Home on the range for the archaeology students’ first outing was a quonset hut shared by them and the team leaders.

***

Melvin Diggory: Or the Time I

Unearthed a Human Skull

by Jessie Atkin

Contributing Writer

The site was down a dirt road that was half an hour from the closest highway, a highway that was home to nothing more than a Dairy Queen and an Indian-run casino. Our group made the trip in an unmarked white van, sitting three teens to a bench seat. I sat all the way in the back where the bumps in the dirt could throw the top of your head right into the ceiling.

We all wore floppy hats we’d picked up at the mall according to our packing list instructions. Long sleeve button downs that were too old to continue to be part of our school wardrobes covered pasty east coast complexions. I’d packed industrial strength sunscreen because I knew I’d need it.

The New Mexico desert was home to the team of student archaeologists and chaperones.

My sister, my friend Alex, and I were the elders of the students present. We were rising high school freshmen. The other six kids were rising eighth graders. That’s why we sat in the back. We needed the least supervision. We were responsible. Though, when you’re going to work on a real archaeological site you would hope that everyone was responsible.

For a destination labeled a “site” there wasn’t much to see. When the van finally stopped we were treated to a stupendous view of six or seven tents, an outhouse, an outdoor shower, and a Quonset hut (which, if you’ve never seen one, looks like a building made out of a tin can tipped on its side, the lower half buried in the ground). We eleven, students plus chaperones, were introduced to the four real life archaeologists who would be in charge of us for the next week. We girls were also told there was an actual bathroom in the Quonset hut that we were welcome to use.

It was three students to a tent. We dropped off our packs and left our deodorant to melt in the polyester furnaces of our new homes. Then they walked us to the site.

When I say walked, I mean walked. Despite the expanse of New Mexican desert that surrounded us, we were only working on the top of a small and specific hill. A hill we had to walk up from camp. A hill that was especially long that day, as we walked it in the heat of the afternoon. We were warned our hours were going to be early from then on, so that we would hike and work in the less scalding part of any 24 hour period. Truth be told, it always felt pretty scalding.

Like our tents, our work groups were split into threes, the same threes of our sleeping arrangements. One archaeologist to three teenagers. Hannah, and Alex, and I clung to one another and were introduced to Tim. He wore shorts and short sleeves, garments we had all been forbidden to wear in the field. Dark hair encircled a slight bald patch that was already tanned to desert perfection. He gave us a nice smile all the way up to his particularly blue eyes and pointed us to the garbage pit.

The garbage pit was the deepest of the holes we could see. There was a small ladder we used to descend. It was deep enough we were even blessed with a small amount of shade at certain hours when everyone else was forced to crouch behind the truck if the need for cover arose. None of us were ever allowed to ride the truck up to the site.

The garbage pit is exactly what it sounds like, a pit where garbage was thrown, but ancient garbage, so it was much more important and much less smelly than the modern kind. With sharp tipped trowels, sheathed in professional leather shells, we were taught to gently scrape at the pit’s sides before brushing away the excess dust, hoping to reveal small pieces of disposed pottery or animal bones. We learned how to squint at the surrounding brown sand and pick out differences in the feel and the coloring so as not to smash any hidden items by accident. We would call up to Tim, perched above us at the pit’s mouth, when we thought we’d found something. We learned to tell him what we thought it was.

When we weren’t playing in the dirt we were showering under hoses in open-air cubicles, always employing a friend as look out for tarantula wasps that liked to hang around the standing water. There was nothing anyone could do but yell a warning if one headed for an opening while you were lathering up, and luckily no one ever had to decide whether or not to jump buck naked out into the sand or take her chances with the wasp. Sometimes we were a little less adventurous, but no less compelling as we threw a baseball against a backdrop of wild horses wandering past camp behind us. Often we left our polyester prisons for the relief of the great outdoors, sleeping on cots we pitched around a camp fire, and staring at more stars than I had ever seen before, or have seen since. But we also did normal things, like watch movies on an ancient combo television unit with a VHS player. We watched Independence Day, which is a much scarier film in the middle of the desert and, my personal favorite, Raiders of the Lost Ark.

“This is the opposite of archaeology,” Tim told us over the opening scene. Where Indy races booby-traps to grab a golden fertility idol.

It’s like the Internet joke: Indiana Jones, world’s best archaeologist. Destroys every ancient temple he walks into.

But Tim’s statement ignored the fact that Indiana Jones, like the Ark of the Covenant, “represents everything we got into archaeology for in the first place.”

We wanted hidden temples and jewels deposited below the dirt. And that summer we got as close as we could. Our age allowed us to avoid the library research and paperwork where Tim and his associates spent most of their time.

One morning, sweating through our sleeves already, I called up to Tim.

“I’ve got something.”

“Good,” he said. “What does it look like? Can you describe it?”

I brushed deliberately at my find, squinting at the dirt. The item was lighter, larger than the pottery and animal parts we’d been handing up for the past few days.

“I don’t know,” I replied. “I think it looks like teeth.”

I wasn’t talking about tiny teeth. I wasn’t talking about a rodent skull or miniature jawbone. I was talking about teeth, the kind I brushed every morning over the single kitchen sink in the Quonset hut at camp.

Tim switched places with me. I knelt at the garbage pit’s edge and stared down at his practiced motion as he borrowed my brush and trowel. My analysis had been correct. Tim pulled a lower jawbone from the pit’s side and handed it to me. “It’s human,” he told us, as if we couldn’t tell. As if we didn’t know the shape of our own heads, the size of our mouths. The only information that would have excited us more was if he’d said it was alien.

He let us continue our work. The bone didn’t prove anything important. It was an interesting find, but not so unusual that the experts had to take over. Items got disturbed over time. New tribes moved in and items long buried were altered with the earth.

But when my sister Hannah called up, saying she’d uncovered a section of bone, similar in color and size to the jaw I had helped to label and bag, Tim climbed again into the pit. He worked slower this time, his motions even more deliberate than they’d been earlier. I sat with the clipboard of papers and notes and sample bags. Hannah and Tim removed the upper jaw, and most of the rest of the skull, from the pit’s wall.

Tim sent us all up out of the pit and called to a colleague. The two of them, educated and practiced, explored the wall further. They worried we’d dug into an adjacent burial, a planned and honored grave site. There are different rules for burials. None of us visiting students were allowed to work on them, though they had been pointed out to us upon our first trek up the hill. Respect for the dead and buried is required and recorded on archaeological digs. Most bones are reburied after their location and historical notations have been taken down.

At the pit’s mouth, Hannah, Alex, and I watched with the skull at our side. It was 2003 and my Harry Potter obsession was in full swing. The fifth book had just been released and we were all waiting patiently for the third movie. I suggested that we name the skull after a deceased character (spoiler alert), Cedric Diggory. Hannah and Alex, while tolerant of my obsessions and my everyday insanity, insisted he looked more like a Melvin. So Melvin Diggory got his name, and watched beside us as the professionals probed for the rest of his remains.

The rest of Melvin was never found. Tim’s theory stood. Over time, with the arrival of new tenants, Melvin’s remains were likely disturbed in some construction, and fell toward our position at the garbage pit.

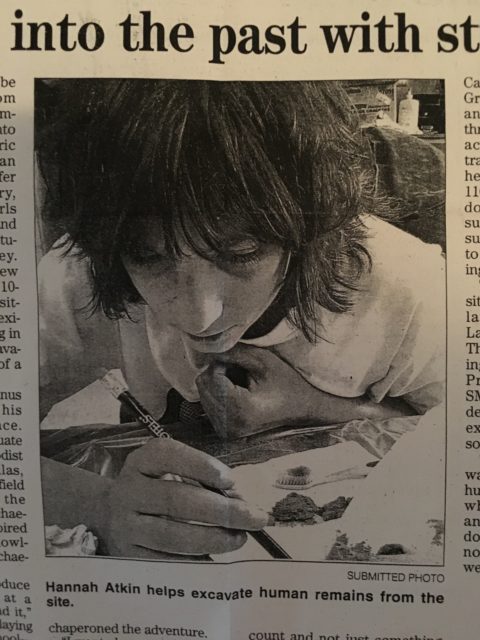

Despite this singular discovery, or perhaps because of it, we were allowed to continue caring for Melvin, and set ourselves to the task of meticulously cleaning the dirt from Melvin’s teeth and skull cavity. A picture of my sister at work in the shade of the Quonset hut made it into the local newspaper upon our return home. But we also met with Tim that evening behind the hut and beyond the showers. The sun was setting behind a fence and the silhouettes of a trio of wild horses. Tim held Melvin and a sprig of sage, which we burned and took turns brushing across the wind. We were respecting Melvin’s spirit that, in our small way, we had disturbed. But we were also acknowledging the disturbance he had suffered before us. His rest had not yet been in peace, and we could only hope in a way, we were doing our part to help him find some.

Two summers later I found myself shriveling under the Greek sun rather than the flare of New Mexico. I stood on the island of Delos, the birthplace of Artemis and Apollo, another set of twins. The island’s ruins rose above the ground rather than below it. There were no walls to chase, (an act that consisted of finding the tops of buildings, their roofs long deteriorated and consumed by surrounding sand, and sweeping along the ground until you found a corner and another wall). There was no need to dig into ancient garbage pits because everything Hannah and Alex and I had been so excited to find, pieces of pottery, lay strewn about the paths we were instructed to walk as tourists.

Perhaps archaeology is not like Indiana Jones, but neither is it always like New Mexico. In America there are funds to study the history of small American Indian settlements in the Southwest. In Greece there is not enough money to pick up the history that lies out on the road in front of you. There was more heat on Delos, but far fewer stars. History seems to matter more the less of it there is. It is why, despite the joy I found in pottery in the middle of a desert, Melvin Diggory stands out above all. We did not unearth as much pottery as I stepped on in Greece, and we only found one human. We had the time and the energy and the enthusiasm to put into his care. What a difference time and money can make. And, what a difference a few kids can make. What we would have given to dig on Delos. What we would have done for the promise of adventure that no one seems willing to fund.

About the author:

Jessie Atkin learned to read later than most, but with the first Harry Potter an obsession was born. Jessie’s now an author and playwright. She has had work published by The YA Review Network, The Grief Diaries, and the Rumpus. She received her MFA in Creative Writing from American University.

Jessie Atkin learned to read later than most, but with the first Harry Potter an obsession was born. Jessie’s now an author and playwright. She has had work published by The YA Review Network, The Grief Diaries, and the Rumpus. She received her MFA in Creative Writing from American University.

Recent Comments