The Ghost of Berry Creek

by Richard LeBlond

Contributor

A botanist by trade, I have never lost my love of exploring new habitat and learning new species. So I talked the Forest Service into letting me conduct a small survey on its land in the Great Basin during annual visits from my home in North Carolina. I wanted to learn the plants of a wild mountain stream. In return, the Forest Service would get a reference herbarium: labeled and mounted specimens to confirm or argue with later collections made in the national forest. I had fallen in love with the stark and nearly unpopulated region of east-central Nevada and west-central Utah: Tule Valley, with its landscape from a younger earth; the Snake Range, home of Great Basin National Park and the legendary bristlecone pines of Wheeler Peak; and Ely (“Elee”), the little town still strongly connected to its Old White West history.

The forest is the Humboldt-Toiyabe, the largest national forest in the Lower 48. It is located almost entirely on the rift mountains of Nevada. The mountains themselves are young, about eight million years old. But they are made of ancient rocks. The limestone of Wheeler Peak dates back half a billion years, maybe more. It is a proper place for the bristlecone pines, the oldest living trees on earth. Like most Nevada towns, Ely began as a mining camp in the latter half of the 19th century.

Because of its remoteness, it is a center of civilization; more precisely, it is just about all the civilization there is for a hundred or more miles in every direction. The town hosts the district offices of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and U.S. Forest Service, the two government agencies that oversee most of the unpopulated vastness of east-central Nevada. In recent times, water rights have become a major issue for both agencies. And they became a major issue for me and my little mountain stream survey. It all began when I descended from Success Summit into the valley of Steptoe Creek, in the Schell Creek Range east of Ely. For a short distance, Steptoe Creek is bordered by sloping wet meadows of wildflowers, grasses, sedges, and rushes. I was overcome by a desire to identify them – all of them, as I am now old enough to have lost my fear of the grasses, sedges, and rushes (though to be honest, lichens and mosses still scare the hell out of me). Since I was unfamiliar with almost all of these plants, I would have to collect a sample for study back home. But it is illegal to collect plants on public lands without a permit. I would have to get that permission from the Forest Service office in Ely.

Because of the limited amount of wet meadow habitat along Steptoe Creek, I proposed to the Forest Service that I look for a potential survey site on the other side of Success Summit, at the several creeks in Duck Creek Valley. Almost all of them are paralleled by a dirt road leading to a Forest Service campground. This road increased the probability of impact to stream habitat from runoff and ease of access. But it was ease of access that made these creeks more attractive to my 70-year-old body. (Investigation of environmental impacts by aging biologists will have to wait for another essay.)

I patrolled five creeks one day in early July, looking at water volume, diversity of habitats, and amount of human-caused disturbance. Although I encountered four rattlesnakes during the reconnoiter, I summoned the courage to exclude them from my ranking criteria. I settled on Berry Creek, which had the most water, appeared to have the greatest diversity of habitats, and the least amount of human disturbance. But when I returned in early August to conduct my survey, Berry Creek was gone. Bone dry. Even considering the summer heat and drought, it didn’t seem possible. There had been too much flow in July for it to have dried up completely. Importantly, there was still melting snow in the nearby upper reaches of the watershed. Where the eff had the water gone?

The Forest Service road to the Berry Creek campground crosses the creek a few times. At one crossing I saw a pipe maybe a foot and a half in diameter, parallel to the road and about 30 feet from it. Although airborne by two feet over the now-dry creek bed, the pipe went underground on either side of the crossing. I stopped and walked over to it. As I approached, I was amazed to hear the creek in the distance, about 200 feet away, rushing over rocks and gravels. But as I got closer to the pipe, I realized that’s where the sound was coming from. The creek’s life blood had been entirely captured and enclosed. I had heard the voice of Berry Creek’s ghost. Where was the water being piped to, and why? It didn’t seem a dignified way to treat a national forest creek.

I continued to follow the road, hoping to find the intake mouth of the pipe. As I got closer to the campground, there was still no sign of water. But up ahead I saw something unusual at the summit of a steep forested slope above the creek bed. An enormous cloud of dust was erupting above the trees, like tan smoke. Whatever was causing the dust cloud was moving slowly down the steep slope, beneath the trees. I immediately dismissed the illogical first cause that came to mind: a slowly moving landslide that somehow was not able to dislodge the trees.

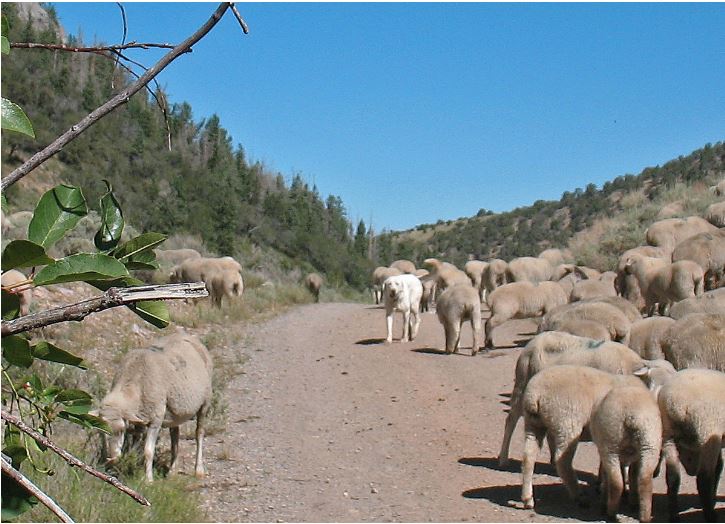

The descending dust cloud reached the confluence of Berry Creek with its north fork just before I got there. And it was another stunning insult. I had witnessed a slow-motion avalanche of sheep – hundreds of them, standing in the creek bed, eating and crapping along its shores. They were tended by two men whom I presumed to be Peruvian based on appearance and the fact that most shepherds in the West today are from Peru.

Among the sheep was a dog similar in color and size to the animals it tended, just a little smaller and whiter. I later determined that it resembled the Basque shepherd dog variety called Iletsua, though its hair was shorter than the Iletsua I saw in photos. Maybe its disguise was too good, and it accidentally had been sheered.

(A man I met at the restaurant counter in Ely’s Hotel Nevada told me that a Basque sheep dog will attack and fight a non-human carnivore to the death. This supports my suspicion that the dog I saw at Berry Creek was a stealth dog, virtually hidden among the sheep, as if to lure a potential attacker. A predator who survived an encounter with such a committed adversary might never again attack any flock of sheep. The meal would have become overpriced.)

As I stepped out of my truck, the dog shyly approached to about 25 feet, then cowered on the ground, writhing in fear. I shudder to think what kind of training produces that kind of behavior towards unfamiliar humans, but it might have saved my life. Although the main fork of Berry Creek was naturally dry above the confluence, there was plenty of water in its north fork. And the sheep were lapping and crapping there. They were also lapping from a pool located at the confluence of the two creek branches. At the downstream end of the pool was the intake for the buried pipe I had seen at the crossing. The pipe traveled two miles downstream from the intake before leaving the national forest on its way to god knows where.

In early July, when I first saw the creek, there had been plenty of water downstream from the collection site. But by August, flow had been reduced to a point where all the water was now being captured by the pipe. Below the intake, the streamside wetland plants had shriveled, or never had a chance to sprout, or had simply disappeared over the years from the altered habitat. And for a distance, the streamside habitat had been thoroughly trampled, eaten, and shat upon. I doubt I could have found a worse place for my little survey. I returned to the Forest Service office in Ely to find out why the water in Berry Creek was being captured by a pipe. I was about to learn how public water is allocated in arid portions of the West.

Much of the water from Duck Creek Valley is piped to the town of McGill in nearby Steptoe Valley. The water has been going there for a long time, ever since the McGill Ranch was bought by the Nevada Consolidated Copper Company at the beginning of the 20th century. The mining company operated a huge open pit copper mine near Ruth, about five miles west of Ely. To process the copper ore, the company built a smelter plant about 12 miles northeast of Ely. To run the plant, the company built a company town, which at first was called Smelter. The town was later renamed for the ranch.

The McGill Ranch was located in Duck Creek Valley, and the mining company bought it to acquire the ranch’s rights to the valley’s water. For the most part, water in the U.S. is publicly-owned. But rights to water in the arid West can be apportioned (permitted) for “beneficial use.” The apportioning is usually done by state governments. The right to use can be sold, transferred, and inherited. Technically, the public owns the water on national forest land in Duck Creek Valley, but the mining company owns the right to use that water “beneficially.” And that right persists as long as the use continues.

Today, the water from Berry Creek and some of the other creeks in Duck Creek Valley is piped to a distribution system that spreads the water over six square miles of smelter tailings. The water irrigates pasture grasses planted as reclamation by Kennecott, the last owner of the smelter, which shut down in 1983. The pasture is grazed by cattle. The project has received the Governor’s Excellence in Reclamation Award, and BLM’s Hardrock Mineral Environmental Award. BLM cited Kennecott’s adoption of “Best Practices to reclaim its sites and minimize environmental degradation.” Apparently, the value of a cow pasture on six square miles of tailings is greater than that of the natural habitats, plants, and animals that once depended on the water in the national forest.

About the author:

Richard LeBlond is a retired biologist living in North Carolina. His essays and photographs have appeared in numerous U.S. and international journals, including Montreal Review, Redux, Compose, New Theory, Lowestoft Chronicle, Trampset, and Still Point Arts Quarterly. His work has been nominated for “Best American Travel Writing” and “Best of the Net.”

Recent Comments