Of Brooms and Ennui on the Île Saint-Louis

by L. John Harris

(Excerpted from “Café French: A Flâneur’s Guide to the Language, Lore and Food of the Paris Café.” Text and illustrations by L. John Harris. Forthcoming Fall, 2019 from el Leon Literary Arts.)

There is nothing so insupportable to man as to be in entire repose, without passion, occupation, amusement, or application. Then it is that he feels his own nothingness, isolation, insignificance, dependent nature, powerlessness, emptiness. Immediately there issue from his soul ennui, sadness, chagrin, vexation, despair.

– Blaise Pascal

Île Saint-Louis, one of two small islands floating in the middle of the river Seine and hyped in travel literature as “a peaceful oasis of calm” in the heart of busy Paris, is anything but. A tourist Mecca, bien sûr, filled with snazzy shops and restaurants and home to the legendary Berthillon ice cream. The scene is more Coney Island fun park than Parisian island oasis.

I’m taking notes in my journal today in the island’s trendiest café, Café Saint-Régis on rue Jean du Bellay, just across the Pont Saint-Louis bridge connecting Paris’ other natural island, Île de la Cité, where Notre Dame resides in all its gloomy Gothic glamour. The Café Saint-Régis is what I would call faux belle, refurbished to evoke the gaudy Art Deco grandeur of Belle Époque Paris, with gaudy prices to match. Like the island itself, the café feels cloying.

Living in a Parisian broom closet

Whatever joie de vivre Parisian cafés evoke, I’m not buying it at the Saint-Régis. Yes, cafés have their dark, existential side and revolutions and assassinations have been plotted, even launched in Parisian cafés. Suicides too. But my mood is more ennui – that nuanced French word for boredom shaded by melancholy or despair – than actual depression, suicidal or otherwise. How could anyone be that depressed on assignment in Paris with an address on Île Saint-Louis?

But the apartment I’m staying in is much smaller than the rental agency photos indicated. I vegetate (call it work if you like) in the island’s cafés, upscale and down, to escape domestic claustrophobia, something apartment-dwelling Parisians – and there are virtually no other kind – have been doing for centuries.

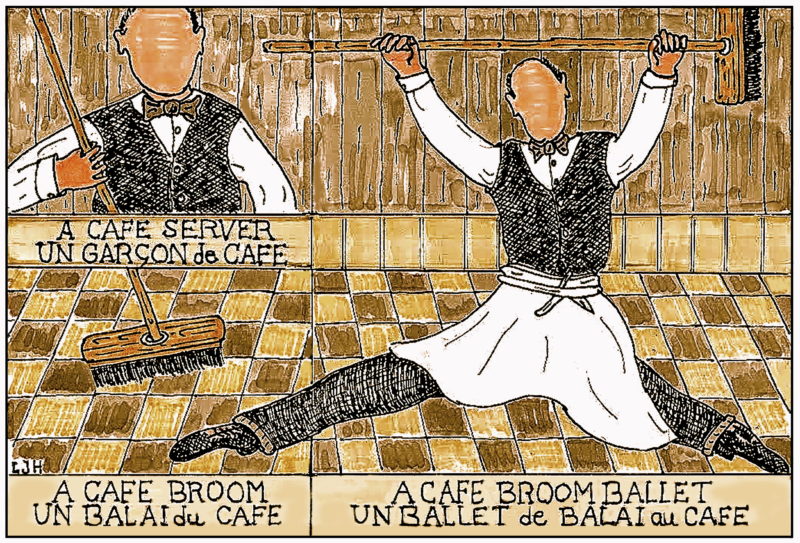

The only hint of joie today at the Saint-Régis is triggered by a garçon waltzing (literally) around the café with his broom—a Parisian push broom, a smaller version of the type of broom we use in the U.S. for exterior clean-ups. I could write a whole treatise on France’s bizarre broom methodology: In short, Parisians push, they don’t sweep.

A broom ballet on rue Jean du Bellay

Googling broom history and its etymology in both French and English, I come across – par hasard (by chance) – the Anglo-French homophones le ballet (the dance) and le balai (broom), identically pronounced: bal-ai. Ah ha! My server, dressed in formal café black and white, is executing un ballet de balai – a broom ballet. Ennui morphs into bonheur (happiness).

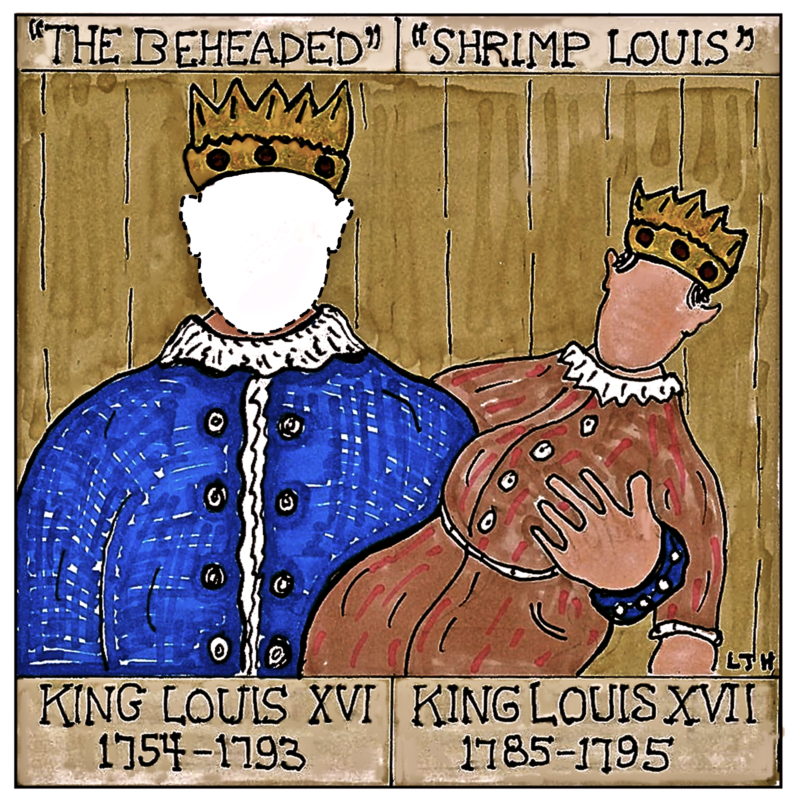

Back at the apartment, though, my mood darkens. Inexplicably, the sight of a broom leaning against the kitchen wall triggers more gloom. Maybe it’s a case of generic island fever; or the palpable weight of French history that floats in the bilious grey skies over the island like a monstrous gold crown dripping with jewels.

A whole lotta Louis goin’ on

Everywhere you stroll on Île Saint-Louis there are references to King Louis IX, France’s beloved Saint Louis and the island’s namesake. Bridges, streets, hotels, churches and cafés carry the name or variants. Even the word régis in Café Saint-Régis, means “of the king” in Latin. My modest corner café/brasserie where I go for my morning petit déjeuner is named Le Louis IX. It was Louis XIII in the 17th century, dubbed “the Just,” who developed the island’s urban plan – it had been a cow pasture. And it was he who named the island in honor of Saint Louis.

À propos of royal sobriquets, several of the eighteen French King Louis have earned less than flattering nicknames. In the 9th century there was “the Stammerer” (Louis II), in the 10th “the Lazy” (Louis V) and in the 12th “the Fat” (Louis VI). You could say that the French have had a love/hate relationship with their mostly House of Bourbon Louis. Honestly, I’m surprised there was never a “Shrimp Louis.” The likely candidate would be King Louis XVII, son of guillotined King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. Never attaining the throne after the revolution, the Dauphin died in prison at age ten. He didn’t live long enough to earn a snappy moniker. Now he has one, no charge.

Speaking of salads

If I thought my one-bedroom apartment was small, I was corrected at a dinner in the chambre de bonne (maid’s quarters) of the Paris guidebook author Annabel Simms, an English expat. Her book An Hour From Paris is a perennial seller in Paris and is designed to take tourists out of crowded Paris for memorable day trips.

The fifth-floor studio walk-up on the island’s main drag, rue Saint-Louis-en-l’Île (of course), is equipped with a tiny wall-mounted kitchenette: two burners with fridge and sink tucked under the counter. “And,” Simms boasts, “no microwave!”

Petite with short, dirty-blonde hair, Simms has produced a new cookbook geared to simple French apartment cooking. She serves me her version of Elizabeth David’s Salade Parisienne from French Provincial Cooking, composed of fresh vegetables, hard-boiled egg and slices of room-temperature roast beef (which she purchased cooked from a local shop) all dressed with a vibrant (leaning to the acidic) vinaigrette. Simply delicious and perfect for the warm summer night.

Over coffee our conversation drifts towards my host’s mixed reviews of her island oasis lifestyle. Simms has been living frugally and productively on the pricey Île Saint-Louis for more than twenty years and avoids expensive touristy spots like Café Saint-Régis. “I love their baby Spanish sardines served in the tin with the lid rolled up,” she confesses, “but I’d rather go to the cheaper Café Le Lutèce next door with its terrace facing north towards the Seine and the quieter right bank.”

The next day, back for a farewell crème at Café Saint-Régis before returning (at last) to the States, I ponder Simms’ somewhat cloistered life on Île Saint-Louis. It’s ironic that over the course of her decades on the island, she has built her career as a writer in Paris, a city she adores, based on a book that encourages tourists to get out of Paris. After only three weeks sequestered on the island, I’m ready to get out too.

About the author:

L. John Harris is a writer, artist, filmmaker and guitar collector living in Berkeley, California and Paris, France. He was one of the founding members of the Cheese Board Collective in Berkeley and is the author of The Book of Garlic (1974) and Foodoodles: From the Museum of Culinary History (2010). Harris presides over the Harris Guitar Foundation at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. His next book will be a history of Berkeley’s “gourmet ghetto,” to be published in 2020 by Heyday Books.

L. John Harris is a writer, artist, filmmaker and guitar collector living in Berkeley, California and Paris, France. He was one of the founding members of the Cheese Board Collective in Berkeley and is the author of The Book of Garlic (1974) and Foodoodles: From the Museum of Culinary History (2010). Harris presides over the Harris Guitar Foundation at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. His next book will be a history of Berkeley’s “gourmet ghetto,” to be published in 2020 by Heyday Books.

Recent Comments