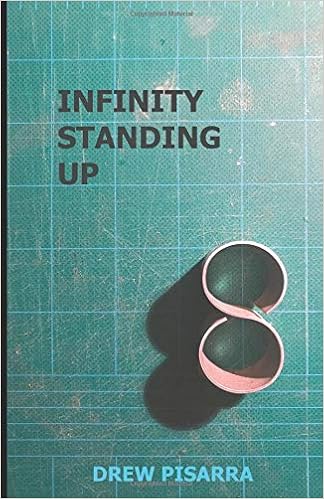

INFINITY STANDING UP

INFINITY STANDING UP

Capturing Fire Press, Washington, DC

ISBN: 978-1-7328759-1-3,

58 pages, $10.00

Review by Clarinda Harriss

It was a lucky day for me a review copy of Drew Pisarra’s stunning sonnet collection INFINITY STANDING UP arrived at my office. In two weeks I would be giving a sonnet workshop at Baltimore’s Enoch Pratt Library, and nobody could illustrate better than this contemporary sonneteer how to make manifold uses of the sonnet form and make the form the poet’s own. Playing with and against the sonnet’s inevitable clichés — the theme of love, numbers instead of titles — this collection thrills and delights. Imagine, if you will, a sonnet about a devouring a lover whole, ending with “Slurp!” Imagine a sonnet numbered “Pi.” Or “Gazillion.”

These unabashedly erotic and homoreotic poems range from buoyantly raunchy to deeply serious. With much “vision and revision” I chose two for my workshop: Sonnet $18.99 and Sonnet Infinity. (Sonnet Pi may make it into the handouts as well.)

S0NNET $18.99

You wouldn’t even let me treat you to tacos

because you equated me buying you dinner

with dating and so we watched YouTube videos

before sex then chatted like two shy beginners

post-boink, our eyes cast downwards or staring out

into the dark, unseeing. You spoke of the Mexican

novel for some reason. I wanted to talk about

feelings, briefly albeit. Then we fucked again.

All that ended with the following text last night:

“My boyfriend arrives tomorrow from Caracas.

Are you free now?” It took me six hours to reply:

“Love deeply, not widely, in both Americas.”

I wanted to blame you for making me feel cheap

but I knew you weren’t single. So who’s the creep?

Oh, you could walk into a crowded theatre and yell “18” and half the audience might well start chanting “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”(Shakespeare’s most famous sonnet was #18). But $18.99 means something thematic here. The price of a marked-down book. The cheapest thing on the dinner menu. A sum that wouldn’t pay for a hand-job. Cheap. Note too to the approximate rhymes (e.g. (tacos/videos) and minor accent rhymes (Mexican/again, Caracas/Americas). Thus the self-denigrating end with its resounding one-syllable full rhyme packs a hard punch.

SONNET INFINITY

On the subway this morning, I spotted your hair

on some other man’s head: unexpectedly unwashed.

It gave pause. So weird. How’d it get there? And who cares?

I had to look away and fast but then I caught

your eyes staring at me from an infant nearby.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not so deranged as to say

that baby’s baby browns were your two peerless eyes

transplanted. It’s just, throughout my surreal day,

I saw your legs, your arms, your neck reattached to

various torsos while your lips, your nose, your ears

landed magically on face after face. Who’s

to say what lies hidden inside some stranger’s jeans?

You are so on my mind even when you’re not here

that wherever I go, parts of you reappear.

Stifle, please, any complaints about the lack of a Shakespearean (or really, any) rhyme scheme. Pooh. My favorite among all the sonnets I’ve ever written happens not to rhyme at all. There are echoes throughout (say/day), cares/ears/here). And at the end, as in the most traditional of Shakespearean sonnets, a fully rhyming couplet. As for the theme of infinity, we all have experienced the seemingly ceaseless parting-out of a lost beloved’s features. But the “unwashed” hair — on someone else, yet — this detail is unique yet inclusive. We can smell that hair.

If I have dwelled heavily on P’s craft, I did so because the craft is great among the collection’s pleasures. At the same time, I recommend INFINITY STANDING UP highly to readers who even don’t like poetry all that much — but have been in love: “So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.”

An interview with the poet:

Clarinda Harriss: Why the sonnet? Is it its formal demands, its brevity, its history, or what?

Drew Pisarra: Clearly, you pen sonnets too, because of course it’s all those things. The formal demands kept me focused, the brevity ensured my train of thought never got too unwieldy during the writing process while the history of the form made me feel as though I were part of a time-tested tradition. There was a strange comfort in that.

CH: What IS a sonnet — its defining aspects? Gotta be more than just have 14 lines and a rhyme scheme.

DP: Mare Davis, who wrote the clever foreword for Infinity Standing Up, compares the sonnet to a dog crate, which I think succinctly captures the form’s essence: It’s a cage to which a certain breed of poet will return time and again. Some days, it serves as a holding pen to contain one’s frustrations; some nights, it’s a performance space for linguistic go-go dances. There may be an undercurrent of masochism in the sonnet, too, but at least the cage door stays open.

CH: Your sonnets cover a very wide range of feeling, from hilarity to grief. Was there something about the sonnet form, in its antiquity and its common association with love poetry, that spoke to you as, perhaps, a sort of irony?

DP: As absurd as this may sound, I think I saw the sonnet as the poetic equivalent of a peacock’s tail. I was hoping to captivate my muse with a bit of written splendor. “Look at me, I love you, now love me!” When that wasn’t proving effective, I drew on the sonnet’s equally useful purpose of being a handy vehicle for the lover’s complaint.

CH: Do you have a favorite sonnet writer? (Old, new, famous, unheard of, etc.?) What about the Italian and French sonnet writers?

DP: Actually, Gertrude Stein had as great an influence on this sonnet series as Shakespeare or Petrarch. The book’s very structure is a nod to her plays which have been known to mock sequential time. Her work reminded me that a failed love affair can be about repetitive patterns, patterns that can manifest in rhyme schemes that sometimes poke fun at the equally repetitive emotional extremes that come with falling in and out of love. You can also see her impact in “Sonnet IIX or Sonnet VIII” which translates the opening poem “Sonnet 8” into homonymical nonsense that makes its own kind of sense and “Sonnet i” which is indebted to her way of representing states of consciousness with a plainspoken English shorn of any frills.

CH: You are a master of rhyme, making canny use of approximate and minor accent rhyme. Do you use rhyme in other poems, non-sonnets?

DP: I’ve tried my hand at the villanelle and the rondeau but never clicked with those formats quite the way I did with the sonnet. But even with those very differently pre-set structures, I enjoyed how an impending end rhyme would act like a ring of keys presenting possible word choices to open different doors. Then I had to figure out whether the room was worth entering or whether the door should be re-shut.

CH: About the numbers in the titles…

DP: The numbered title is such a common practice with sonnets that it’s become a cliche, perhaps as organic to the form as three quatrains and an ending couplet or the use of iambic pentameter. The first sonnet I wrote — the carnivorous “Sonnet 8” — was playing with how “eight” sounds like “ate.” This nudged me to find ways to always have the number within the title comment on the ensuing content. Once I started writing poems inspired by pi, zero, and gazillion, though, I knew that this particular affair was decidedly over.

About the reviewer/interviewer:

Clarinda Harriss is Professor Emerita of English, Towson University. She is director of BrickHouse Books, Inc., and author of 7 poetry collections, most recently INNUMERABLE MOONS, Beignet Books. She is co-editor with Moira Egan of HOT SONNETS, AN ANTHOLOGY (Entasis, 2011).

Recent Comments