My Life in the Land of the Eternal Spring:

The Coffee Plantation

By Mark D. Walker

Contributor

Though I had lived and worked in Guatemala for seven years, it was a brief encounter with my young daughter, Michelle, on the San Francisco Miramar coffee plantation, perched on the side of the Volcano Atitlan that would determine my direction in life. It was a few days before Christmas, and I was strolling through the “Big House” when I came upon her in the living room. She stood, her feet planted on the orange tile floor, hugging her new Airedale puppy, Tiky, and gazing with wonder at the Christmas tree twinkling with colored lights and filled with handmade decorations. Below the tree, a number of brightly wrapped packages sat in contrast to the stark white walls. On the wall were a number of photographs of my wife’s family members.

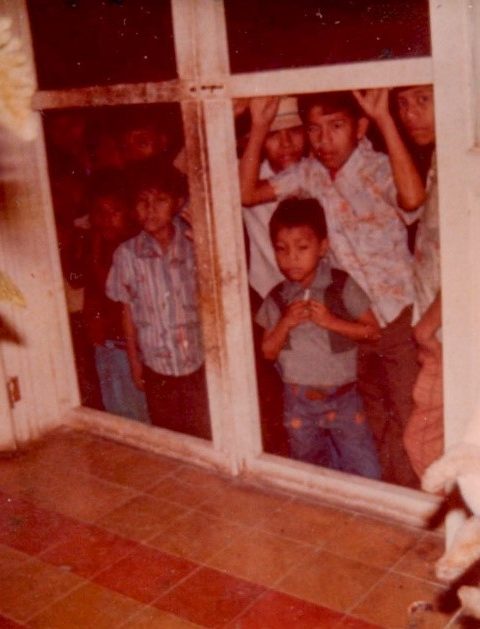

It was a perfect holiday moment until I noticed a dozen small children directly behind her pushed up against the screen door which opened onto the patio beyond. A soft evening afterglow highlighted the children, and I couldn’t distinguish their faces behind the screen. They stood, dressed in simple cotton shirts, jeans, and flip-flops, silently peering into the room. These were the workers’ children, who lived in little block homes below the Big House. The children were all so cute, so inquisitive, so innocent. None of them dared to open the door and come inside to join Michelle or touch the presents; they were relegated to peering in from the outside.

This scene would be branded into my memory as it represented the vast difference between the options open to these children in comparison to my daughter. Because I had married Ligia, the daughter of the “finca” (plantation) owner, Michelle was part of the family. Seeing the workers’ children reminded me what it felt like to be on the “outside” looking in. I’d never be totally accepted by Ligia’s grandfather and key family members, nor would I be invited to do anything but occasionally visit the plantation during holidays, whereas generations of her family had lived on and developed this coffee plantation over the years.

With mixed feelings of sadness, despair, and guilt, I kissed Michelle on the forehead, petted Tiky, and walked through the room and into a long hallway which led to a patio on the other side of the house. As I entered the porch, I found my wife relaxing in a wicker lounge chair gazing at the iconic green volcano, a slow mist covering its peak. I sat with her, asked one of the kitchen girls to bring a glass with ice, and settled in with a few shots of Johnnie Walker, Black Label Scotch Whiskey.

I told Ligia about the children peering into the room at the Christmas tree and Michelle with her puppy and she reminded me, “Well, all the worker’s children were up here yesterday afternoon for the traditional Christmas celebration which included piñatas filled with multi-colored hard candies. They all drank water with cinnamon or a soft drink and were given a small bag of plastic toys. Some of the local musicians played the marimba. They had a great time.”

Yes, I thought, but what chances do they have of ever getting beyond the coffee plantation and making a real living on their own? As a former Peace Corps Volunteer, my focus always started with the condition of the bottom rung of society—in this case the finca workers. In the past, at many coffee plantations, the workers would make a pittance and they’d be paid with finca currency which could only be used at the finca’s own “general store”. So, what they could purchase was limited to what the store deemed “necessary” based on the finca owner’s price system. The few plantations with schools only went to the elementary level, and their teachers often didn’t show up for work. If they were lucky, some children would make it to sixth grade. Only a few ever made it to a public high school due to a lack of transportation or horrible road conditions. San Francisco Miramar did have a basic health clinic, but many coffee plantations didn’t. The workers had access to clean water though some had to go to the river to bathe.

This contrasted with our daughter, Michelle, who attended a relatively expensive private school called La Asuncion. She was picked up and let off by a school bus owned by a Spanish order of nuns. Michelle wore a nice, crisp new uniform and always brought home homework.

I realized that I’d always be looking from the outside in, whether on the coffee plantation or working in the highlands of Guatemala. I looked over at Ligia and said, “I’m going to contact my friends at CARE International and my Canadian missionary friend, Alan, and find out who needs help doing some good grassroots development work.”

Ligia’s response was immediate, “Can you make a living at that? Your pay at the Peace Corps barely paid for food!”

“Yes,” I responded, “it will take years to gain the necessary experience and track record in order to work for an international relief and development group, but this is what I want to do.”

“Well,” Ligia responded, “you’ve worked in some of the most isolated parts of the country where none of my friends or family have ever visited and have your Masters from the University of Texas, so maybe it’s time to make a living at what you love the most—helping the kids who need a break.”

“For sure. We might as well get some mileage out of those two years we spent in Austin so I could get a degree,” I observed. “But I want our children to at least be aware of how lucky they are and to help out kids who aren’t as fortunate.”

Ligia’s response was simple, but direct, “It’s up to us to teach them to respect others based on how we treat them, in our home and community.”

As the sun ducked below the ocean to the west, the volcano loomed before us, green, lush, and imposing. The mist had lifted and the fire flies began flickering around the many colorful flowers and plants in the finca garden and the worker’s children began to walk down to their little homes. One mother called out, “Miguilito, why are you still up there? It’s time for the “patrones” (Finca owners) to have dinner.”

I took Ligia’s hand and squeezed it, “We’re so lucky that Mariano (her grandfather) and “Coco” (her uncle) have always invited us to relax here at the Finca. I’ve learned so much about life in Guatemala—the good and sad parts.”

As I gazed up the side of the volcano, and took in the sweet aroma of the coffee blooms, I realized that the finca would not be the site of my life’s work. My calling would be to join those of a like mind, working to assure that children of the humblest families would receive a decent education and aspire to a career of their choice and reach their true potential as God’s children.

About the author:

Mark D. Walker is the author of Different Latitudes: My Life in the Peace Corpsand Beyond. “My Life in the Land of the Eternal Spring” will be published in the fall “Crossing Class Anthology” published by Wising up Press. He is an active member of the Arizona Authors Association, the Society of Southwestern Authors, the Phoenix Writers Club, and the Phoenix Writers Network.

Recent Comments