JACOB MORCH Photo/Unsplash

No Room for Nice White Teachers

When We’re Taking Down the Master’s House

By Jessica Powell and Meredith Sinclair

Over the past decade, the dialogue around education reform has gotten louder, at times acknowledging inequities in our system of schooling. We hear debates about funding and the need for more “high quality teachers.” Sometimes the discourse even acknowledges that schools today are in many places more segregated than they were in the late 1960s.

What this education reform debate fails to address is how white supremacy undergirds our system of education and is in fact the very foundation upon which most institutions in our nation, including the prison industrial complex and our public schools, were built. These two systems in particular, have become so intertwined that a growing body of scholarship and public policy have a name for their intimate relationship and its impact on children of color: the school to prison pipeline.

This discourse, which neglects to see how our system of education is drenched in a living history of white supremacy and perpetuates the opportunity gap (falsely labeled by many as an achievement gap), is largely forwarded by white politicians, education reformers, administrators, and teachers. Our colleagues of color have been speaking this truth clearly for decades. We have failed to listen.

Martin Luther King Jr. in his 1963 “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” urged the “white moderate” to acknowledge how they failed to use their power and privilege to move civil rights forward. He explains:

“First, I must confess that over the last few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizens Council or the Ku Klux Klan, but the white moderate who is more devoted to order than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice….”

Over half a century later, these words continue to resonate. It’s not the white nationalists or Ku Klux Klan members who are in our classrooms forwarding a white supremacist curriculum. It’s the nice white teachers.

These nice white teachers we refer to in this article are the white teachers who see themselves as “doing good” and “saving children from their impoverished lives.” These are teachers who appear kind and often well-intentioned but who lack a critical perspective on their own role in the system and take a paternalistic, savior approach to their work in schools. Sonia Nieto critiques “niceness” as not enough, arguing that being “nice” often means upholding racist systems. These are the white moderates Dr. King urged us to notice, those who prefer “negative peace in the absence of tension.”

Audre Lorde cautioned, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” The nice white teachers (who may view themselves as allies), fail to make any deep change in their students’ lives or in society because they continue to use the master’s tools: white euro-centric curricula and pedagogy and systems of discipline imbued with implicit bias.

This leads us, two white professors of education, to ask, “How can we disrupt the pipeline of nice white teachers?” Beyond the efforts needed to support more teachers of color, we must shift our own curriculum of teacher education to do the following:

- Teachers must develop a profound understanding of the history of white supremacy and how systems of privilege and oppression operate in our society and schools.

- Teachers must begin to locate themselves within these systems of privilege and oppression.

- Teachers must develop strategies and dispositions to disrupt the systems of privilege and oppression.

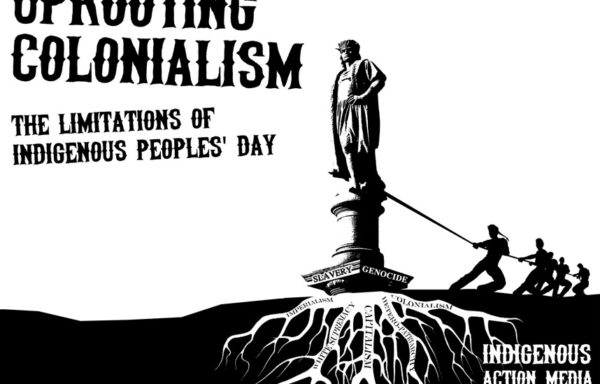

To do so, we acknowledge and build upon the decades of work by scholars and activists of color. This process, which is non-linear and quite messy, can lead aspiring teachers to shift away from the identity of benevolent ally toward becoming accomplices for racial justice. Here we differentiate an ally from an accomplice. Ally teachers are those who fail to take direct action and often choose their own agenda. Building upon the concept of a white co-conspirator or accomplice developed by activists of color such as Indigenous Action Media, Alicia Garza, and Feminista Jones, a teacher accomplice is one who is willing to engage in direct action and take risks.

To do so, we acknowledge and build upon the decades of work by scholars and activists of color. This process, which is non-linear and quite messy, can lead aspiring teachers to shift away from the identity of benevolent ally toward becoming accomplices for racial justice. Here we differentiate an ally from an accomplice. Ally teachers are those who fail to take direct action and often choose their own agenda. Building upon the concept of a white co-conspirator or accomplice developed by activists of color such as Indigenous Action Media, Alicia Garza, and Feminista Jones, a teacher accomplice is one who is willing to engage in direct action and take risks.

As white teacher accomplices, it’s our responsibility to build coalitions with people of color and leverage our own privilege and access to resources in order to take down white supremacy in our lives, communities, and classrooms. In some ways being an accomplice echoes Noel Ignatiev’s stance that “treason to whiteness is loyalty to humanity.” This is not just relevant for white teachers teaching predominantly children of color. It’s for all teachers of all children in all positions and situations.

In our work as teacher educators, we’ve been trying to understand what it looks like to support novice teachers in becoming educator accomplices for racial justice. This means a shift away from a focus on a “teacher toolbox” of snazzy ways to deliver content toward the deliberate centering of culturally responsive, anti-racist pedagogy. The former gets us off the hook in confronting systems of power and oppression; the latter requires seeing the system, seeing where one fits in the system, and developing strategies to fight the system.

Chris Emdin, Columbia University professor and author of For White Folks to Teach in the Hood, describes the dangers of the nice white teacher who carries her white guilt into the classroom, like a giant boulder over her shoulder as she climbs to the top of the mountain. As an ally or white savior she drops that boulder on the heads of her students. Crushing them. In this metaphor, the teacher’s failure to engage in self-critique, nor understand what it means to work in coalition with communities of color and take risks to dismantle white supremacy led to the demise of justice in her classroom.

We must do better. Many of the students entering our teacher education classrooms have been taught a false narrative around justice their whole lives. Most have never had teachers who discussed the concept of privilege or encouraged them to listen, deeply listen, to the stories of the oppressed. Thus, our classrooms are often filled with white aspiring teachers who wonder: “If the narratives of the Black Lives Matter movement were real; if a white supremacist system of schooling was real; if white privilege was real–Why have I never heard of this before? It can’t be real”

This is the challenge for us as teacher educators. We must, over the course of the students’ program of study, help them unlearn master narratives, name their miseducation, and shift toward a curriculum of education that prepares accomplices for racial justice, rather than nice white teachers.

As middle-class, white women who are teaching the next generation of teachers, we must also locate ourselves within this white supremacist system. We must recognize the places we’ve benefited and the places we’ve been complicit. We see the ways we and others have been nice white teachers and have thus upheld the system that oppresses the children we wanted to “save.” We acknowledge that there is a parallel process that occurs as we grapple with our own journey while supporting our students along theirs toward becoming accomplices. This involves risk and vulnerability. Just as we are asking our students to take an ethical stance and see their future classrooms as spaces for direct action, we too must embody this belief. We must create classroom spaces where we (ourselves and our students) feel safe to feel discomfort, cry, ask questions, make mistakes, and feel loved enough to find our way back.

The Trump presidency and the complictiness of so many in our government have unveiled the white supremacy that existed all along. Many of us feel an urgent call to resistance, to become accomplices for racial justice. We see classrooms as a place to engage in this work.

Afrocentric education scholar Mwalimu Shujaa makes a distinction between schooling and education. Teachers can choose to participate in schooling, forwarding a Euro-centric curriculum that tacitly endorses the system as is: replicating oppression and alienation. Or, teachers can choose to engage in education, bringing themselves and their students to consciousness, sowing the seeds of resistance and change, and leading to a new social order.

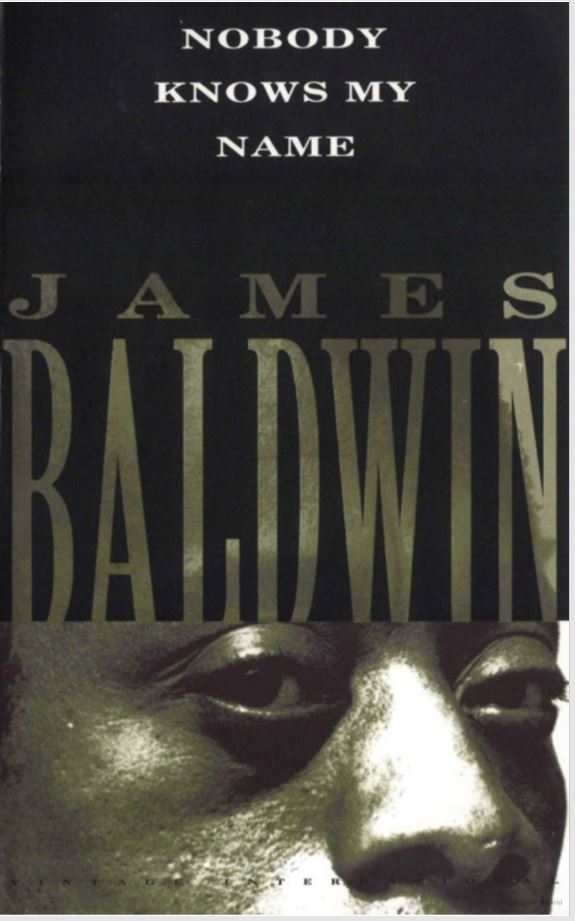

In 1963, James Baldwin wrote, “The paradox of education is precisely this—that as one begins to become conscious one begins to examine the society in which he is being educated.” This consciousness runs counter to the sort of obedient citizens that society wants; however, as Baldwin also notes, obedience to a fault leads to the death of society.

In 1963, James Baldwin wrote, “The paradox of education is precisely this—that as one begins to become conscious one begins to examine the society in which he is being educated.” This consciousness runs counter to the sort of obedient citizens that society wants; however, as Baldwin also notes, obedience to a fault leads to the death of society.

Fifty years on, little has changed. Since our nation’s inception people of color have been systematically oppressed. Today, children of color are more likely to: attend hypersegregated and under-resourced schools; be suspended, expelled, or arrested for minor school infractions; and experience a dehumanizing curriculum where they feel othered and unseen. We intend to break down this system—there is no room for nice white teachers.

Author Bios:

Jessica S. Powell: Jessica S. Powell, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor of Education in the Department of Curriculum & Learning and co-director of the Urban Education Fellows program at Southern Connecticut State University. Her teaching and research interests include culturally responsive and anti-racist pedagogies and social justice issues in education.

Meredith N. Sinclair: Meredith N. Sinclair, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor of English Education in the English Department and co-director of the Urban Education Fellows program at Southern Connecticut State University. Her teaching and research interests include critical, anti-racist pedagogy; adolescent literacy; pre-service teacher education; secondary English curriculum; and young adult literature.

Recent Comments