythm, even verbal or graphical instructions in some settings.

It’s a decidedly not balmy evening in New York. The West Village teems with activity around W 4th Street. Students, tourists, and lifetime city folk bustle through the streets. Bodies wrapped in coats, scarves, and hats pop in and out of restaurants, bars, and homes down on MacDougal Street.

A voice comes over the loudspeaker as the room’s lights dim, “Welcome to The Blue Note!” Joshua Redman and the three musicians in his quartet take the stage. A short introduction begins the performance. The mellow bass line and the slow, melodic saxophone open the set. Melodies roll from the piano like the smooth words of this prolific front man. A soft drumming provides the rhythmic ambience for the rolling notes.

The sounds fly from the sax as if a poet had written them with succinct attention to rhythm and tambour. Low notes ride like a stroll through central park in an early spring day. The bass gets to drive the band for a few blocks around bars using notes to accelerate until eventually the piano jumps back in to help steer them all towards a groovy jam of somber jazz.

Blue Note is the jazz club of movie scenes and every young bebopper’s imagination. This is where everyone gets a chance to express in a specified space of time their understanding of notes on the page. The audience rewards each player with individual applause after their respective solos. Its stage has held the likes of Dizzy Gillespie, Ray Charles, The Modern Jazz Quartet, and Oscar Peterson.

At the end of this jam you can see Joshua Redman say unto his band, “Wow! That was great!” And without hesitation, he jumps into a soliloquy. The sax and the mic feel like lovers whispering sweet nothings in bed.

Joshua takes over the stage with his sound. The other musicians sit and watch like wax figures in Madame Tussaud’s just a few miles north. Until the moment when they all chime in with their respective vocal directions as produced by vibrating strings and skins.

Redman’s quartet consists of himself and his three longtime collaborators: Aaron Goldberg (piano) Rueben Rogers (bass), Gregory Hutchinson (drums).

This is high quality polished jazz. Already deemed one of the most energetic and compassionate, inspired and important jazz musicians of his generation, Joshua Redman clearly takes a planned, coordinated, and clean approach to the genre. This performance speaks to those elements. He is an individual that recognizes and participates in the world of modern/contemporary jazz, as recognized by his cooperation with bands like Soulive and The Bad Plus. However, these are original compositions, heavily practiced and worked for an audience like Blue Note. This is the cream of the crop jazz. You can tell this band has little to no hiccups in their conduction.

Third Street Music School, founded in 1894, is the longest running community music school in the nation. The building it occupies on 11th Street between 2nd and 3rd Avenues in imbued with the professional world of music. While definitely an educational venue, Third Street’s reputation and position in New York City’s musical ecosystem makes it an important and frequent venue for some of the best jazz musicians in the world.

Neal Kirkwood is a composer, pianist, arranger, and band leader. Jazz groups Neal directs range from a trio to a 17-piece big band. The individual who introduced Neal says his reputation has earned him the moniker of “the real deal.” On this evening, Kirkwood is playing piano alongside longtime friend and colleague, Charlie Young. The two performers were college roommates. Young currently leads the Duke Ellington Orchestra.

These illustrious performers open with an arrangement of a song called “Duke’s in Bed”, often considered one of the great album covers of jazz music. There are  Neal and Charlie on piano and sax, with a clearly distinguished presence. Behind them is a string quartet, a bass, and a drummer. The vibe on stage is similar to a classical music performance, with a certain stiffness, a practiced and professional attentiveness. Clearly, this act is rehearsed, tight, not improvised. Yet, there persists the tonal communication inherent in all jazz. Kirkwood leads throughout the performance. From his bench he points and communicates with his eyes with every player. The first tune has a jumpy rhythm with a playful back and forth between sax, piano, and the string quartet. Melodies swing. The sax sings beautifully. The piano rolls and the strings moan.

Neal and Charlie on piano and sax, with a clearly distinguished presence. Behind them is a string quartet, a bass, and a drummer. The vibe on stage is similar to a classical music performance, with a certain stiffness, a practiced and professional attentiveness. Clearly, this act is rehearsed, tight, not improvised. Yet, there persists the tonal communication inherent in all jazz. Kirkwood leads throughout the performance. From his bench he points and communicates with his eyes with every player. The first tune has a jumpy rhythm with a playful back and forth between sax, piano, and the string quartet. Melodies swing. The sax sings beautifully. The piano rolls and the strings moan.

The second work has a somber, droning tone as the string quartet solos in front of the quiet, attentive band. The piano jumps in as the strings taper out. The master’s fingers gingerly move across the keys. The drum kicks, and the band jumps in. One of the violins solos with a rockin’ bass line behind. The bow-wielding violinist screeches and squeals with precision.

The way Charlie Young stands on stage as he blows his horn is reminiscent of the greats with whom he has worked. A passionate expulsion of blaring jazz. A reverent expression on his face. This man has shared the stage with Ella Fitzgerald, Stevie Wonder, Quincy Jones and more.

Boom pa cha boom pa cha boom pa cha. The drums rhythms flow as the duh duh dun of the piano mixes with the bebop sax and the bum bum bum of the bassist’s plucking fingers. Hi hats clip while feathers shimmy over the snare. Bass kicks as chords hit to hammer strings to form a unique song.

This performance is like actors performing a script. The theatrical nature makes me crave a poetic performance. Each of the instruments a character of a jazz musical. Each voice playing harmoniously to create a story of lives lived by the jazz artists who composed this chorus of notes. Stories of Duke Ellington and Charlie Parker fly through my imagination; fictions of urban life and the founding of something new.

The string quartet leaves the stage. Charlie Young takes center. A distinguished guest of Third Street, this is a chance for him, with the help of Neal, to woo an audience of New Yorkers who all have decided to trek through the cold evening to find a pocket of quality jazz music. With the support of bass and drums, the sax player’s fingers wander through wild valve clicking and cheek blowing.

After our swinging trip through Neal Kirkwood’s interpretations of Duke, he gave us a taste of how contemporary compositions of jazz classical fusion come to life on stage. He stands atop a box and conducts from the front, inviting a different pianist to play; he tells the audience with a chuckle, “I made the piano part too hard, so I had to bring a better player on stage to play it.” A song titled “Octet” rose from a clatter of mallets tapping wooden boxes and high-pitched strings along with a pinging piano and a fury of clacking valves on the sax. This liminal space between contemporary, classical, and jazz is where Third Street Music School thrives.

About the reviewer:

Greg Stewart writes the Around New York column for Ragazine.CC. He was an intern from The New School for Social Research, Autumn Semester 2017. You can read more about him in About Us.

Lidia Moroz is a Ukrainian artist originally from Kiev. She does visual art in painting and graphic and fashion design. She has been studying art since she was a young girl. She had 2 solo exhibitions in Colorado and one in Kiev.

Recent Comments