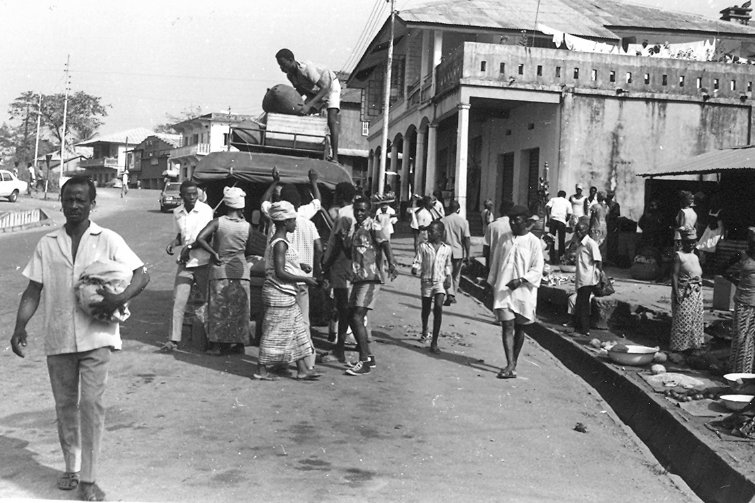

Lorry passengers unloading in downtown Bo, Sierra Leone, Stephen Poleskie photo, 1973

Talking of Travels

by Stephen Poleskie

A

few weeks ago a good friend of mine, who I hadn’t seen in some time, stopped by the house for a chat. He had just gotten back from a trip to Greece, so our conversation began with this country, where I hadn’t been since 1981. My visit then was to the western city of Thessalonica. I was on my way to Belgrade, which was then part of Yugoslavia, when I got caught up in a war in Kosovo. You may have read about this in a previous issue of Ragazine.

After spending some time revisiting Greece, our conversation got around to the most obscure places we had been. I gave my vote to Sierra Leone. As my trip there was back in 1973, and the country has experienced much since then, including a civil war and the Ebola virus, I am sure it has changed a great deal. I couldn’t help wondering what had happened to a young lad named Francis, who had worked as a houseboy for the friend I was visiting, who was living in the then small village of Telu, as a Peace Corps volunteer. Francis would be in his middle fifties by now, if he is still alive.

I had flown to Freetown via Lisbon, Portugal. An incident on the flight, where I drank a glass of Sherry with the captain of the British Caledonian Airways 727 while flying over the Atlantic at 33,000 feet, has also been related in a Ragazine article. I remembered two other curious incidents from that flight. One was our night landing in Bathurst, Gambia, where the runway lights were actually oil lanterns, each one individually manned by a squatting person in a white robe. The lights were extinguished to save fuel when our airplane taxied past and then lit up again when we taxied out. My second memory was of the paramount chief, in a colorful dashiki, who strode proudly onto the airplane followed by his three wives, being doused by a gauntlet of flight attendants wielding spray cans of I don’t know what. The chief kept his head high, with an unfazed look on his face, as the contents of the aerosol cans rained down on him and his women.

The ride in on a bus from the airport in Lungi was also quite an event. It was night, and our luggage was loaded on the top of the bus. Whenever the vehicle made one of its several stops before arriving in central Freetown, everyone got off and stood in the darkness watching that their bags were not taken off by the departing passengers. One of the British Caledonian crew members had clued me in to this custom before the first stop.

When the bus finally got to my hotel, I realized that this was not where I wanted to be, but across the street. There it was. I had never been here before, but I knew the place from Graham Greene’s book The Heart of the Matter. It was The City Hotel, the prototype for the hotel Bedford in Greene’s 1948 novel.

I pushed open The City Hotel’s front door and walked inside. My eyes danced around the lobby. It was just as Graham Greene had described it. I was no longer a university professor traveling on his mid-semester break. I was Major Scobie, British Intelligence MI6, scanning the room for potential spies. A man pushed his way through the beaded curtains that led to the bar and took a position behind the front desk. I asked if there was a room available for the night.

I can’t remember how my friend found me the next day, across the street from where I was supposed to have checked in. That hotel was the place for Peace Corp people and visitors. At the time The City Hotel was mostly for upper-class travelers and foreign business people; as for spies, more about that later. After breakfast we were on our way upcountry.

My friend, who taught English in the village school, lived in a tin-roofed shack, which was one of the finer structures in this isolated community. An outhouse made of bush sticks had been recently erected behind the house especially for my visit. I was told to knock loudly on the rather flimsy door before entering, not because someone else might be inside using it; the local population all frequented the surrounding forest. I was warned that there was a cobra snake that liked to hang around inside. Well, heeding this advice I knocked diligently, until one day I got the notion that maybe a joke was being played on me. I pushed the door open without knocking and there it was; no joke. The reptile sat up and flashed its tongue at me before slithering away. I must admit that this was the first and only time that I had gone eye to eye with a live cobra.

There wasn’t much for me to do during the day while my friend was teaching. I recall walking around the village nodding at people, smiling and saying something I remember as “dyamah bohwa,” which was apparently the Mende equivalent of “Hello, how are you?”

In the evenings we sat around drinking the local brew, palm wine. This was supposed to be the best palm wine around, brewed by a well-regarded man who had a place just outside the village. One day, our palm wine supply exhausted, we trudged off to the wine man’s shack.

The palm wine man was glad to see us. After he had filled the two jugs that we had brought, we sat around chatting and sampling his wares. When we got up to leave the wine man said something in Mende and handed my friend some money. “What was that about?” I asked when we were outside. The reply I got was; “I told him that we are going to Bo tomorrow, so he asked me to pick up a six pack of Heineken’s for him.”

Bo was the nearest place that could be called a city. It was where you went to buy things like beer. Back then the country only sported two brands of the beverage, the local Africa Star and the imported Heineken.

There was only one way to get to Bo; this was by lorry, called a “tap tap.” Back then there were two options: Djelloul’s Nissan and Sheiko’s Toyota. Both arrived at about the same time at the open field next to the winding dirt road that passed for the highway. Which lorry came first was always a surprise. In fact it was rather a race. If Djelloul arrived first and filled up, leaving no passengers, Sheiko would not stop at all but rush on to the next stop. If Djelloul had an empty seat or two he would speed after his competitor, trying to pass him on the way to beat him to the next fares. We made this trip several times so I remember well being jostled about in the back of a converted pickup truck as it raced along the bumpy two lane road, often encountering lions and baboons on the way. The other thing I remember was the local women passengers rushing to cover their normally naked breasts when a white man clambered into the lorry. My friend told me it was something the missionary fathers had taught them to do.

After what seemed like a too short while up country, it was time to return to Freetown. I don’t remember how we got there, but I do remember flying back. There was a small airport in Bo. I recall that we took Francis there with us, as my friend was not going on the airplane. This brings to mind the boy’s comment when he saw an airplane on the ground for the first time: “How close does the great bird come before it can walk on the land?” Maybe he grew up to be a poet?

The airplane was a twin-engine de Havilland model I was not familiar with, probably a modified Dove. Strangely it had fixed pitch propellers and a fixed landing gear, which made it rather dated. However, the oddest thing was that it only had one pilot. No, there wasn’t an empty seat up front. There was only one seat. Apparently the airplane had been designed to be flown by a single pilot. I couldn’t resist asking the pilot what happened if he became incapacitated. His answer was that he flew low enough that if anything catastrophic occurred the airplane would slowly glide down and crash in the jungle. As there were only three people on the eight passenger airplane I chose a seat behind the pilot, ready to take over if I was needed.

Back in Freetown I found a different city than the one I had left. There was talk of a coup. Everyone seemed on edge. One of the government ministers was being tried for ritual murder. He was accused of killing a pregnant village woman and cutting out her fetus. This he allegedly delivered to a juju man who was to use it to create a spell that would guarantee the official’s election to the higher office he was seeking.

My spy story moment came on my last night in Sierra Leone. I was again staying at The City Hotel. As I was walking down the hallway to the WC the door to one of the rooms swung open. A man popped out, saw me and then quickly retreated back in; but not before I had a glance inside. The bed was covered with rows of AK-47 rifles.

The next morning, when I stepped outside to catch the bus to the airport in Lungi, the street seemed strangely deserted. A halftrack with soldiers in it was parked at the corner. When the bus did come it was empty, but I got on. At the next stop there was no one waiting, nor were there any passengers at all the other stops. There were, however, plenty of troops and halftracks scattered about the streets.

The bus arrived at the airport and discharged its only passenger. I walked into the normally teeming terminal to find it empty, except for the people who worked there and what seemed like more than the normal complement of armed guards. I went to the ticket counter and checked in. I was told that my flight, which originated in Monrovia, would be on time, and that I should put my bag on the table marked “Customs” and take a seat. There still were no other passengers about.

I found a place from which I could keep an eye on my bag and sat down. After what seemed like a long time, and still no other passengers had arrived, a large black man wearing a colorful dashiki approached me. He flashed a smile and a badge, saying: “Freetown plainclothes police.”

It had been a tedious day so far; I felt in the need of a joke. “Plainclothes, they look like pretty fancy clothes to me. . . .” I spouted

Anger flashed on the policeman’s face. He obviously hadn’t appreciated my humor. “You think the way we Africans dress is funny white boy . . . you’re coming with me. We will see what is funny.”

To be continued…

About the author:

Stephen Poleskie is an artist and a writer. His artworks are in the collections of numerous museums, including the MoMA, and the Metropolitan Museum, in New York. His writing, fiction, and art criticism has appeared in journals in Australia, Czech Republic, Germany, India, Italy, Mexico, the UK, and the USA, and in four anthologies, including The Book of Love, (W.W. Norton) and been twice nominated for a Pushcart Prize. He has published seven books of fiction and taught at a number of schools, including: The School of Visual Arts, NYC, the University of California, Berkeley, and Cornell University. Poleskie lives in Ithaca, NY, with his wife the novelist Jeanne Mackin. website: www.StephenPoleskie.com.

Stephen Poleskie is an artist and a writer. His artworks are in the collections of numerous museums, including the MoMA, and the Metropolitan Museum, in New York. His writing, fiction, and art criticism has appeared in journals in Australia, Czech Republic, Germany, India, Italy, Mexico, the UK, and the USA, and in four anthologies, including The Book of Love, (W.W. Norton) and been twice nominated for a Pushcart Prize. He has published seven books of fiction and taught at a number of schools, including: The School of Visual Arts, NYC, the University of California, Berkeley, and Cornell University. Poleskie lives in Ithaca, NY, with his wife the novelist Jeanne Mackin. website: www.StephenPoleskie.com.

Recent Comments