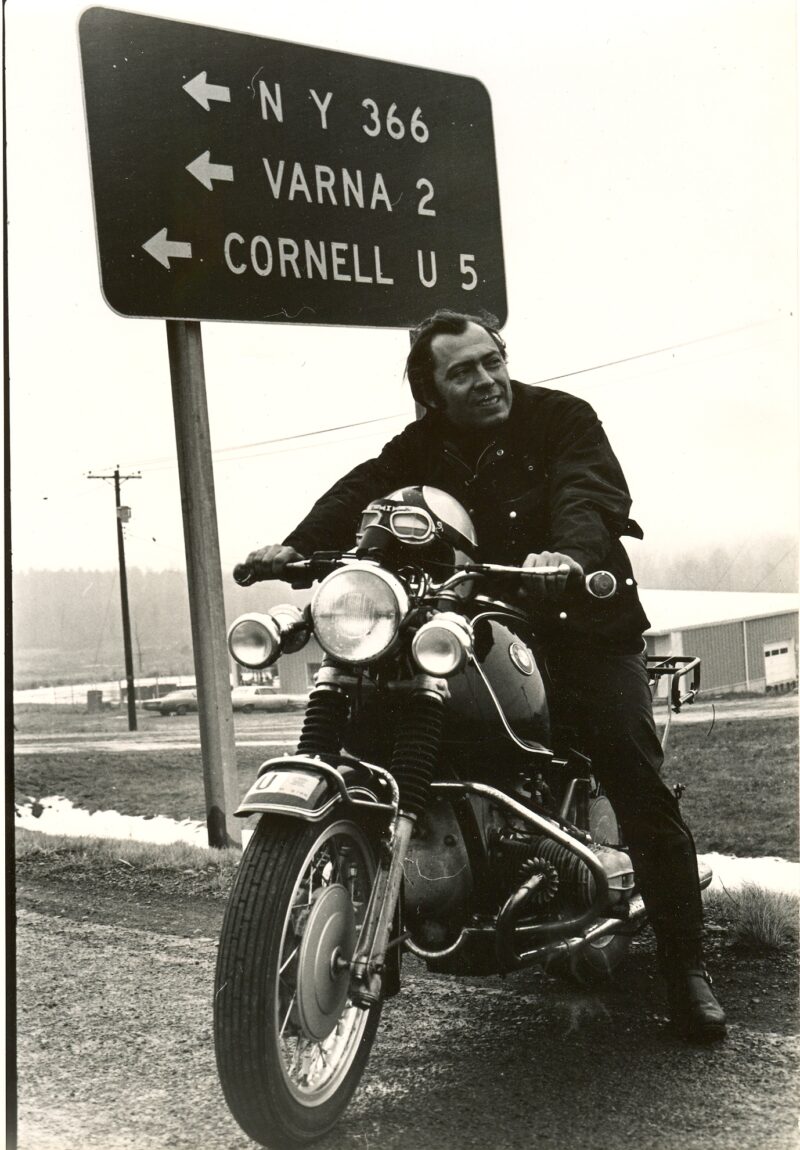

Steve Poleskie astride his BMW R69US, one of his motorcycles that never threw him down. Photographer unknown.

Taking Another Fall

by Stephen Poleskie

Columnist

At the end of my previous column I had implied that I might write about some of my other falls in the next issue. At the time I did not know that this was going to be Ragazine’s final issue. I thought to write an appropriate “goodbye” piece, but I had made an offer to write about one of my motorcycle falls and the horrendous treatment that I received at an emergency room in a New York City hospital. As I am now sitting at my desk in sheer agony from the treatment I have or have not received since my July 15th fall here in the small town of Ithaca I will write briefly, the pain in my back precludes a long article, about my visit to the emergency ward in one of the finest hospitals in Manhattan.

The accident occurred on the elevated section of the upper West Side Highway. It was night and I was riding my Honda 450 along with a pick-up group of bikers who met on West Fourth Street, and took off as a pack when the enough riders had appeared.

I was riding along contentedly in the middle of the pack on a nice summer evening. I must have hit a rut, or slid on an oil spill, when I leaned my machine over to pass a car. The next thing I knew was that my Honda was out from under me and sliding down the road, making sparks on the pavement as it went.

I landed on the road on my right arm and felt a definite crack. I ended up lying in the middle of two lanes as traffic whizzed by on both sides of me. I heard horns honking as the passing cars barely missed my body. Unfortunately, I had a full beard and was wearing a black helmet, a black leather jacket and black jeans so was almost invisible. I didn’t know then that my collar bone was broken, but I did know that the pain prevented me from getting up and moving to the highway wall, where I could stand up in safety.

I lay there waving my good arm above me for I don’t know how long. And then, as if by a miracle, some of the riders from the group appeared, which was amazing as we weren’t friends and didn’t actually know one another. They had gotten off at the next exit and doubled back. They held up traffic and helped me to the wall. In a short time an ambulance arrived, which someone from the group had called. This was not an insignificant courtesy at the time, as it was long before mobile phones were invented,and someone would have had to stop, find a payphone, drop a dime and call.

So I am here in the emergency ward of an uptown hospital, waiting with at least 100 other people for someone to see me. After the ambulance had dropped me off I stood in line for about 45 minutes, my shoulder in excruciating pain until my turn came to check in. The ambulance attendants had provided little care for me other than transport.

The woman at the desk asked me for some identification. Instinctively, I reached into my back pocket for my wallet, which was not there. Had it fallen from my pocket when I went down or been taken by one of the ambulance workers who had picked me up? Anyway, I was given a number, listed as a charity case, and told to go and sit down, in the big room, if I could find a seat.

I eventually found a place and sat down next to an elderly gentleman. I asked him if this ward was always so busy. His answer was that it was “just an ordinary Friday night in Harlem. . . .” I began to notice that many of the potential patients were being wheeled in on gurneys, while escorted by police officers.

My number finally was called. It was well after 10:00 p.m. and I had crashed around 7:00. I got up and was standing by the door to the emergency ward. I would be next. Just then a woman on a gurney was hurriedly pushed past me and in through the door.

“Hey!” I shouted to the attendant monitoring the door. “I’m next. How come she gets to go in ahead of me?”

“Because she has an emergency. . . .”

“But I have an emergency too, what’s her emergency?”

“Her boyfriend broke a beer bottle up her snatch and she’s bleeding,” was the attendant’s curt reply.

I had to agree that her emergency was more urgent than mine.

A doctor finally saw me. I was X-rayed and it was agreed that I had a broken collar bone. But a broken collar bone cannot be set, or so I was told. My arm was merely put in a cloth sling and I was informed that I could go home.

But how to get home? I wondered as I walked out into the sultry night air. I had no wallet, no money, no friends with me. I had thought for sure that I would be spending the night in the hospital and could work all this out in the morning. My abrupt departure had unnerved me. I had to make some kind of a plan.

It was now a little after midnight. The popular artist’s bar Max’s Kansas City stayed open until 2:00. I was well known there and had a tab. I would hail a taxi and convince the driver to drive me to Max’s, and wait out front while I went in to borrow money from the cashier to pay what would be a rather large fare.

This was easier said than done. Any cab that I did get to stop, for a bedraggled, bearded man with his arm in a sling, quickly took off when I leaned in the window and explained my scheme. And I was really beginning to feel my pain. The medications I had been given in the emergency ward were beginning to wear off.

I must have fainted for I woke up to find myself lying on the sidewalk; being kicked by two of New York’s finest. “Get up ya fuckin’ hippie, ya can’t sleep here.” They asked me for my ID, which I of course did not have.

They were going to take me in, which at the moment didn’t seem like too bad an idea as at least I would have a place to sleep. They changed their tune when they seemed to sense my enthusiasm for their scheme.

“Well you can’t sleep here on the sidewalk.”

“Could you at least drive me to someplace where I can get a cab? I can’t get one here.”

“We’re not allowed to ride civilians in a police car.” With that said the two officers picked me up and hitched me by my jacket to a nearby fence pole. Then they drove off.

I was hanging there half-awake waving my free arm at passing taxis, when one pulled over and stopped.

“Hey you! Why you hanging there?”

The driver was actually interested enough in my story to get out and help me off the fence pole. He agreed to take me downtown to Max’s.

On the way down we began a conversation. The driver was an aspiring writer who knew of the bar, although he had never actually been there. He did live down town and was happy to be going back after having reluctantly taken a fare up to Harlem. He was very interested in my tale of the past five hours, and asked if he could write it down as a short story. He was supposed to let me know if he ever published it, but I never heard from him again.

We pulled up in front of Max’s Kansas City, the fire hydrant out front having saved a space for the cab to wait. The bar was still all lit up and booming. The cabbie held the door as I struggled out of the backseat and went inside.

The cashier on duty was a young lady that I knew well. She was surprised to see me arriving so late, all disheveled and with my arm in a sling. I quickly explained my problem and how I had gotten into the situation I was in. She didn’t need to ask Mickey, the owner who was still there, but merely took the amount I had asked for out of the cash drawer and put it on my tab.

I went outside and paid the fare and gave the cabbie a huge tip. He volunteered to drive me to my loft at no charge as he was now off duty and on his way home. I thanked him and declined, I was going back into Max’s to talk to some friends and have a few drinks to kill my pain before it closed. I could walk to my loft, which was only three blocks away, and the night had become cooler. The air would do me some good.

About the author:

Stephen Poleskie’s writing has appeared in journals in Australia, the Czech Republic, Germany, India, Italy, Mexico, the Philippines, and  the UK, as well as in the USA, and in three anthologies, including The Book of Love, (W.W. Norton) and been twice nominated for a Pushcart Prize. He has published five novels and two story collections. Poleskie has taught at The School of Visual Arts, NYC, the University of California/Berkeley, and Cornell University, where he is a professor emeritus, and been a resident at the American Academy in Rome. He lives in Ithaca, NY, with his wife novelist Jeanne Mackin.

the UK, as well as in the USA, and in three anthologies, including The Book of Love, (W.W. Norton) and been twice nominated for a Pushcart Prize. He has published five novels and two story collections. Poleskie has taught at The School of Visual Arts, NYC, the University of California/Berkeley, and Cornell University, where he is a professor emeritus, and been a resident at the American Academy in Rome. He lives in Ithaca, NY, with his wife novelist Jeanne Mackin.

Website: www.StephenPoleskie.com

Recent Comments