Marc Vincenz reading his works

***

Marc Vincenz:

“…from the embalmed history to the embedded memory

to the unleashed imagination…”

With Tom Bradley

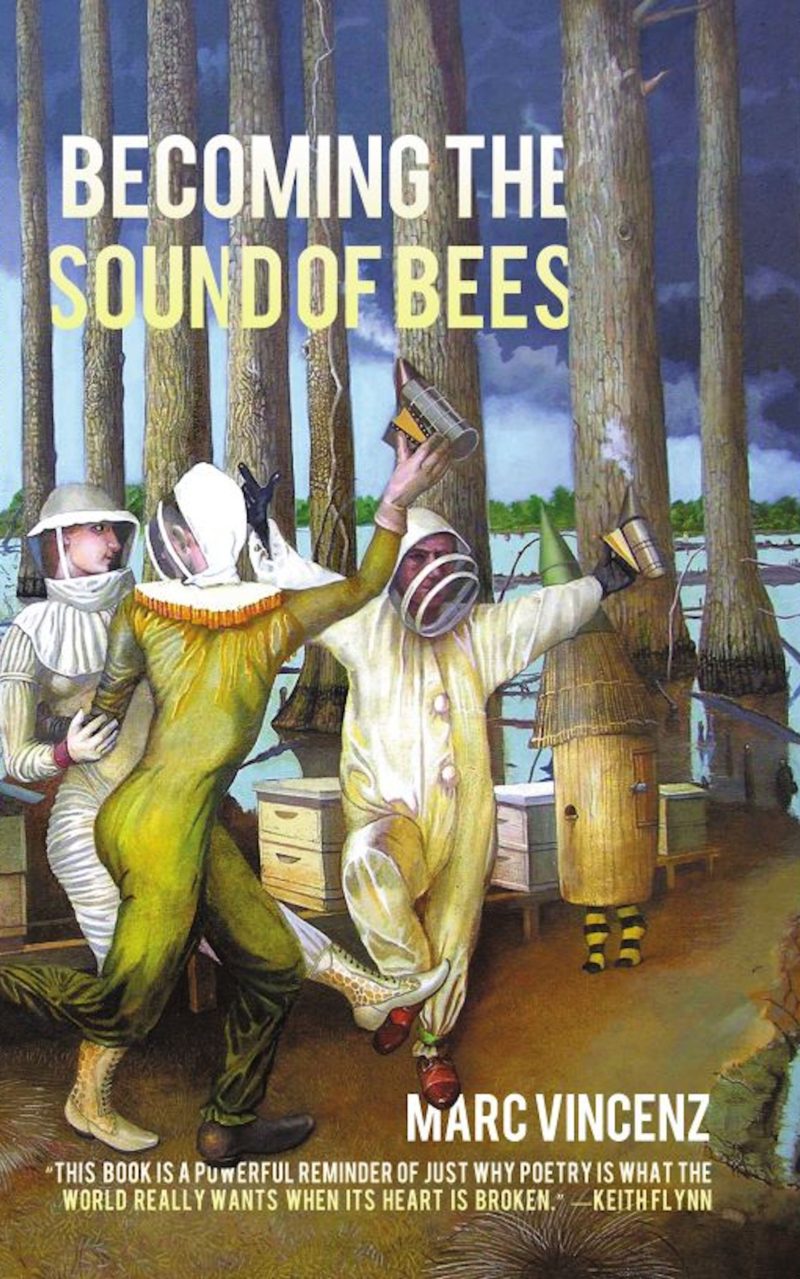

Marc Vincenz is the author of nine poetry books. The latest are This Wasted Land and Its Chymical Illuminations (Lavender Ink, 2015), Becoming the Sound of Bees (Ampersand Books, 2015) and the fully-illustrated, limited edition Sibylline (Ampersand Books, forthcoming). The Washington Independent Review of Books recently said of his work, “Each poem is an open environment where anything can happen, a ceremony of advanced thinking where a pilgrim of great altitudes accepts life’s vagaries.” New Pages called Becoming the Sound of Bees “… a book where doors can fly off in ‘butterflies of rust,’ where poems can stretch themselves sideways across the page, and worlds can build upon themselves in dizzying descriptions. This is a collection for those who enjoy digging their claws into strange landscapes and getting pulled forth by a culmination of sounds.”

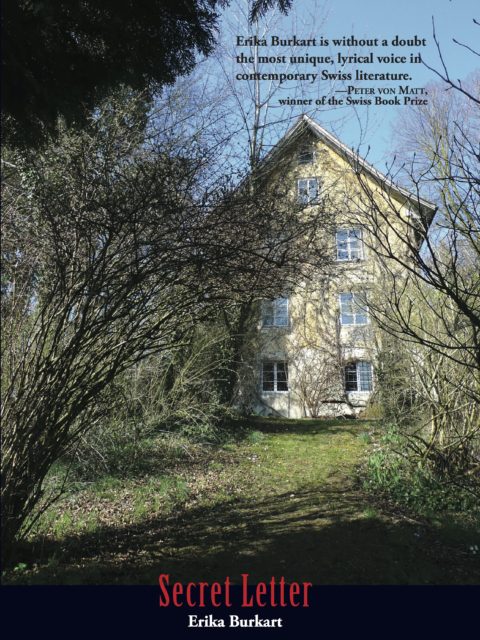

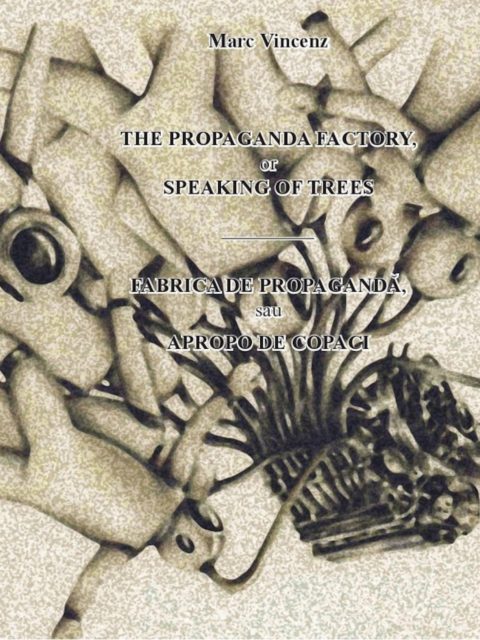

Vincenz is the translator of many German-language poets, including Herman Hesse Prize winner, Klaus Merz, Werner Lutz, Erika Burkart, Alexander Xaver Gwerder, Andreas Neeser, Robert Walser and Jürg Amman. His translation of Klaus Merz’s collection Unexpected Development (Unerwarteter Verlauf, Haymon Verlag, 2013) was a finalist for the 2015 Cliff Becker Book Translation Prize and will be published by White Pine Press in 2018. He has received several grants from the Swiss Arts Council and a fellowship from the Literarisches Colloquium Berlin. His own work has been translated into German, Russian, Romanian, French, Icelandic and Chinese; Bucharest’s Tractus Arte Press released a Romanian translation of his collection The Propaganda Factory at the 2015 Bucharest Book Fair. Among other things, he is International Editor of Plume, Executive Editor of MadHat Press, and Plume Editions, Co-Editor of Fulcrum.

Although he has lived and traveled all over the word, Marc Vincenz now resides, writes, translates and edits in western Massachusetts.

TB: Congratulations, Marc, on your new translation of the great Erika Burkart’s Secret Letter (Cervena Barva). This is your latest in a whole separate career’s worth of translations of German poets: eleven volumes and counting. The Washington Independent Review of Books has called you “a peripatetic linguist … [who] prospers through travel like a psychoactive medicine man.” Aside from psychoactivity (which your own nine collections possess in quantity), the quality that distinguishes your verse is its breadth of subject matter and its command of disparate idioms, far beyond the grasp of most living poets. To what extent can such cosmopolitanness be attributed to your “peripatetically linguistic” renderings of foreign verse?

MV: Language, of course, is not static at all, but fluid, continually appropriating and evolving. When you live as I have done, through extremely diverse cultural landscapes—say for example, from the gagging metropolis of Shanghai one day to the expansive volcanic plains of Iceland the next—you develop a broad view of the world, of language. You become an observer, an accumulator of culture; ideally, absorbing the most illuminating sounds and visions from each of the places you set your bag down. There is a moment, after all this wandering, when something coalesces in that vast array of voices and images. They come together in your mind as one, and somehow the world becomes easier to listen to, to silently observe. Language itself becomes easier to absorb. At least, that is my experience of it.

Though I have predominately translated German-language writers into English, I recently began a new project in collaboration with Bucharest-based poet Marius Surleac, translating several contemporary poets from the Romanian. Three of these translations of Ion Monoran’s poems just appeared in Solstice Literary Magazine (http://solsticelitmag.org/content/three-poems-2/). I also have an exciting French-language translation project in the wings. Does my international upbringing have something to do with my affinity of/for other languages and cultures? Most certainly—it’s a passion, Tom. Do I feel comfortable in a wide array of places and sounds? Yes, absolutely. It was entirely the way I grew up—slipping in and out “peripatetically” from place to place, from tongue to tongue. It was somewhere after I arrived in the US in the early eighties that a light bulb came on in my head. I knew that I had to dedicate myself to the written word.

Of course, I am occasionally befuddled by the striking differences in languages, words or expressions that on the surface appear to be untranslatable from one to another. Often, the approach in cases like these is to avoid the literal, but root around in the cultural context. In my experience, (perhaps with the exception of those social groups living on the margins of the world who have resisted modernization), there are few instances of languages lacking a parallel in each other’s cultural symbolism. Although linguistically these acts or descriptions may be expressed quite differently, there always seems to be a way to represent almost the same experience in the target idiom. When working with Language, absurdist or concrete poetry, however, from time to time you will be entirely stumped. In these cases, for the most part you rely on your melodic ear and intuition.

For example, when comparing the German and English literary language, it was the Swiss poet and novelist Ernst Halter (Erika Burkart’s husband) who said that he perceived German as more of an internal language, a language that attempts to symbolize what goes on in the mind, whereas English is more concerned with the outside world. I am still giving his proposition some serious thought.

TB: Can you cite an example of a word or expression that proves difficult to translate into English, perhaps from the German?

MV: Oh there are many, but for example, the German noun for something approximating “a walk,” Spaziergang, for example, means more than the English “a walk” or “a stroll”. Potentially, the archaic English word, “a constitutional” is a more fitting parallel. spazieren, the verb, differentiates itself from gehen (“to go” or “to move”) which is more commonly used for the English “to walk”.

In an attempt to get some kind of cultural perspective, let’s look at this etymologically. Spazieren comes from the fifteenth-century Italian, spaziare, which means something more like “to spread oneself out” or “to let oneself go”. The second compound of the word, “Gang” possibly originates from the Sanskrit jangar (meaning “shank”—as in the ankle), but is represented in old Norse as gangur and old English as gang, meaning “a passage” or “a journey”. (Consider the word “Gangway,” still in usage.) Out of the modern cultural context, the word therefore means something like “a liberating passage or journey”—which, of course, makes sense given that the Spaziergang became popular in the eighteenth century among the elite, who would take strolls along the river or through the park or along the promenade to take in the air—a meditative, perhaps spiritually healing activity. And it is obvious that to translate the entire message encapsulated in the German would, in most cases, not be suitable in the modern English idiom. So, depending on context, we settle for “a stroll” or “a walk”; this could be further clarified by saying: “a meditative stroll” or “a walk to clear the head.” Either way, the word Spaziergang implies that there is a meaning of sorts attached to that passage of time on foot. It’s all in the intention.

I discussed this very word with my fellow translators at a conference some years ago and was surprised to find out that there is no noun equivalent to a Spaziergang in several languages (in some, apparently, even the cultural concept of “taking a walk” does not truly exist).

TB: And what of your own poetry? How has your international exposure influenced your work?

MV: Naturally each locale has its own fragrances, its own cultural quirks, mythology, architecture, landscape, customs, politics—and yet, all of these are mirrors of another culture: different ways of expressing (symbolizing) the same things. Humanity, after all, is human—desires and needs are much the same the world over. Imagination and innovation is a constant. It is my firm belief that inference and foresight are at the heart of human language. Likely this is the reason why poetry has such an important role in my life.

Something from everywhere I have laid down tracks has wormed its way into my writing. And, in that sense, I suppose you might say that much of my writing is about place—or to put it more succinctly, about defining space. Becoming the Sound of Bees and my newest collection, Unspeakable Desires, are set in mythical lands—or lands of the wandering mind, if you will. These mythical lands are assemblages of many cultures. Spaces that appear to be specific are not obviously contextualized; allusions to figures out of history or entirely out of the realm of the subconscious (forests, mountains and oceans) materialize from out of the possible past or potential future. Little is as it appears on the surface. These are reflections of many eyes and tongues, many senses—real or imagined. They are attempts at the discovery of a common thread or vibration that carries through most known and imagined worlds. It seems to me that by stepping outside the every day or very familiar and placing it somewhere new—an assemblage or clustering (as if around a cell or an atom)—that the most captivating thoughts become less obscured. Don’t you think that it is in the universality of a mythological narrative that the most profound discoveries are to be made?

TB: Possibly. But, in my own work, I avoid thinking explicitly in terms of “myth.” The notion has been debased by Harry Potterism and Superhero movies. If a piece if literature deserves the term “mythic” in the profound sense, it can be set in a so-called “realistic” world, or a fantastic. At the level where myths are made, either type of setting is essentially the same, as you just suggested. Can you give me an analogy of that “sameness” of culture you were referring to?

MV: When I talk of mythological narrative, I am not referring to specific icons or symbols plucked directly from ancient traditions: Greek, Roman, Chinese or Mayan. I am responding to an approach in storytelling (mythmaking) that humans have used to explain their visions through time—a universal measure to imagine or envision worlds beyond our own reality; a method to explain or decode the unexplained or the past. Myths transform, shift and deform over time—along with the language that carries them; stories change, shift and adapt, symbols take on new meanings. A recent example of a stunning work of fiction that tackles this subject on some level is Will Self’s novel, The Book of Dave, or less recently, Walter M Miller’s fantasy novel, A Canticle for Leibowitz.

OK, regarding that analogy of cultural parallelism, let’s go with one of my favorites: food. The delicacies of a specific region might be a feasible analogy of how an “internal” culture is reflected on the outside. For example, rice (that cereal grain which now feeds a lion’s share of the planet) and the varied manners in which it is prepared, from Rome to Valencia to Guangzhou to Delhi, may be an illustration of how cultures mirror each other. In that order, we have risotto, paella, fried rice and biryani. Despite their varied local flavors, are these not all derivatives of the same original recipe? The Ur-recipe, if you will.

It may well be that the first recipe originated in China (where scientists believe rice was first cultivated), and this spread to India, then Italy and Spain—possibly by way of the Silk Road. Or, it may be that (as has been surmised with the invention of writing, or the invention of the wheel) that these recipes underwent independent evolutions, in different parts of the world simultaneously and it just the very nature of humanity that they develop down similar paths. Either way, if we are to believe our scientists, at some stage rice had to make it from the cultivated fields of Guangzhou to the market stalls of Valencia. And, bless the stars, a good paella is a thing of beauty.

Of course, you can only ever see a portion of a thing—never its totality in the moment of observation. Surely it follows then, that we only ever have partial answers; and, if they are partial answers, they cannot be complete truths—just stabs in the dark, rice kernels of reality, that’s all.

TB: So how does this continual up-rooting, this constant changing of locale, effect your own work?

MV: Traces of diverse mythologies or cultural symbols creep into your every day, into your sense-field; smatterings of music and snatches of landscapes too. A poem may arise with a visualization or it may make itself known sonically through an opening line, a mental image or a melody that leads the rest of the poem musically or imagistically. So, sound, cadence and tone (the singsong resonance of a particular tongue) finds its way through the tiniest of crevices. And the most vibrant visuals too: from the street stalls of Asia to the jungles of South America to the mountain landscapes of the Alps.

Quite often, while working on a poem, I’ll find myself transported to one of these distant locales. When there in your mind’s eye, you can’t help by become enchanted with the feast of senses. More often than not, I allow these senses to come through and reflect themselves in the poem. Occasionally they lead down dead end roads, but mostly they are loyal companions on my literary journey. Over time, I find it easier to tap into these other worlds—even sitting in a café in the middle of New York City. And strangely, at least for me, it is probably the most effective to dream up a world at the polar-end of the place you find yourself in that particular moment.

And then, there are the voices too: the wide-eyed calls of the fish merchants, the saber-rattling of the lager louts and the soccer supporters, the Latinate incantations of the Benedictine monks or the karmic chants of the Buddhist lamas, the uninterrupted swell and sway of the oceans and the squawk of the seabirds … there is no end to the marvelous palette of sounds and colors—not enough words and phrases and time to bring them all together.

As you know, I was brought up a wanderer. It is in my blood, no matter where I find myself, and so, in the course of my writings, I drift and delve—from the embalmed history to the embedded memory to the unleashed imagination, which is, of course, a reflection of memory too. Even a mirror is a reflection of itself.

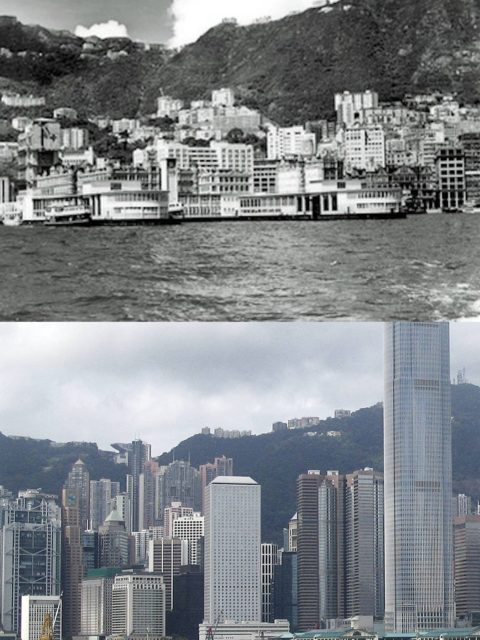

TB: To call you a wanderer is putting it mildly. You’re only poetically peripatetic, but your corporeal moiety has been around the block a few times as well: nativity in Hong Kong; adolescence in a Swiss monastery; varsity hijinks in the USA; adult residence in Spain and The People’s Republic of China; sojourn in Iceland. Does this universality somehow account for the impressive array of languages into which you have been deemed, and proven, eminently translatable? Also, These qualities in your work lead me to suspect that you were brought up in at least a bi-, if not multilingual household. How many tongues lashed your developing ears?

MV: I was brought up in a household that spoke three main languages: English, German and Rhetoromanish. On top of that, since early childhood (having been born in Hong Kong), I had the sounds of Cantonese and Mandarin clanking in my head. As a small child in the 1960s and ’70s, I played and scrapped with the children of the market stall owners of Hong Kong’s Stanley Market and spoke fluent Cantonese. But my father worked with people from all over the world, and thus I grew up in a home that never had less than five languages careening around at any one time.

In a sense, I’ve been translating all my life. My mother is British and my father was Swiss, a country lad from a small mountain village. My father’s mother tongue was Romanish, or more specifically, Rhetoromanish (Romantsch Sursilvan, a direct descendent of the language spoken in the Roman Empire with a handful of Celtic words tossed in the mix—only around 20,000 people speak it); but, like much of Switzerland, he grew up multilingual: German being his second language; Italian, third; French, fourth. He was taught English in high school, but by the time I was born, he barely had a trace of Swiss accent.

The Benedictine Monastery in Disentis, The Grisons, Switzerland where Vincenz studied from the ages of 12 – 16

TB: When talking of Romans and Celts, one of the poems from your collection Becoming the Sound of Bees comes to mind—“Old Country”.

On Sundays before she rises to the murmur

of ancient god-call, before a thousand pilgrims

plummet, cows graze uphill against the grain.

& as mountain swelters in shadow, the last lynx

growls in the trees. Gion and Gulio guzzle beer

hot, even in the swell of lukewarm summer.

In this hidden valley night crawls slow, here you

find the lost snow of Caesars, the pit that held

a hundred angry Celts roaring at shin-yapping hounds,

bleeding spikes thick as arm-wrestlers. He enters

the shrubbery pelted, without a single thought

for blood, but for lichens & wild crowberries.

She turns to face him in the dark earth

of her precious skin, a fine golden weed of hair

like Cassandra, & asks him to let the wolves in.

TB: Was this poem somehow inspired by your father’s Romanish heritage? And how about your mother?

MV: Yes, there are references there: the locale, the mountains, Gion and Gulio guzzling lukewarm beer (regular customers at my aunt’s restaurant in Switzerland—every morning they would ask her to warm the beer up in a pot), and that lost snow of Caesars (locked in the valleys—as was language itself).

My mother’s parents were Cockney Londoners. After the turmoil of the Second World War, my mother’s father took his family of three—my mother, grandmother and himself—to live in the Pearl of the Orient, Hong Kong. Mum was five years old when she arrived in Whampoa Harbor on a passenger ship from Portsmouth and was exposed to the multicultural center of Asia, which was then British Hong Kong. She speaks English, a smattering of French, Cantonese (enough to get by in the markets and street stalls ) but somehow, she never got along with German. At one stage she learned Romanish, and apparently, one summer in Switzerland actually managed to hold simple conversations, but it never really stuck. So, we always spoke English in our home. It remained our staple whether we lived in Hong Kong, Switzerland, Spain, England or the United States. My father and I would sometimes speak German, occasionally Swiss-German (when we wanted to be certain no one could understand), and as I had said previously, there were always several other languages floating around on any given week. Later, in the various schools I attended, I was forced to learn Swiss-German (quite different from the standardized “high” German), Latin, French; later still, Italian, Spanish, Swedish, Icelandic, Mandarin.

Literary translation is something I began much later, on a whim really. It was when I lived in Iceland and stumbled across a book of German poetry in the Reykjavik Library. It was a collection by the Swiss poet, Erica Burkart. I took the book home, and almost automatically, without thinking, began to translate them into English. The whole translation process seemed completely natural to me—very similar to writing my own work, only I was fine-tuning my ear to another voice, another narrative that wasn’t specific to me. On some level I had always been doing that.

TB: So then, would you say your writing has been influenced by the works you have translated?

MV: Certainly. But not by way of direct imitation. Erika Burkart, for example, and her husband, the poet Ernst Halter, taught me quite a bit about observing detail in nature—or more specifically, a unique way of looking at nature as a language, a mythological, coded language, that—in her case—the poet spent a lifetime attempting to decipher.

Two other Swiss poets, Klaus Merz and Werner Lutz, both taught me about the short form. Much of their poetry lives within the boundaries of four or five lines. Inspired by my translations of their work, I dove deep into the fantastic world of the haiku, of the Zen poets and the ancient Chinese work of Li Po and Du Fu, the gushi forms.

As you know, there are many voices in my own writing—so the translation work seems a natural extension of what I do. At a certain point, the translation becomes your own work. The narrative is still someone else’s, but, much as an instrumentalist interprets a melody, the new words in your own language become part of your personal glossary.

A couple of years ago, the Zurich-based press, Wolfbach Verlag, brought out a bilingual poetry collection of mine translated into the German by Swiss professor of English literature, André Erhard, Additional Breathing Exercises / Zusätzliche Atemübungen. The translation took around a year and a half to complete and I worked very closely with André and the editor of the publishing house, Markus Bundi. Experiencing translation from the other side of the German language taught me much about my own writing and the blood, sweat and tears of deciphering cultural symbols. André, Markus and I spent several day-long sessions arguing over poetry and wine.

TB: The great Helena Petrovna Blavatsky could with equal ease have written her books and spread her evangel in Russian, French, German or sacerdotal Senzar, but, seeing how the USA was burgeoning in her day, she foresaw that English would long be the lingua franca, so chose that. Why do you choose English for most of your poetry?

MV: The fact of the matter, Tom, is that English was and remains my mother tongue. It was the main language we spoke at home, and aside from my time at the Benedictine monastery (ages twelve to sixteen), the majority of my education was in the English language. I feel comfortable translating into the English from many tongues—however, the other way around? No. I don’t believe my written German is on a literary level. Good enough for family correspondence, but not for writing poetry or philosophy.

MV: The fact of the matter, Tom, is that English was and remains my mother tongue. It was the main language we spoke at home, and aside from my time at the Benedictine monastery (ages twelve to sixteen), the majority of my education was in the English language. I feel comfortable translating into the English from many tongues—however, the other way around? No. I don’t believe my written German is on a literary level. Good enough for family correspondence, but not for writing poetry or philosophy.

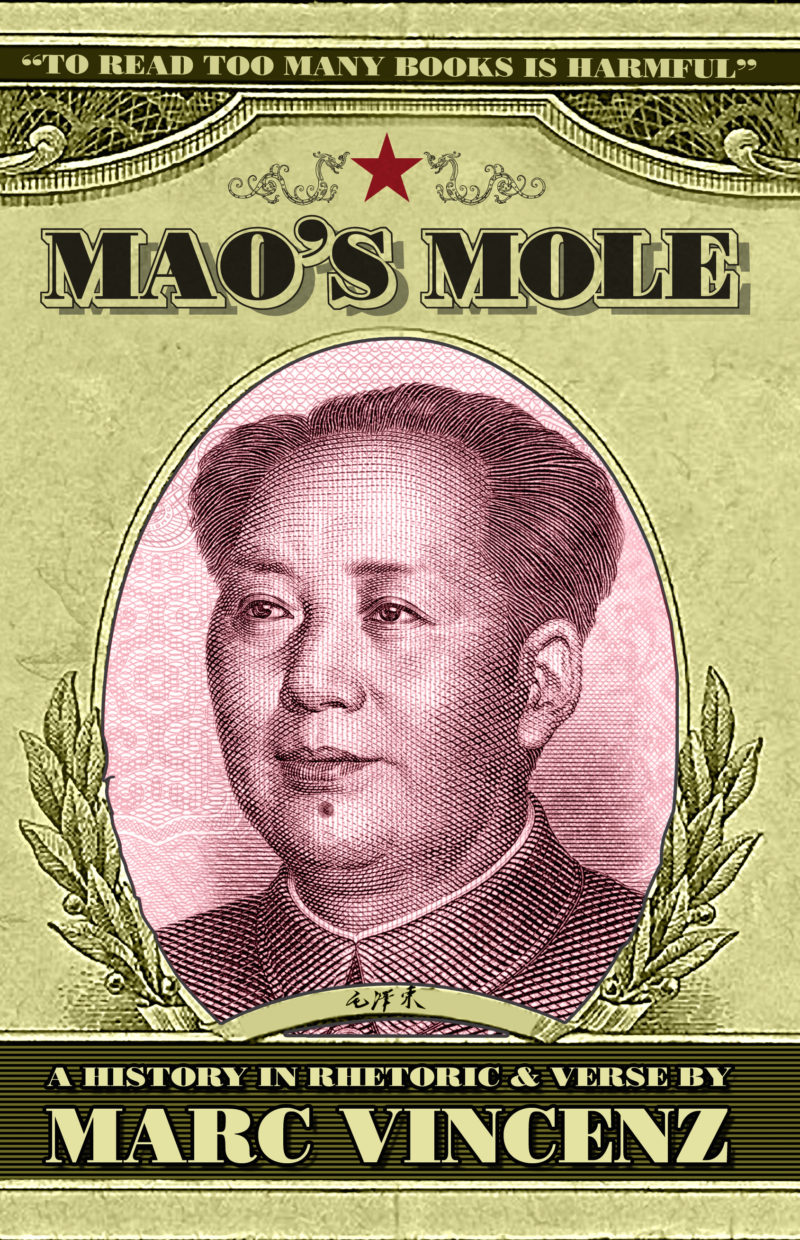

TB: Not surprisingly, your books are set in ever-distorting, metamorphosing landscapes, sometimes sheerly fanciful, often composites. The one exception is Mao’s Mole. The famous phrase, “Live a week in the Middle Kingdom, write a book. Live a month, write an article. Live a year, write nothing,” clearly does not apply to you. What is it about the world’s oldest, hugest civilization that compelled you to place an entire book within its boundaries?

MV: The years living in China—over ten of them, I resided in the bustling city of Shanghai. I traveled far and wide across the Middle Kingdom. I even had the chance to visit that fabled city of Lhasa in Tibet and walk those thousand steps or so to the Potala Palace where once the Dalai Lama resided.

Despite having grown up in Hong Kong and my father’s business dealings with the communist Chinese government of the sixties, seventies and eighties, I had always lived at a distance from China proper, that elusive kingdom behind the bamboo curtain. When my father went on his business trips, be would often be gone for weeks on end. (In those days you could only communicate with China via telegraph or the very occasional telephone call—according to Dad, you had to fill out a form with the content of your message, which first needed approval from the appropriate government body. He once attempted to make a call to his father in Switzerland and wrote on the form that he would be speaking in Romanish. The call was not permitted.) When he returned, normally utterly exhausted, he would recount to my sister and I the wild and fanciful tales of what went on in that elusive, impenetrable Kingdom of Mao. You must understand that very very few foreigners had actually visited China during that era. Nixon didn’t even get there until 1972.

I guess there was always something urging me back. Some part of me wanted to try and comprehend what this place, a place that I had been surrounded by as a child, truly was; to fill in the blanks, so to speak. I learned my lesson the hard way.

In the nineties, I moved to China to begin a fateful business cooperation with a Jiangsu native. The next ten years were probably the wildest, craziest of my life. Over that period we built a small empire in industrial design, manufacturing, exporting all manner of goods from China to Europe, then later to the US. At one stage, we employed somewhere close to two thousand people: factories in Jiangsu, Zhejiang and Guangdong provinces, a massive logistic center, two hundred or so working in our Shanghai head offices, including a sales and marketing team of expats from all over the world. Over twenty languages were spoken in the office—from Ukrainian to Tagalog, from Hindi to Norwegian.

It was nearly the end of me. On so many levels it was wrong—the exploitation of cheap labor, the manufacturing of substandard products, the layers and levels of cronyism and corruption. Naively, we believed we might do some good, we might be able to influence the world—and China in a small positive way. We followed the strictest, most balanced policies of employment, took care of our staff and their families as best we could, invested in locals, in their culture, in their art and craft. We attempted to do non-profit work, helping in further education and so forth. Over the years, we tangled with bureaucrats, argued with crooked judges and government officials, fended off dishonest businessmen and their cronies, and dodged the sharp knives of organized crime (which spins its deadly web through much of the PRC). These nerve-wracking encounters occurred virtually on a daily basis.

It was a nightmare, Tom. And yet, life was so varied and rich. Shanghai in the nineties seemed like cocaine-fueled Boomtown—the horizon transformed on a daily basis. For the first few years we lived in the same apartment on the Old Concession side of Shanghai, not too far away from the Bund. In the space of those few years, the simple hardware market across the road miraculously transformed into a beautifully manicured park with little paddle boats, later a textile market, then a shopping mall (which was never occupied), and finally into to a megalithic high-rise that eventually blocked out the daylight and the ever-yellowing horizon.

MV: There was scarcely a day when you didn’t experience something wildly new and exciting. On so many levels, there were—and are—no limits. But China was and still is most assuredly a totalitarian state; in many ways (despite what much of the business media intimates), no different from the oppressive regimes of Myanmar, even North Korea. In other ways, though—the way, for example, that the culture of the Taoists and the Confucians and the Buddhists has merged with Mao’s ludicrous interpretation of Marxism and the now-appropriated “capitalist” ethic espoused by the “to-get-rich-is-glorious” Deng Xiao Peng—utterly fascinating. Fascinating as a study in humanity, horrifying as a study in humanity. Every day was a challenge and an illumination: part nightmare, part delicious dream.

Living there, you can’t help but admire: zhongyao xue, the ancient art of herbology; the skills of acupuncture and acupressure; the craft of cloisonné and lacquer; the intricate designs of the jade sculptors; the steady hand of the Ming Dynasty furniture-makers; the serene pagodas rising above smoggy cityscapes; the untold varieties of cuisine—from the noodle-makers of Beijing to the duck-roasters of Guangzhou. It seems there is no limit to the diversity of art, craft, design and human ingenuity. And yet, despite the mute presence of the ancients, there is an ultra-modern, perhaps naïve ignorance hovering over all that makes China a wondrous civilization today. As you know, much of the past remains hushed or unspoken.

The follies of Mao and his cronies have long been brushed under the carpet. Many of those old enough to remember have quickly forgotten, and the youth of today embrace Nike (apparently, China is now the US company’s biggest growing market) and McDonalds and their own equivalents, Tsingtao Beer or Haier, just as they embrace the figure of Mao Zedong as an icon of the iron will of its (for the most part—at least in my experience) highly nationalistic people. Any mention of the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre, however is either met with restrained whispers or some kind of collective amnesia. Nobel Peace Prize winner, Liu Xiaobo, in the introduction to his poetry collection, June Fourth Elegies, referred to it thus: “China—whose experiences of suffering and national absurdities are rare in the world—till today has yet to undergo a process of wakening and repentance, but instead intensifies its flashy bubble of prosperity coupled with a vain servility.”

120-ft Gold Statue of Mao erected January 2016 in Henan Province – now demolished under orders of the central government. Credit: AFP/JIJI

Another telling figure of the shape of “modernizing” China is the number of plastic surgeries conducted. The pursuit of beauty is quickly becoming a national obsession. According to the BBC, in 2014 over seven million people had plastic surgery performed on them (a market that is now valued at over sixty billion dollars). That is still less than half of the cases performed in the US, but considering that many of these clinics (officially over 10,000) have only existed a handful of years (and many more are black market and thus under the radar), that is dumbfounding. China is now the third largest beauty-enhancement market in the world, after the US and Brazil!

Then there is the censoring.

I recall an issue of TIME magazine around 2005 or 2006 that I happened to purchase in the bookstore of a Hilton Hotel where an article on the current state of the Middle Kingdom had been manually blacked out with magic marker. Every copy was the same—and so, I assumed that somewhere there was a team in a warehouse removing any conspicuous text from any foreign publication. As you well know, Tom, to this very day Facebook remains blocked; You Tube and Twitter too. And, it’s getting worse. TIME recently reported that this very year the government released a new “eight-page catalog of forbidden subjects” for TV programs. “Chinese censors also nixed programming that glorifies colonialism, ethnic wars and dynastic conquests of other countries. TV shows must not, under any condition, undermine social stability.”

As of 2014, all Internet content is regulated by the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) and the Office of the Central Leading Group for Cyberspace Affairs. Talk about the Great Firewall of China—you won’t believe it but the CAC actually wrote a song that promotes internet censorship and entered it on some statewide talent show. Doesn’t that sound like something out of Huxley’s Brave New World?

TB: Yes, it does. During my years there I managed to get into a few so-called “closed cities,” and met a handful of dissidents who spoke in guarded whispers. What are your experiences in that department?

MV: When you travel—in particular into the less-populated, poorer regions toward the interior—you come to realize the damage that Mao and his Cultural Revolution have inflicted; the brainwashing of the generations that came of age from 1950 until now. Yes, of course there are non-believers; there are thousands of activists and religious refugees—mostly hiding beneath the surface.

For example, did you know that the government appoints the head of the official Chinese Roman Catholic church? That those who see the Pope as the pontiff are forced to secretly conduct mass in basements and abandoned warehouses in the dead of night?

TB: Yeah, it’s a very big deal for believers, the apostolic succession and so forth. My wife, who is Popish and has dark hair and darkish skin, got herself smuggled into a couple of those masses. I could not believe they took the chance. She was moved by the experience.

MV: The same applies to those who wish to practice Islam or Tibetan Buddhism according to their own perceptions. At one stage, merely possessing an image of the fourteenth Dalai Lama was grounds for immediate arrest. Then there is the case of the Falun Gong, a peaceful reimagining of Buddhism with an intense Qigong practice, who, since 1998, have been gathered up and imprisoned in droves. The Communist party only sanctions five official religions—all controlled by an iron fist in Beijing.

Human rights?

The PRC has no freedom of speech, no freedom to practice religion, no human rights except the right to get rich. Make as much money as you want, but don’t criticize, don’t push the boundaries of society. How could anyone with a modicum of ethics do business under that premise?

Human rights?

Ask Liu Xiaobo, 2010 Nobel Peace Prize winner and professor of literature, who is serving a prison sentence of eleven years since 2008 for “inciting subversion of state power”. This so-called subversion was Liu’s participation in writing the Charter 08, which called for human rights, freedom of expression, an open election system and a more democratic government.

Ask Liao Yiwu, a writer and musician who was jailed from 1990-1994 for writing a poem (a poem, no less!) about the massacre at Tiananmen Square. Despite the government banning him from travel abroad, Liao managed to escape from China by crossing at the Vietnam border in 2011 and now lives in Germany. At the Leukerbad literary festival in Switzerland in 2013, I had the opportunity to see and hear Liao perform a most heart-wrenching and deeply-disturbing poem about his time in prison.

Ask Guo Quan, who was sentenced to 10 years for requesting open elections and criticized the government for their poor handling of the 2008 Szechuan earthquake.

The list goes on.

From the outside looking in, from what you read in the international business press, you get the impression that China is booming, that the new Chinese “middle class” is thriving—finally enjoying the fruits of their hard labor. Although China’s so-called growing middle class approximates something close to the entire US population it still doesn’t even represent a quarter of China’s own (surely the middle class should represent the nation’s broadest group of people). Most of this (what I would call) wealthy “managerial” class live in the big coastal cities, and yes there are many rags-to-riches stories, and yes, China does have more billionaires that the US—many of whom have made their money in the last 10-15 years, but believe me, Tom, the great majority of China still lives under the yoke of the Communist Party and their locally appointed delegates (these are the modern Chinese warlords—or robber barons). Just recently, the Financial Times stated that “Communist China has one of the world’s highest levels of income inequality, with the richest 1 per cent of households owning a third of the country’s wealth.” In 2014, the net income of rural households is still below $ 100.00/month [ten years ago it was below $ 50.00]. Over 80% of 1.38 billion people are migrant workers or working class folk, and less than 2 percent of them earn enough to pay income tax (Bloomberg).

Make no mistake, modern day China is still a fully-fledged authoritarian feudal state.

TB: They might even catch up with us Americans in percentage of the population in prison.

MV: Even officially, they’re getting close. Officially, 1.7 million compared to the US’s 2.2 million or so. Though who actually believes the Chinese government’s statistics? The worse figure is the number of executions. Death Penalty Worldwide estimates that there were over 2,400 executions in China in 2014, and apparently that number is not in decline. The Communist Party will not release official figures on this, stating that the number is a state secret. Compared that number to the next worst, Iran and Pakistan, who executed around 900 and 320 respectively, and you start to get the picture. Amnesty International says that in 2105, China carried out more executions than the rest of the world put together. Also, bear in mind that many of those executed are prisoners of conscience. There are still others who say that even these figures are underestimated—aside from the official prisons, there is a whole network of gulags, labor camps, psychiatric facilities, detention centers and jails within the Chinese government’s Laogai system (Laogai, meaning “Reform through Labor”).

I am sure you will have heard of the forced harvesting of organs from prisoners on death row. On June 22 of this year, legal activists and journalists, David Kilgour, Ethan Gutmann, and David Matas released a report called Bloody Harvest/The Slaughter – An Update. In this report, they estimated that there were up to 110,000 transplants conducted per year in China, as opposed to the 10,000 per year that the Chinese government claims. Gutmann calls this one of the greatest cover-ups in human history. He estimates that from 2000 to 2008 over 65,000 Falun Gong practitioners were imprisoned, then subsequently harvested for their organs. According to Gutmann, significant quantities of these organs are also being exported. It appears that the government and the local police and militia may well be in collaboration to imprison Falun Gong practitioners, Uyghur Muslim, Tibetan and Christian activists and harvest their organs, or export their plasticized bodies to scientific institutes or museums abroad, all for the profit of the Party.

TB: Horrific! I had heard tales when I lived there of the black-market blood trade. Thousands of villagers supplemented their meager incomes by selling blood. Isn’t there a Chinese novel about that subject and the subsequent spread of AIDS in the nineties?

MV: Yes. The one that comes to mind is Yan Lianke’s novel Dream of Ding Village. The novel’s main concern was the AIDS epidemic in rural China which people were getting due to the recycled needles in the black-market blood banks (Several times, early in the morning I myself witnessed “recyclers” sorting through pills and medical supplies in the containers behind the back of hospitals. These pills and needles are then repackaged and re-sold as if new on the black market. You can actually buy them on market stalls throughout the country if you know the secret password.) The Chinese government did their best to ban Yan’s book, but it was released faithfully in Hong Kong and Taiwan, and translated into English by Cindy Carter (Grove Press) only a few years ago. Which brings to mind the more recent abduction and strange disappearance of several bookstore owners in Hong Kong … It never ends, Tom.

One year while visiting the Canton (Guangzhou) Trade Fair, I stumbled across two Australians in a bar after hours. They proceeded to tell me about the explosive business they were doing in Chinese hair. They claimed they were exporting tons of containers of it, all over the world. The main use for the hair was in replacing yeast for industrial baking manufacturers—mostly those guys who make that bleached-white, pre-sliced, plastic-bagged stuff. Apparently when melted down and combined with other substances, the hair worked just as well as a leavening agent. Needless to say, I have never eaten that chewy, white pre-sliced bread since. That encounter with those businessmen is featured in the poem in Mao’s Mole, “The Five Cantos of Canton Fair.”

And yes, that painting of Mao, the “Great Helmsman” has loomed over Tiananmen Square for over forty years! His body preserved in a layer of paraffin, in an earthquake-proof crystal sarcophagus, remains the No. 1 tourist attraction in Beijing. He receives thousands of visitors every day, many of whom grace his casket with flowers they purchase from the dozens of vendors selling them on People’s Square. At the occasion of his 114th birthday on December 26, 2007, over 17,000 people visited his mausoleum. They came from all over China to see a dead man’s decomposing body—or is it just a poor wax copy? (There are theories that Mao’s body has long since crumbled to dust and the body has been replaced by a Madame Tussaud-style imitation.)

Either way, tell me Chairman Mao is no god, Tom.

TB: We stood in a Brobdingnagian line to see the dead Mao, and all we got was an orange jack-o’-lantern. But there was an old peasant in front of us who was trembling in religious ecstasy. Or maybe dehydration. An insane place, which you seem to understand as well as any dabizi I’ve met.

MV: China is a country of great extremes: extremes of landscape, of language, of history, of cultural evolution. China is eclectic, naïve, bold and brash, delicate and sensitive. Mao turned the working class against their warlords and created the “Cultural Revolution”, but really what happened is truly Orwellian. With the civil war won and the bourgeoisie cast out, the farmers and metal workers became the new warlords. The current-day Empire is just a rebooted version of the same that persisted hundreds of years prior. Here’s Liu Xiaobo’s take: “Beijing has served as the site for many ancient dynastic capitals—relics and ruins are everywhere—so it’s especially easy for people to think of an autocratic monarchy. In this place long ago emperors presided over ritual offerings to Heaven at the Temple of Earth and the Temple of Heaven, though for the purpose of ushering in the twenty-first century, to build another ‘Temple of the Chinese Century’ … just to satisfy the vanity of the potentates … even the taxi drivers saw it as a kind of monarchical, ritual demonstration of supreme imperial power.”

Nothing changed, just the symbolism.

So, to give you a very long answer, the reason I wrote Mao’s Mole, a collection of seemingly disparate persona poems about the last 100 years of China—the way I have come to understand it—was because to me it represents everything that has become of humanity. Mao’s Mole, more than anything else is an allegory of the birth of “modern” civilization, which, in my opinion, can be applied to virtually any empire; any empire trying to re-invent itself. From the outside, the symbolism, the metaphors, the mythology may look strikingly different, but from the inside, it is exactly the same. History repeats itself.

So, to give you a very long answer, the reason I wrote Mao’s Mole, a collection of seemingly disparate persona poems about the last 100 years of China—the way I have come to understand it—was because to me it represents everything that has become of humanity. Mao’s Mole, more than anything else is an allegory of the birth of “modern” civilization, which, in my opinion, can be applied to virtually any empire; any empire trying to re-invent itself. From the outside, the symbolism, the metaphors, the mythology may look strikingly different, but from the inside, it is exactly the same. History repeats itself.

I left China when my father-in-law was dying of cancer in Iceland. I had finally found an excuse to leave. The reality is though, that through his passing, and the months of mourning that followed—particularly with his beloved wife (she herself was starting to develop dementia)—I began finally to see what I had created in the Middle Kingdom with nothing more than contempt. Life should not be lived that way: on the edge of your seat, by the seat of your pants, as a stranger in a strange land. Our goal had been to, yes, build a successful, innovative, creative and exciting enterprise, but also to give something back, to help educate, to improve lives. The obstacles became insurmountable. We realized that China would never embrace us as one of its natives—even though for all intents and purposes I was born in its cradle. Imagine a world where someone is trying to undermine everything you stand for every minute of the day, where clandestine trench coats follow you into the public toilet, where you know your phone is bugged and your emails are being screened. Imagine a world where no matter how good your intention, you are cast out.

Mao’s Mole began as a kind of exorcism and evolved into an exposition of the fundamental mores, needs, desires and beliefs of a country, an empire, a civilization. A mirror of an everywhere that you recognize but don’t quite see clearly up close. On its pages, a multitude of voices appeared—each voice, Chinese or foreigner, exposing some intimate detail of his or her life and perception of their environment; each voice a fragment of a giant mirror. Therefore, Mao’s Mole: the hairy mole on the face of things; the furry mole in the earth—creator of vast tunnel networks; the mole standing behind you, taking meticulous notes with the purpose of turning you, taking you out or breaking you in: all reflections of the quintessential citizen in a unique yet strangely familiar environment. (Also, you may know this, but many Chinese believe that a mole strategically located on your face is a sign of good luck.) Mao’s Mole was a book that had to be written—and in many ways, it helped me find my way back into a deeper appreciation of the lyricism, of the profound resonance of language.

TB: To what extent has Chinese poetry, in particular its emphasis on visual presentation, caused your own work to vibrate on the page in the unique way it does?

MV: In the Chinese, of course, the visual language, the flow and flourish of the script is just as important as the words themselves. Chinese poetry—in its “finest” form, as written in calligraphic script—is both a work of visual and linguistic art. In that sense it is more multi-dimensional than poetry in the English language.

Chinese characters are logograms, of course—non-alphabetic—and many are derived and evolved from earlier pictograms. Legend has it that the Chinese script was invented by Canjie, historian to the Yellow Emperor (2650 BCE) and was inspired by flora and fauna, by landscapes and nature. (Previously the Chinese language had been documented with a rope-knot system, much like the recording devices of the Incas.) Over the centuries, these original characters—which were clearly depictions of nature—morphed, became more stylized, took on new or adapted symbolism. Of course, this is nowhere near the whole story, but the point is that Chinese characters, aside from their symbolic meanings also have a visual element that European languages lack.

Despite these differences, even in English, the visual presentation of a poem, how the lines break, how the blank spaces breathe between words, can not only enhance, but transform. I personally have sought inspirations for my visual presentation in not only Chinese, but also Japanese and Korean poetry. Of course, not all poems need a broad sweep on the page—each should stand as its own work of art, each its own rendering—visually or sonically. Surely every text is just as much defined by the placement of its words as its space on the page. (There’s that defining-space-thing again.)

TB: What is your opinion of Pound’s Sinophilia? Was it entirely, or just mostly, fraudulent?

MV: Pound’s Cathay “translations”, as is well known, were not really translations, but more interpretations inspired by the original texts. First off, Pound’s interpretations were based on Fenollosa’s notes of the poems—and Fenollosa’s notes were based on Japanese translations of the texts. Pound himself could not read or speak a single word of Chinese (or Japanese, for that matter).

MV: Pound’s Cathay “translations”, as is well known, were not really translations, but more interpretations inspired by the original texts. First off, Pound’s interpretations were based on Fenollosa’s notes of the poems—and Fenollosa’s notes were based on Japanese translations of the texts. Pound himself could not read or speak a single word of Chinese (or Japanese, for that matter).

To be fair though, on the cover of the original it does stipulate: For the Most Part from the Chinese of Rihaku, from the notes of the late Ernest Fenollosa and the Decipherings of the Professors Mori and Ariga. It is therefore quite obvious that these were not really translations. On the surface of it, Pound seems to have missed the mark altogether. On the other hand, as many critics have said, he created a whole new aesthetic of modernism through this seemingly ludicrous exercise. Fraudulent? Perhaps. Fascinating? Absolutely. Even though there were only fifteen poems in the book, it inspired all manner of imitations and was pioneering in its own fashion. Had he not referred to them as translations, he would likely have suffered far less vitriol.

TB: Any breathing of the word “China,” these days, conjures environmental nightmares. All your books, not just Mao’s Mole, traverse great swaths of murdered terrain. Are you, at some level, what is called “an environmentalist poet”?

MV: First off, I think I can say that I have been a first-hand witness to the absolute rampant destruction of the environment by industrial waste and pollution—several of my poems deal with specific cases of this too. For example, the poem, “Seepage” (which is in Mao’s Mole), concerns a discussion that I had in the Czech Republic in the nineties. I was working with a factory there. I recall a conversation with the then-General Manager, who informed me that although the shareholders were trying to sell the plant, there were grave issues with the groundwater. So many years of industrial sewage had taken its toll; and yet, the shareholders were selling the plant to Western buyers without even a hint of future implications. Sound familiar?

Then there were the years I spent living in Shanghai—where air pollution levels are now critical—or the many factories I visited during my time in China. Not a single one of them was without its environmental issues. We tried our very best to convince the suppliers we worked with to improve working conditions, to clean up their emissions and effluents, but there is only so much you can do. For many of them, the cost was prohibitive—and there were few, if any government incentives to change or support improvements in pollution control. Meanwhile, as they put it, thousands of workers were counting on the factory for their livelihood. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

During time off from work, I would travel to more remote regions of China: the far West, Tibet, Mongolia, swaths of Manchuria, and what I saw in some of those places would make your skin crawl. I haven’t even scratched that surface in my writing. I recall traveling in the province of Shanxi in the late nineties. Shanxi is a center of coal production and boasts—quite gleefully—over 2500 coal mines, including, believe it or not, one which now functions simultaneously as an amusement and theme park (only in China). I’m not sure you’ve been there Tom, but believe me, the coal gets in everywhere. When you return to hotel room at the end of the day, you wipe your nose and the Kleenex is pitch-black. I remember driving along the potholed roads, observing the multitudes of school children walking barefoot, their feet blackened by soot. One government official had the audacity to tell me that they didn’t need shoes since their feet were already coated by the coal.

Walking along the Shanghai Bund in 2014. Pollution has now reached its highest levels. Credit: Reuters / AFP

TB: Having been compelled to sit at banquets with such officials, I am not surprised by that. What an appalling thing not to be surprised by.

MV: Meanwhile, glaciers and icebergs are melting, sea levels are rising, the tap water in many of the world’s most populous places is contaminated, bee colonies are collapsing, wild fish stock is seriously depleted, whales are going deaf from all the ocean traffic—dare I go on? How could a writer living today not touch upon these subjects? And, above all else, how could capitalism’s exploitation of nature’s resources and the arising ecological problems not be attributed to the rise of “civilized globalism”. Governments around the world—despite fair and urgent warning from scientists, despite escalation in natural disasters or manmade disasters—are still turning blind eyes. These issues must be addressed—and so, I turn to the medium I have at hand to shout as loudly as I can.

TB: Does any of this lyrical yelling effect any real change?

MV: Auden famously said, “Poetry makes nothing happen.” Of course that delicate subject of politics or activism in poetry has been much debated. Seamus Heaney advised serious caution, fearing that it has a tendency to devolve into propaganda. That balance is so easily tipped—and yet, possibly that very risk makes the process all the more … invigorating. As David Orr has noted: “… a poet is always engaged in battle, though the opponents may be unclear . . .” For me, personally, it has less to do with effecting immediate change per se, but more about providing a varied perspective of the state of things—less so in swaying the reader of any specific opinion. Historically has not all Art reflected the sentiments and aspirations of the day—however naïve they may be in retrospect?

On the surface, few believe that change can occur through rhetoric or wordplay and yet, a critical mass appears to be as easily swayable today as they were during the rise of the Communist parties of China or the Soviet Union or the National Socialist Party of Germany—or even more recent brain-scrubbers like Sun Myung Moon and L. Ron Hubbard. Public figures and media addicts somehow manage to float on even the flimsiest of logic. In the end it appears that it is emotion that sways a populace. How else could millions follow the obvious maniacal rants of a rug-headed, ineloquent narcissist whose family rechristened themselves after a deceptive playing card?

Unfortunately, Tom, poetry—at least in the English-language world—has become an art form much like making origami swans or Morris dancing, well outside the mainstream. Unlikely that it can effect any significant change (in China, on the other hand, people still go to prison for it). There is now a deluge of digital distractions. Attention span is surely one of the major culprits: the visual ecstasies of film and the addictive qualities of the internet require far less effort.

It would be easy to throw in the poetic towel. And yet, there is a small but appreciative audience out there, even forgetting the poets and academics themselves. This may sound rather idealistic, but surely if even the lick of a phrase or word, the glimmer of an image, resonates somewhere else, that must be a positive force. … I sometimes wonder if people have become deaf to the music of language—which is very strange if you consider how language most likely arose.

Either way, I am compelled go on with this freewheeling medicine show.

I am no scientist, nor can I claim to have any particular foresight into issues that others have been pointing out for decades. What I do have, however, is first-hand experience at the level of industry—in China, but also India, Bangladesh, the former Soviet states; and of course, their counterparts in the West. No goods manufactured, distributed or consumed are ever sold at their true value. Surely this is “ecological corruption.” Are there still places in the world where nature is pristine, where snow doesn’t turn black in a matter of hours, where you can drink water straight from a stream without being worried that you’ve set off a chain of events in your blood stream that will eventually lead to you dying of cancer? Hard to say, but I am hopeful, so I would say yes. It is imperative, therefore, for me in my work to address the issues of rampant industrial globalization and its effects, but also to recognize the great beauty in a blade of grass or a rainforest or an ant or a cockroach—which, thanks to some kind of incredible resilience, still survive.

After leaving China, I moved to Iceland, which was where I found my calmest inner voice. Iceland—a place more pristine than any other I had lived before—still lives and breathes within its own nature. At any rate, to answer your question: Do I consider myself an environmentalist poet? You bet your arse, yes!

Thingvellir in southwestern Iceland, the seat of Europe’s first parliament in 920 AD and very close to where Vincenz lived in Iceland and wrote “Mao’s Mole”. Credit: Marc Vincenz

TB: Here’s a favorite of mine from Mao’s Mole, “Atomkraft 1967”—which, of course, was a crucial year in Mao’s purge of counterrevolutionary figures, and the year he acquired the know-how for the atomic bomb. (Nixon visited Mao in 1972, presumably to ascertain what his atomic aspirations were.):

Zhong Guo* means the middle country;

the middle way**, the path to liberation.

Coal thieves on scooters

dig from the middle of the earth,

separate the temporal from the permanent,

burn fires that melt iron ore

and draw curtains over the skies.

The old man wished for the atom bomb,

but Stalin wouldn’t give it to him.

In 1967, he got it.

He dredged fish from lifeless rivers,

fed souls with limp clothes

and hungry eyes.

As we were told, in our Village Cooperatives

and People’s Communes,

real miracles could happen.

In 1970, he launched satellites

straight into heaven,

to give us an eye

on the world.

I’ve been told you can’t split the atom

any way but down the middle.***

TB: * The Mandarin word for China, which also means the middle nation or kingdom.

**/***ironic, because “the middle way” is also the Noble Eightfold path of Buddhism which aspires to moderation, leading to complete “emptiness” that transcends “atomic” existence.

TB: You seem, lately, to be bringing these hugely far-flung worlds, traditions and idioms together into a composite poesy and mythos, planetary rather than regional. Is this a conscious project? I would think, if you set explicitly out to do such a Herculean labor, it might be daunting, to say the least. But, reading your books in succession, it feels more like a—to use the devalued term—organic process.

MV: The process is self-aware only in the sense that I search for the source of a common river, aided in part by myth and legend, but also by those linguistic entropies I touched upon earlier.

My literary mentor as an undergrad at Duke University was Reynolds Price. He was constantly telling me that I might run aground on the same shores that William Blake was beached—with my mystical language and magical approach to verse. Reynolds preached complete clarity, and was mostly lauded for it (although he is predominately known for his fiction). And yet, Reynolds, aside from being a poet, fiction writer, non-fiction writer and novelist, was also a Milton scholar. T. S. Eliot himself famously said that Milton’s “syntax is dictated by a demand for verbal music, instead of any demand of sense.” A little strange coming from the author of that oh-so-modernist The Waste Land, eh? I am certain that Reynolds was delighted with his own dichotomy.

The actual outpouring comes organically, as you say, however it can and may be induced by train journeys, earthquakes, mountain paths and or encounters of a circumspect kind. No, seriously, I would say it is a natural other-dimensional state of awareness, no more than slipping into or shedding of a second skin. It hovers there all the time: a parallel state of reality—a would-be-could-be-probably-will-be. There’s that foresight in the firelight again, that sense of reaching into the primordial fire: the realms of mythology and magick, the realm of “sacred” symbolism.

From time to time, there are themes or images that arise in those semi-conscious moments that drive the narrative along its axis mundi (or axiom). These may arise in the moment or come much later. It doesn’t really strike me as a Herculean labor, rather more of a natural wandering, almost as if I were walking though a familiar landscape: a forest, a cove, a plain, a valley (there you see that sense of filling in space along a stream of words). Ernst Halter rather aptly explained his own process as one of traversing a great body of water and somehow having a second sense as to where he might encounter the next atoll or islet. The journey itself then becomes the network or web that links these islets into a Oneness. It is a kind of working in reverse: knowing the goals, but not quite knowing their precise location. Only after the journey can the map be drawn and charted. (Interesting to note that my mother’s father was a surveyor and cartographer. I still have his fifty-year-old brass theodolite in the bottom of a trunk somewhere.)

Often, I will leave those preliminary verses to sleep for a while, sometimes even several years. At times, the story is still unfulfilled, other times it is the image or the sonic work that the language is trying to accomplish that remains incomplete. Either way, it rests. Alone. Perhaps in a drawer, perhaps under a pile of papers, perhaps floating somewhere in a lost suitcase or a shoe box (as a wanderer I am continually packing and unpacking). When rediscovered, it finally evolves—or in some cases, sadly, devolves.

One of the greatest pleasures is coming across this older work without any preconceptions and re-working the piece as if adding the final brushstrokes to a visual work of art. At times, the colors and textures are so much more obvious at this stage, and the final poem just slips right into place—as if it had intended to do that in the first place, but needed somehow to ripen. And, in those fortunate occasions, a certain spontaneity will arise whereby everything almost occurs simultaneously and you are even amazed yourself that the solution had not occurred earlier.

So, in a sense, the initial work is to gather the colors, the sounds, the impressions; to place them into a space, a jug, a jar. Only when the fermentation is just right can you pour out that language alive in possibility.

TB: Amanda Mitchell in the Yemassee Journal said that she found it “difficult not to regard Becoming the Sound of Bees with reverence, as it leaves one hushed and listening for humming over the hills.” She follows with: “This collection asks that we reexamine what we’ve placed upon our pedestals, what at any moment might crumble, what sort of legacy we will leave behind.” Tell us a little about how Becoming the Sound of Bees came about.

MV: In my mind’s eye I conceived an environment that slowly became populated with “oddments and things”: rocks, fossils, shrubs, birds, a flotsam-strewn beach, a mountain range, a bank of vacillating clouds, the microcosm of a tree trunk or a patch of earth. These served as a kind of backbone from which the rest of the work branched out. The visualization of the landscape created the voices, the moving imagery. The characters moved in and out of the permafrost, of the snowflakes and the clouds. I simply watched them breathe their own life into the work. As a result, the dramatis personae began to evolve. These incarnate beings (no matter their base element), lead the conversations and, as a result the ensuing poems and the book took form.

Plato said the world is divided into a world of being and a world of becoming. That Becoming was one of the inspirations for the book—and in many ways, set the initial stage. As the book came alive and began ordering itself the mythological world came into clearer focus. Much of the action takes place in or upon water, in rivers, oceans, along the seashore; in fact, the sea and her life-giving tides are a central metaphor in the book.

TB: In John Tranter’s Journal of Poetic Works, Robert Archambeau intimated that your work may just be “…the emergence of a new poetic …,” that each previous collection is somehow linked or mirrors the previous collection. Was that your intention?

MV: I am grateful to Bob for saying that. The books certainly do echo each other, following the longer path of those themes, images and sonics that were developed in those that came before. For the most part, while I am working on each collection (even if simultaneously), that particular body of work consumes my immediate attention. However, I do write books rather than individual poems—or rather, individual poems that are integral in the form of the book.

TB: In Becoming the Sound of Bees, I was particularly taken with the poem “Continuum.” In that poem you appear to momentarily step away the Ivan narrative and inhabit some kind of a hive mind. It is displayed horizontally in the book itself, clearly differentiating itself from most of the other poems. Unfortunately we can’t display it as it appears in form, but here it is:

We multiply best

in open bodies

with low mass indices

warm and flock

cluster and conjoin

in dances mimeographed

by mysterious natural

forces undeciphered

faithless phenomena

but orbed ringed

swerved or hooked

collectors congestors

of congenital immunity

diplomatic border-busters

eye upon unwavering eye

one as many as

many as one collectively

as right to civilize

diversity as right

to arithmetic mutation

towards adaptation towards

conceptualization towards

definition and tradition

solidifying in constituents

of a periodic table

as yet uncompleted.

They prisoners

of a singular atomic vibration

high mass index inclined

confounded to expansion

of the straight and narrow

contrive through surfaces

beyond the own layers

in the closed exoskeletons

of their own devising

matter being matter being

eye to eye too

without critical observation

nor mysterious compunction

but for degenerative

deconstruction that rubble

may build rubble

may build rubble again

each succession wired

into the value-chain

of being and non-being

that a creator may

draw strings and each and every

last one may last

beyond the great oblivion

at the end of all things.

TB: Can you provide me / us with some kind of road map? How does it fit into the book and who are these souls that are talking to us?

MV: I am going to return to Ernst Halter’s analogy here, and say that there are several atolls or islets in the book, the first being the opening epigraph from Louis Pasteur, “Life is the germ.”

TB: The first poem in Becoming the Sound of Bees, which I believe serves as a kind of prologue, in the poem “Transmigration.” Do I sense a whiff of foreshadowing in the poem? It is certainly a striking introduction to the world of this book. Here are the last four stanzas:

And when we emerge, some of us less

than half the men we once knew,

in one blinding flash, as dog greets master,

that curious light comes running. And then,

hovering for a split second, panting

over a torn scrap of cloth,

a flapping shoe sole, continues,

right out the other side.

MV: The book is undeniably about transformation, “becoming,” moving into a new form or state—much in line with the creatures we evolved from. And, yes, certainly a foreshadowing.

TB: Of course, I have a special relationship with another of your recent books, This Wasted Land and Its Chymical Illuminations. Please talk about that.

MV: As you well know, Tom, This Wasted Land, and Its Chymical Illuminations is very much a tip of the hat to Eliot and Pound. And, of course, the entire book is a finely tuned farce. The incipient idea, and I wouldn’t really call it that, as it came to me involuntarily, was to update Eliot’s work into a modern idiom. Of course, that is not what occurred at all. Although structurally similar to Eliot’s poem, This Wasted Land has an entirely different narrative. And yet, it does follow a similar arc—not thematically, but sonically.

As the poem was getting closer to completion, you were developing the annotations. The sense we both had was this: how many lines of a single poem could refer to something else out of literature or history. And thus, somehow to show how random the referential process was / is, the wild and broad references. A line of poetry may be interpreted a multitude of ways, and yet, within a context it becomes something specific. I suppose, on some level, our goal was to prove how random that process is. Of course, everything is influenced by what came before it; of course, each piece of literature is interwoven with what came before—and yet, this “strain,” these “constraints” of academia—of willing something to be a part of something else—well, we just couldn’t resist. So, there you have it. A farce within a farce, nailed to the gossamer roots of academic empiricism. As to the annotations, in the words of the mysterious Sigfried Tolliot who wrote the afterword (the name popped into my head as I was working on the poem): “Displaying what can only be described as flippant disregard for intellectual rigor, Bradley has sunk alongside T. S. Eliot into ‘remarkable expositions of bogus scholarship.’”

The goal, of course, was not necessarily to punch holes in modernism. Seriously, though, Tom, what is modernism anyway? Did not the Romans consider themselves modernists compared to the Greeks?

TB: Yeah, but without the uppity whippersnappery of Pound and pals. What else are you working on at the moment?

MV: I’ve been working on three different poetry collections: tentative titles are Unspeakable Desires, which is currently seeking a publisher, Something Stereophonic Unsettles the Breeze, which is nearing completion and 70 % Off, which is a poetic study of capitalism and consumerism.

TB: Three collections simultaneously? How does that work? And, I’m sure you have other translation projects in the works too, right?

MV: I have a fairly low boredom threshold, so I need to have several projects ongoing at the same time; and for the most part I’m always working on multiple books. I’ll write a poem, for example, that seems most appropriate for one of the books I’m herding together; then that poem will slip into that book; then I’ll write another which seems more appropriate for the second book. Of course, at times the individual poems may find themselves migrating elsewhere, but in principle that is how I work on the books simultaneously. And yes, I am also working on several translation projects at the moment—they also give me a break from the rigors of the blank page.

TB: Can you tell us what Unspeakable Desires is about?

MV: A little too early to pull the cat out of the bag entirely; the book is very much concerned with language, meaning, the nature of reality and an attempt to decipher it. There are many whisperings in this book. These “voices” and their own machinations and biases influence the central figure, Uncle Fernando, on his travails. His main companion and counterpart, Sibyl, is a muse or an oracle—or at least, he believes she is. The Muses, as you know, in the ancient Greek sense, were considered as the divine sources of knowledge, literature and myth: divine inspiration. And, as you probably also know, the oracles, the sibyls, spoke in mysterious riddles in the glossolalia of the gods. Here too, Fernando’s great dilemmas arise.

I perceive the narrative as a weaving in and out of the conscious, subconscious and somewhere else in-between; perhaps more like the way we think; or, more specifically, the resonance of a palette of languages, images and sensations that we all retain somewhere in our memory-bank which resurface / emerge as we encounter the familiar or the almost-new: a non-linear phenomenon (that may include a multitude of voices, sounds or sensations) that shapes our responses and colors our views in the now.

TB: Sounds fascinating. We would love to read one of these new poems from Unspeakable Desires. How about “Uncle Fernando’s Advice on Flyaway Hair”?

MV: Okay, here it is:

Have you taken note

of the drift

of your own South Sea Islands?

Have you considered how long

they’ve held their heads

above the bruised coral reefs?

and how long will

the manta ray

cast winged shadows?

and do not forget those lonely fishermen

with their whitebait and tin traps

opening the can over and over until

they have only scraps and scrapings, ink and

paper on calluses, or depth charges

that run wild where continental plates collide.

Do the ghosts of their catches circle your boats

in shoals as the gulls circling the city root deep

in the landfill of another bygone era?

Take note.

Observe everything.

One bird at a time.

TB: Fabulous, Marc. I look forward to reading all these new poems in the book when it comes out. Thanks for this interview.

About the interviewer:

Tom Bradley’s latest book is Energeticum/Phantasticum, coming early this winter from MadHat Press. He has published twenty-five volumes of prose and poetry with houses in the USA, England, Canada and Japan. Further curiosity can be satisfied at tombradley.org.

Recent Comments