Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Save Your Cans/Help Pass the Ammunition” World War II posters from 1940

***

Collecting Tin Cans

by Stephen Poleskie

Contributing Columnist

I don’t suppose that I am the only person who goes to sleep at night wondering if they will wake up to find the world at war. Or perhaps the war will have started by the time you read this article. I will not comment on the quality of the world leaders leading the world during these times, enough is uttered in the daily coffee klatches that pass as news programs nowadays. What used to be an overview of the news is now five or six so called experts sitting around babbling on about the day’s top story, which more often than not was the same top story from yesterday and the day before.

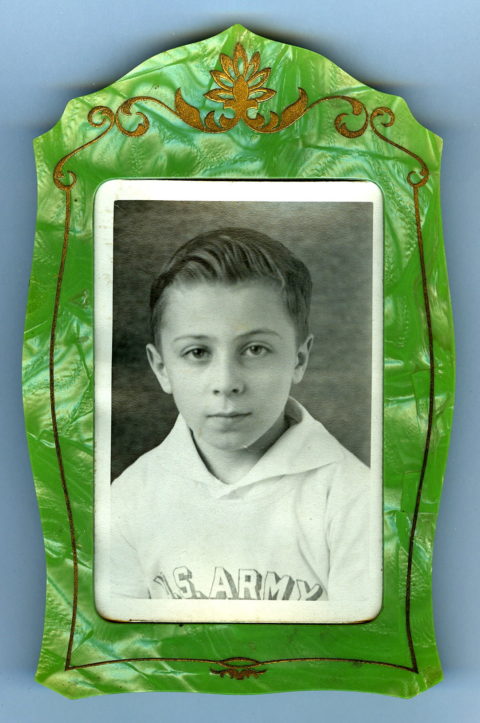

Thinking about what I would do if war starts, my mind returns to what I did during the previous wars that I lived through. The only war that I can say I actively contributed to the war effort was World War Two, although I was only six years old.

Thinking about what I would do if war starts, my mind returns to what I did during the previous wars that I lived through. The only war that I can say I actively contributed to the war effort was World War Two, although I was only six years old.

You ask, and what did a six year old contribute to the help the cause? I collected tin cans. In our school all of the kids in my class did. We were told that the empty cans we brought in would be melted down and made into tanks and guns and airplanes to help our troops beat the Nazis and the Japs.

After my mother finished preparing our meal she would carefully wash out the cans it came in and put them aside for me. Most of what we ate came from cans; Campbells soup, Franco American spaghetti, condensed milk for my sister.

My task was to flatten the cans and then carry them in a sack up the hill to the school. There I turned them in to our teacher, who kept count of how many cans each student had brought in. We were rewarded with patches with stripes on them for our achievements, just like in the military. There was a war on and everyone wanted to be a soldier. We took the stripes home and our mothers sewed them onto our jackets; which we wore proudly, and brought in more cans to get a higher rank. However, I never became more than a private, which made me very unhappy as I brought in every can we had. I was jealous of the other kids who had higher ranks. My mother explained to me the reason that some of the other students were able to bring in more cans was because they came from larger families that ate more food. I wished that we would eat more food so I could get more stripes. There were three of us, but my sister, who was only two years old, hardly ate at all.

The other thing I was jealous of were the little flags with stars on them that people hung in their windows to show someone from the house was away fighting for their country. The flag in our front window had only one blue star; for my father. I passed houses on the way to school that had flags with as many as five stars. Some of these flags had red stars, which meant that a person from the family had been wounded. And my friend Leon’s mother had a flag with a single gold star in her window. Leon’s father had been sent overseas right after training camp and killed in the invasion of France.

We all talked about where our fathers were. Our teacher had two big maps on the wall, one of Europe and one of the Pacific. She would pin name tags on them showing where everyone’s family members were. I was embarrassed because my father was not on the maps, but in the states at a base in Mississippi. He was in the Army Air Force and had been made an instructor for radio operators and not sent overseas. I wondered about this as I recall that all my father knew about our radio was how to turn it on. The story was that, as he had been a school teacher before he was drafted, the army had decided that it would be easier to teach him about radios than it would be to teach someone who knew about radios how to be an instructor. Thinking back on this I wondered why my father had been drafted at all. I recalled my own experience in a later war, where I avoided the draft, for a time, because I was married and a high school teacher. My father had not only been a high school teacher and married with two children and but was also 35 years old. I thought about this years later, when I read an article stating that Germany had been so desperate toward the end of the war that it had begun drafting “old men.” At that time I considered someone of 35 years as being old.

As the war went on, I kept busy collecting tin cans. I regularly went over to my grandmother’s house, which was only three blocks away, and took her cans. On this short journey I even checked out any garbage containers that might have been put out at the curb. After the cans were washed my job was to flatten them, a condition they had to be in before my teacher would accept them. The flattened cans lay proudly in a pile in the corner of the class room until a truck came for them on Fridays. Each room vied for the honor of having the highest pile.

Flattening tin cans was not an easy chore for a skinny little six year old like me. I took my cans into the kitchen and would jump up and down on them until they were sufficiently flat. This annoyed my mother as the activity was beginning to wear a spot in the linoleum where I usually stomped. So when the weather was nice I moved out onto the sidewalk. My mother did not seem too pleased with this idea either as she appeared to be rather embarrassed when neighbors passing by would stop and gawk at me jumping up and down on a can. However, on these occasions I would pause my stomping and explain to the passersby the patriot project I was engaged in. These flattened pieces of metal would eventually be turned in tanks and airplanes.

After what seemed like an eternity time my father was finally allowed to come home on a furlough. Father’s time away had been so extended, in fact, that it had caused my two year old sister to ask, upon seeing him on his first morning home; “Who’s that man in our bathroom?” My mother had replied; “That’s your father; he’s come home from the army to visit us.” Whereupon my sister had pointed at a framed photograph on the wall and said; “That’s not my father, this is.”

Shortly after that my father came into the pantry and found me flattening my tin cans and asked why I was doing it. I explained the whole program to him, which he was not aware of as it had begun after he was away. He scratched his head and smiled; “Now I know what that pile of cans is all about.”

“What pile of cans?” I asked.

My dad explained to me that there was a huge pile of flattened tin cans in one of the fields at his airbase. He said that trucks keep coming at all hours dumping cans and the pile keeps growing. He wondered what they were for. I explained that they were going to be made into tanks and guns and airplanes.

My father was at this base until the end of the war. As they were near his barracks he kept an eye on the growing pile of cans, now as high as a mountain. On the day he left to come home the huge pile of cans was still there, now rusting away. When he told me this I was very disappointed. But this unused pile of cans was in Mississippi, I reasoned, surely the cans that we had saved here in Pennsylvania had been turned into tanks and guns and airplanes; after all, we had won the war.

Years later I learned that back in 1942, when the first scrap drives were organized, and the war was far from over, people of all ages were anxious to do something to help. So campaigns were organized to increase morale. All kinds of things were collected, not just cans, but rubber, kitchen fat, newspapers, rags, and so on. These drives were extremely successful; millions of tons of various materials were gathered. It was only afterward, contemplating these assembled mountains of junk, that those in charge of the war effort asked themselves: What are we going to do with all this unused crap?

So when are we going to begin collecting empty tin cans again? I am waiting for the tweet.

Above Photo: Stephen Age Six (photographer unknown)

About the author:

Stephen Poleskie is an artist and a writer. His artworks are in the collections of numerous museums, including the MoMA, and the Metropolitan Museum, in New York. His writing, fiction, and art criticism has appeared in journals in Australia, Czech Republic, Germany, India, Italy, Mexico, the UK, and the USA, and in four anthologies, including The Book of Love, (W.W. Norton) and been twice nominated for a Pushcart Prize. He has published seven books of fiction and taught at a number of schools, including: The School of Visual Arts, NYC, the University of California, Berkeley, and Cornell University. Poleskie lives in Ithaca, NY, with his wife the novelist Jeanne Mackin. website: www.StephenPoleskie.com.

Recent Comments